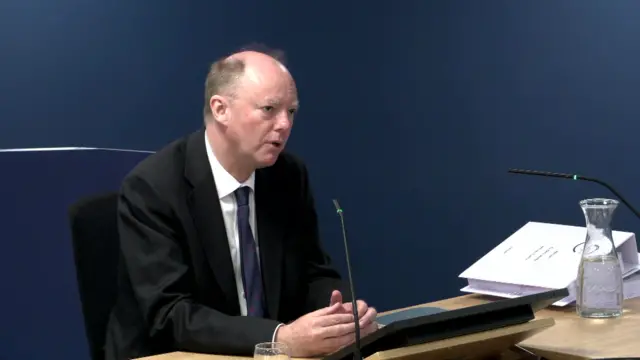

Between emergencies, you have to kind of elbow your way in - Whittypublished at 14:19 BST 22 June 2023

Laura Foster

Laura Foster

Health correspondent, reporting from the inquiry

Some interesting insight from Whitty just now into how scientists and the UK Government have interacted over the years.

“In an emergency, everyone is clamouring for scientific advice. They are desperate to get scientists in the room.

“Between emergencies, you have to kind of elbow your way in.”

Remember Whitty has been in his position as chief medical officer for England since 2019 but prior to this has held multiple scientific advisor roles in government.

These include interim government chief scientific adviser from 2017 – 2018, chief scientific adviser for the department of health and social care between 2016 and 2021 and chief scientific adviser at the Department for International Development (DFID).

He says that within government there’s a lack of understanding of science between emergencies and feels this is “a big risk”.