How to stage the Olympics on a shoestring

- Published

Archive: 1948 Olympic Town in Richmond Park

When London last staged the Olympics in 1948, money was so tight, athletes slept in military huts and leftover food went to local hospitals. Tuesday marks two years to the day until the 2012 Games - what lessons can be learned?

There was no showpiece stadium or aquatic centre, no sleek athletes' village smelling of fresh paint and new upholstery.

London's 1948 Olympics instead had to make do and mend, just as the country had done during World War II - was still doing, in fact, as food, clothing, construction materials and petrol were rationed. The city was a bomb site, many of its buildings pockmarked or toppled in the Blitz, the rubble simply brushed into piles.

Organised in less than two years and with a budget of £730,000, it was a pared-down and practical affair. By contrast, the 2012 Games is expected to cost £7.267bn.

Medals were made of oxidised silver instead of gold. And because of food rationing, competing countries contributed provisions. "The Dutch sent over 100 tons of fruit and vegetables for all the teams. Denmark gave 160,000 eggs. Czechoslovakia gave 20,000 mineral water bottles," recalled Olympic librarian Sandy Duncan in a documentary on the BBC Archive website.

The temporary boxing ring at Empire Pool

"We let everyone know we couldn't build anything new. We could improve the facilities that existed in London and elsewhere, but we could do no more."

It was the first summer Olympics to be held in 12 years, the last being the 1936 Games in Berlin, used by Hitler for propaganda purposes. The 1940 and 1944 events were cancelled as war ravaged Europe and the Pacific.

Athletics took place at Wembley, then the Empire stadium, a venue already 24 years old. To cater for human, rather than greyhound racers, its track was relaid with cinder shortly before the opening ceremony.

At the nearby Empire Pool, the black-out paint on the windows - which prevented light spilling out during wartime air raids - had to be scraped off before it could stage the aquatic events. Boxers shared the venue, with a ring erected over the water. But the pool was never used again - so much for legacy facilities - and it was eventually concreted over to become Wembley Arena.

With accommodation in short supply due to wartime bombs, male athletes were billeted in private homes and at former military camps such as the Army convalescent centre in Richmond Park.

For the women, space was found in nursing and college dorms. Bed linen and blankets were provided, but athletes had to bring their own towels.

To save money on food and accommodation - on which organisers spent a total of £164,644 - local athletes stayed at home. Star hurdler Maureen Gardener, who won silver, travelled by Tube between her home in Snaresbrook and Wembley stadium. Fellow commuters recognised her, and encouraged her to stretch out across the seats to rest.

Pictorial spreads proved to be a draw

British athletes had to make or buy their own uniforms, although one sponsor provided the men with free Y-fronts, with 600 pairs given out in all.

This item of underwear was a novel sight for many overseas competitors - the Y-front had only been patented in 1935 - and sales boomed, says Janie Hampton, author of The Austerity Olympics: When the Games Came to London in 1948. Another beneficiary was the maker of newfangled Pac-a-macs, as July's heatwave turned into August showers.

The press initially hated the idea of spending so much money on two weeks of sport. But as the nation pulled together, and the participating countries rallied around, the mood changed.

"Newsmen from all over the world wanted to be in on the action," says Ms Hampton. "Women's swimming events were a particularly popular opportunity to woo readers with photographs of scantily clad competitors, that were nonetheless all in good taste."

Screen time

Not only was this the first postwar Games, it was the first covered by British television. The BBC paid 1,000 guineas (£1,050) for the broadcasting rights.

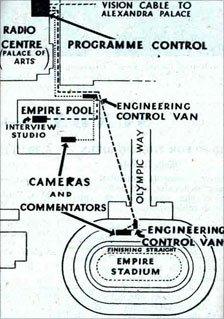

How television units operated at Wembley, from 1948 Radio Times

Outside broadcasts of other news events were put on hold for several weeks to give technicians a chance to test the equipment - much of which was new.

The logistical hurdles were immense, as events took place across south England - shooting in Surrey, sailing at Cowes and Devon's Torbay, cycling at Herne Hill (a south London velodrome used for barrage balloons during the war).

But it was a televisual spectacle few could watch. Not only were TV sets an expensive luxury, only those within a 25-mile radius of the only transmission station - Alexandra Palace in north London - could receive pictures from the Games. Birmingham didn't start transmitting until the following year.

Nonetheless, the Radio Times fretted about unhealthy viewing habits - television was such a novelty, many of its correspondents said they tried to watch all programmes broadcast.

"It is hoped that this habit will not persist during the period of the Olympic Games or viewers will be easily recognised in the streets of London by their pallid appearance!" wrote Ian Orr-Ewing, the BBC's outside broadcast manager, in the magazine.

The opening ceremony itself - "one of the most impressive ceremonies ever televised," said the Radio Times - was a modest affair, with a trumpet fanfare, 21-gun salute and the release of several thousand homing pigeons.

Athletes picnicked while waiting to process into the stadium for the opening ceremony

But the cannons were held up in traffic and only arrived in the nick of time. As for the pigeons, held in trackside cages for several days, half had expired in the heat.

As the athletes picnicked outside, national differences were thrown into stark relief. The British team had extra rations and food parcels from Australia, but the Americans had fresh fruit, meat and bread flown in daily.

"As the procession moved off, we found this picnic area where the Americans had been," recalled Gwen Dance, who worked nearby. "And there we found what they had left. Huge cheeses, huge hams, sweets, cookies, you name it, it was there. For the first time in my life, I became a scavenger."

Adorning the stadium was a sign quoting Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founding father of the modern Olympics: "The important thing is not winning but taking part. The essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well."

1948 Olympic veteran Tommy Godwin tours the 2012 velodrome with the BBC's Sophie Raworth

Never had his words seemed so apt. London had been due to stage the cancelled 1944 Games. So after the war, staging a global event in this battle-scarred but recovering city seemed the perfect way to mark the peace.

One IOC member, Avery Brundage, wanted Los Angeles to stage the Games instead, said Ms Hampton. But the British Olympic Committee - and the government - would not be swayed.

The competing countries accepted it would be an austerity games; that it was important to come together, not stage a lavish spectacle.

On the fields of play, the 1948 Games were also a triumph. Team GB scooped a respectable medal tally - ranking 12th with three golds, 14 silvers and six bronze.

And the event turned a profit of £29,420, on which the organisers then had to pay £9,000 in tax.

- A special programme marking two years until the 2012 Games will screen on BBC One on Tuesday at 1415 BST, also streamed live on the BBC website.