No white elephants in this herd

- Published

A POINT OF VIEW

For centuries, elephants have had symbolic value. Now a charitable art sale is cashing in to help the endangered beasts, says David Cannadine in his Point of View column.

If you happened to be travelling along the Chelsea Embankment in London during the first few days of July, you might have witnessed the extraordinary spectacle of some 250 exotically-decorated and highly-coloured model elephants, each of them about the size of an adolescent animal, and all of them apparently grazing placidly in the extensive grounds of the Royal Hospital.

For two months prior to that they'd been on display at some of the major tourist sites in London, from St Paul's Cathedral to the South Bank, with the aim of raising public awareness of the plight of Asian elephants, whose numbers have been so drastically reduced in recent decades that they are now threatened with extinction.

Many of these models were decorated or donated by famous artists including Marc Quinn, Emma Sargeant and Rebecca Campbell; they were briefly brought together in the grounds of the Royal Chelsea Hospital so that they could be auctioned off; and the proceeds, which were over £4m, have indeed gone towards financing efforts to save Asian elephants.

The trend of creating model animals began with cows

This isn't the first time that such painted fibreglass sculptures of animals have been on display in the streets and squares of London as public art for charitable purposes. The idea seems to have originated with an exhibition of model cows in Zurich in 1998, they later appeared (very appropriately) in Chicago, which was once the greatest meat-market of the world.

In 2000 they reached New York, and I've never forgotten my own amazement on first seeing a large and garishly coloured model cow, reclining uncomfortably on a visibly sagging sofa, in the lobby of Grand Central Station. The cows eventually arrived in London in 2002, and since then they've appeared in Paris, Prague, Rome, Stockholm and Warsaw, and in many other cities around the world.

But public displays of elephants are a more recent phenomenon, beginning in Rotterdam in 2007, then moving on to Antwerp, Amsterdam and Norwich before reaching London this summer, and next year there'll be another such exhibition in Copenhagen.

As every schoolchild is supposed to know, there are significant differences between Asian elephants and African elephants. To begin with, there are still around half a million African elephants in existence; and although this is considerably less than even 30 years ago, there are probably 10 times more of them surviving than there are Asian elephants, which is why they were the objects of this recent campaign and appeal.

But in addition, African elephants are generally larger than Asian elephants, they certainly have much bigger ears, and both the males and the females grow tusks, whereas only the Asian males do so, and their tusks are nothing like as long as those of their African counterparts.

In some ways, these numerical and anatomical differences are less important than another major contrast. For whereas Asian elephants can be domesticated, and given a variety of tasks. African elephants cannot.

The archaeological evidence suggests that Asian elephants were first put to work several thousand years ago, and for many centuries they were primarily used as engines of war. Following the example of the Persians, Alexander the Great deployed elephants in his wars in the Punjab, and they were still being used in such martial capacities in late nineteenth century Indo-China, against the imperial advances of the French.

Elephants were fierce foes and terrifying opponents, for they could literally trample the enemy underfoot, and they also provided a great vantage point from which commanders might survey the battlefield. But the invention of the musket, and more crucially the cannon, eventually rendered them obsolete, as fighting beasts except in the fanciful pages (and the no less fanciful battles) of JRR Tolkien's Lord of the Rings.

Princely power

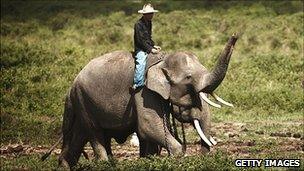

In a more pacific mode, elephants were employed across South Asia and Indo-China in the logging industry, felling and carrying and transporting teak, where they were trained and superintended by elephant boys, or mahouts, who established a lifelong relationship with their animals.

But Asian elephants have not only been used to fight in war and to work in peace. They have also been employed for display - in temples for religious purposes, in circuses for entertainment (though there's less of that than there used to be), and by rulers to overawe their subjects and impress their rivals.

Earlier this year, the Victoria and Albert Museum staged an exhibition entitled Maharajah: the Splendour of India's Royal Courts, and the opening tableau featured a full-sized model of an Asian elephant, magnificently bejewelled, ornamented and caparisoned, and surmounted by a gorgeous, glittering, golden howdah.

During the heyday of the British Raj in India, the rulers of the princely states vied with each other to produce the most magnificent ceremonial and the most magnificent elephants; and the British thought they should compete as well. At the imperial durbar at which King Edward VII was proclaimed Emperor of India, the Viceroy, Lord Curzon, rode on the grandest elephant of all.

But later, when George V visited India in person to be crowned emperor, he made the mistake of riding on a mere horse, which was not at all how an oriental potentate was expected to travel.

Since Indian independence, the grand ceremonials of princely and proconsular power, in which elephants played such a central and starring part, have all but disappeared.

So if you want to catch a sense of how things must once have been in India, you must visit Thailand: Not the Thailand of tsunamis, or of sex-trafficking, or of the recent violent political clashes in downtown Bangkok, but the Thailand of which the elephant is the official national symbol; the Thailand where, every year since 1998, there's been a National Elephant Day; and the Thailand where the most prized and venerated of all creatures is the legendary white elephant.

In fact, such albino animals are rarely pure white in colour, but they're regarded as being of especial merit and value, there's a set procedure for granting official "white elephant" status to them, and the Thai king's greatness is customarily measured by the number of white elephants he owns. (In case you're wondering, the present king has 12 of them, which is the largest royal accumulation to date.)

In some ways, then, the expression "white elephant" carries with it in Thailand a very different meaning from that which we associate with it in the West. For it's a term of esteem and appreciation, and this helps explain why in 1861, an earlier Thai monarch established the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant, consisting of six separate grades, which soon became the most frequently-awarded honour in the country, as it remains to this day.

Asian elephants have been used for work for centuries

He was also the sovereign who offered to send some of his elephants to the United States, where he believed they would do a better job than steam engines in opening up the country for settlement. But his offer was politely declined by the American president, who preferred the iron horse and the railroad.

In addition, and more influentially, the monarch employed a western nanny for his children, whose story later became the inspiration for the Rogers and Hammerstein musical, The King and I. But when the film appeared, in 1956, it was widely regarded in Thailand as being disrespectful to the sovereign, and for a time it was banned throughout the country.

In earlier centuries, it was the custom for kings of Thailand to present those rivals whom they wished to overawe with one of their own white elephants. This was allegedly as a token of royal favour and regard, but it was also in practice a way of inflicting lasting damage on them. For as the highest status animal in the Thai kingdom, white elephants required extensive attention; but, since they were also sacred creatures, they couldn't be put to work to pay for their upkeep, and nor could they be given away or killed.

The recipient of this vengeful act of royal generosity was thus confronted with the high costs of looking after the white elephant, and as often as not went broke as a result. Hence, in turn, our own notion that a white elephant is a valuable possession which cannot be disposed of, even though the expense of maintaining it is out of all proportion to its usefulness or worth.

Perhaps this helps explain why most of the 250 elephants that were recently on display and for sale in London were not painted white but in very bright colours.