Can community sentences replace jail?

- Published

With the prison population rising, along with the cost of keeping people locked up, ministers have indicated they want to see fewer people serving short jail terms. But are community sentences a real alternative?

For those visiting the graves of loved ones, it must come as a comfort to see the cemetery being so well looked after.

Grass has been neatly cut, hedges and shrubs trimmed back and the workmen are in the process of laying paving slabs for a path.

Perhaps worth a rare letter to the local press in praise of the council?

But rather than council workers, these are "offenders working in the community" as a notice near the entrance points out.

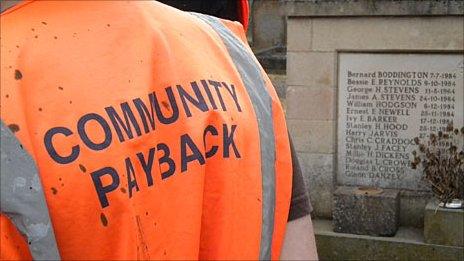

This "community payback" - as emblazoned on the young men's fluorescent jackets - is the latest branding of what used to be called unpaid work - or community service when it was introduced in 1972.

Relief

For Alan Boothroyd, 25, the work in rural Northamptonshire is a welcome alternative to jail.

"Last week we were putting in raised flower beds at a disabled school. It gives me a lot of pride," he says.

His story is similar to many others; left school with poor grades, became a trainee stonemason until the company went bust, "got bored and fell in with the wrong people".

Alan ended up in jail on remand when he didn't turn up for an appointment with a probation officer ahead of being sentenced for two counts of burglary. He was expecting to be sent back to jail but was instead given 200 hours payback and ordered to undertake an education, training and employment course.

"I was relieved. When I was in prison, there was no routine but at least with this you're getting up and going to work," he says.

The course is improving his English and maths so he can apply for a college course in mechanics.

"It gives me time to look for a job so I can provide for myself," he adds.

His is the kind of sentence Ken Clarke appeared to advocate when he declared it was "virtually impossible to do anything productive with offenders on short [prison] sentences" in his first speech as justice secretary., external

In the process, he angered predecessor Michael Howard who - as home secretary in 1993 - declared "prison works".

However, with the prison population at a record 85,000 - nearly double that in Mr Howard's day - and justice about to lose £2bn of its £9bn budget, changes seem inevitable.

It costs more than £50,000 a year on average to keep a petty criminal in prison against £2,800 to administer a community sentence, the government says.

Champions of community punishment suggest they are also more effective, pointing to reoffending rates of around 36%, compared to 60% among those released from short sentences.

The key, they say, is that they are not limited to having offenders paint railings or tidy parks.

Today's magistrates have powers to impose punishments which aim to do any combination of punish people, change behaviour, control offending and help with personal problems.

Punishments can include a curfew, compulsory drug rehabilitation or education, and group work to discuss behaviour at an "attendance centre".

Public scepticism

Through the modern incarnation of the first probation programmes of the 19th Century, officers can challenge offenders to recognise the consequences of their actions, or tackle issues such as anger management, domestic violence and drink driving.

The Howard League for Penal Reform argues that because petty criminals are more likely to be affected by homelessness, unemployment, substance abuse and mental health issues, community punishment is more effective than a short jail term, which does not allow time for behavioural intervention.

So, if they work so well, why are community sentences not already the norm for less serious crimes?

Perhaps the justice secretary best sums it up: "Successive governments have tried to make community penalties more tough and effective. The public are still not convinced they are as effective as prison."

Sceptics include the Magistrates Association, which points to a 2008 National Audit Office report suggesting some probation officers sometimes overlook "unacceptable" excuses, external for offenders not turning up.

On average, three no-shows were accepted in the first six-months of orders. One in five were due to "sleeping in" or illnesses without a sick note, despite rules restricting absence to causes such as medical appointments, work or meetings with other agencies.

Even then, the association's chairman John Thornhill argues that 80% of petty offenders only end up in prison because they have failed to comply with orders "two, three or four times".

"We have no choice as magistrates but to send them to custody."

Unpaid work is most often associated with community punishment

He is calling for community sentences to be made tougher and the association has backed pilot schemes in six areas offering intensive seven-day-a-week supervision.

Official figures show about 65%, external of the 11,000 or so community orders handed down in England and Wales each month are completed in full or finish early because the offender makes good progress.

Offenders fail to finish the remaining 35%, often because they simply do not turn up, breach curfews, or are convicted of another offence.

Neil Cowen, crime researcher for social affairs think-tank Civitas, says reoffending statistics are skewed because those on short sentences have usually already breached community orders and so are the most likely to continue offending.

"Short sentences don't tend to do much other than give the community a brief respite but the incapacitation effect is quite important," he says.

While they may cost more than community punishment, the cost to society of keeping that offender in the community - in terms of effects on people, businesses and public services - may actually be greater, adds Mr Cowen.

'No deterrent'

A report by independent charity the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies last year, based on interviews with 25 probation officers, summed up the view of many critics.

It quoted one respondent as saying offenders placed on community orders left court "laughing their heads off", while another officer complained that people who failed to comply were not dealt with strongly enough:

"You go to court for a breach and you don't get sent to prison, you go back on the van next week and all your mates tell everybody else about it. It doesn't have the deterrent effect that it's meant to have."

But the centre's director Richard Garside says community sentences do have their strengths.

"One of the biggest problems for people coming out of prison is that they have lost jobs, their house, lost touch with their family. That's a terribly bad place to start when you're trying to rebuild your life."

Working people can now do their community payback at weekends, so they do not have to lose their job.

But Mr Garside says you cannot simply displace people from prison into community service, given the number of people serving in both has been rising.

The centre recently reported that prisons spending rose, external from £2.87bn in 2003/4 to nearly £4bn in 2008/9. But the number of people under probation supervision also increased by 38.7% in the decade to 2009, with spending rising from £665m to £1bn in the seven years to 2007/8.

"The general trend has been to toughen up conditions placed on community service which can have the paradoxical effect of increasing the chances of the orders being breached," Mr Garside points out.

Back in Northamptonshire, placement officer Ranjit Samat operates a "zero tolerance" approach with issues like swearing or using a mobile phone. Transgress and you are sent off-site, which constitutes a breach.

He says there are always a few problems - often those with drug or alcohol issues do not want to take part - but that nine-out-of-10 respond well.

His seven-strong group exchange banter like any other work team, among them the owner of a small construction company who is directing work.

Stepping back after laying a slab, Richard Hawkes, 22, vows to "learn from his mistakes" which saw him in court for hitting someone with a bottle - his first time in trouble.

"I thought I was looking at prison. It was very scary. But I've enjoyed this work and now I want to keep my head down."

The government has enlisted community groups, the private and voluntary sectors to help shape reform and repeated Mr Clarke's suggestion of paying such groups to reduce offending.

Whatever the results of this consultation, it seems community punishment will play an increasing role.

- Published22 July 2010

- Published21 June 2010

- Published30 June 2010

- Published30 June 2010