The big cheese

- Published

As tens of thousands are expected to flock to a major cheese fair, why have Britons started taking this once-humble foodstuff very seriously indeed?

Everywhere you look, one yellowing, waxy sight dominates the landscape: cheese, and tonnes of it.

In a marquee the size of one and a half football fields, all you can see - and smell - is great pungent hunks of the stuff: Brie, Wensleydale, Cheddar, Stilton, Yarg.

Slowly, deliberately, teams of stern, white-coated judges purposefully make their way through this array - fingering, sniffing, and finally tasting each sample.

Behind the stalls surrounding this main arena, barely suppressing their anxiety, the producers who have crafted the produce look on.

In sombre, reverent tones, their talk is of curds, creameries and coagulation. Here, cheese is a very serious business indeed.

Welcome to Nantwich, Cheshire, home to the Palme D'Or of the cheese world, the Oscars of the dairy industry: the International Cheese Awards.

The judges are looking for consistency, texture and balance in a champion cheese

More than 3,000 entrants from 24 countries have submitted their wares for inspection.

But the surge of enthusiasm among the British public for a product forged almost literally in their own back yards has given the event - now in its 113th year - a renewed significance. On Wednesday, when the marquee is opened to the general public, some 30,000 visitors are expected to attend.

It is an astonishing level of interest in a specialist trade fair and a product that, barely a generation ago, would have been regarded by most as a prosaic sandwich filling - associated as much with Kraft slices and rubbery supermarket own-brand fare than haute cuisine.

But now, following a rise in culinary expectations and with gastronomic language having filtered through to ordinary supermarket shoppers via TV chefs, it appears that the British are prepared to approach this staple artisan dish with the reverence of, say, the French or the Italians.

Just as real ale went from being a neglected, minority interest to a mainstream enthusiasm within barely 30 years, so too are the dairy equivalents of microbreweries benefiting from the boom in farmers' markets.

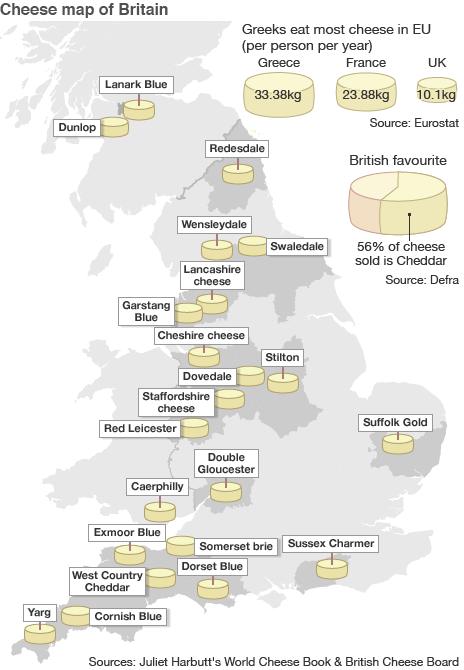

The UK, after all, is a major cheese-producing country: 700 varieties are produced within these shores, 14 of which are subject to protected designation of origin in the same manner as champagne or Parma ham.

As a consumer of the product, however, the country remains resolutely mid-table in European terms. According to the British Cheese Board (BCB), the British consume some 600,000 tonnes of the product (excluding fromage frais and cottage cheese) each year, or 10kg per person - but this is still only about half as much as consumers in Germany, France, Italy and Greece manage to put away.

Wensleydale, West Country Cheddar, Somerset Brie and Cornish Blue

The industry is confident that the UK market can catch up. But right now, most producers are focused chiefly on how their own cheeses fare in the awards' 320 categories. They eye each other nervously in the manner of international rock stars at the Grammys ceremony.

As the clock ticks down and the judges continue their ruminations, Ian Coggin, 51, sales director of Dewlay, a Lancashire-based cheese firm, admits he is nervous.

"We were Supreme Champion here in 1990," he recalls, wistfully. "It's a generation ago, but I'll always remember it because - well, it's a lifetime achievement, really.

His eyes narrow. "This competition is huge. To us, to win a medal at Nantwich, it's absolutely massive."

Cheese enthusiasts hope the product can take off in the same way as real ale

Liz Sutton, 52, has been coming here for 25 years representing goat's cheese dairy Delamere in Knutsford, Cheshire. She acknowledges that few casual cheese fans will engage with the awards on quite the same level as her fellow professionals, but is adamant that the many rewards of cheese appreciation are open to everyone.

"I don't think people outside the industry really understand why we get so excited," she laughs.

"But you can tell from walking round here today the passion that goes into cheese. Everybody's got their favourite and there's so much variety. I defy anybody not to love cheese."

One of those tasked with evaluating the samples on display is Sean Wilson, who may be better known to most for having played Gail Tilsley's former husband Martin Platt in Coronation Street. Wilson is a food enthusiast who produces three farmhouse varieties at Saddleworth Cheeses in Lancashire.

He talks airily and authoritatively about the crucial components that a judge looks for in a winning cheese - consistency, good texture, an even balance of flavours. But while Wilson acknowledges that few high street consumers will apply quite this level of connoisseurship on their weekly shop, he believes that more and more are taking the product with the seriousness it deserves.

"There are, for me, two different styles of cheeses - the cheese that you just pick up wrapped in plastic at your supermarket, but you've also got the people who will choose a proper farmhouse cheese at a farmer's market or a deli," he says.

"And the style that buys the proper cheese, the movement's definitely growing. The British cheese counter is quite a big counter now, wherever you go. The public is starting to appreciate it."

So can Wilson's proper cheese follow the example of real ale - neglected and taken for granted a generation ago, but now boasting an array of hand pumps and self-proclaimed experts in pubs across the country?

Nigel White, secretary of the BCB, believes it is already there. To him, the surge of interest in more challenging varieties is a side-effect of broader social change.

"Over the last 30 years, there has been a revolution in cheese-making in this country," he insists. "In the 70s, we had a period where a lot of the cheese out there was very bland.

"But consumers have changed their palates - they've become more adventurous because we travel more. They're taking food more seriously and they're looking for more interesting flavours."

The tens of thousands who are flocking into this marquee, at the very least, would concur.

And if they, too, go forth and evangelise for the wonders of cheese, perhaps this very British culinary revolution will continue.