The Wellington bomber plane built in a day

- Published

In the midst of World War II, workers at a Welsh aircraft factory gave up their weekend off to build a Wellington bomber from scratch in just 24 hours. Why? To set a new world record.

With the country under attack and the war effort in full swing, worrying about world records might have seemed like a strange thing to do.

But after months of nightly bombing raids by the Luftwaffe, the Ministry of War was keen to show the world - friend and foe - that Britain could dish it out as well as take it.

And so, in collaboration with the RAF, the ministry issued a challenge to one of the factories churning out planes for Bomber Command - to build an operational Wellington bomber in record-breaking time, faster than the existing record of 48 hours set in California.

"It might seem odd, but the whole point of wartime aircraft production is speed," says historian James Holland.

"It's sticking two fingers up at Nazi Germany and at the rest of the world. Our image of Germany is that they were all Teutonic efficiency and we were a bit amateurish, but it was the opposite.

"If you're breaking records in the middle of a war, it shows confidence, and it gives the workers involved a boost."

It was wartime propaganda, to bolster spirits at home and put the wind up the enemy. Such a stunt demonstrated the efficiency of Britain's factories and the unbowed spirit of its people.

And it was a muscular demonstration of Winston Churchill's one policy - to defeat Germany, whatever the cost. In September 1940, he wrote "the bombers alone will provide the means for victory". At his order, vast resources poured into Bomber Command.

Although the exact date of the stunt is lost, National Archives records suggest it was staged in early summer 1943 - about the time British bombers flattened Hamburg in attacks that dwarfed the Blitz - and filmed for a Ministry of Information newsreel, external.

"Everybody had someone in the forces, so it was worth fighting for to see them home again," recalls Eileen Lindfield, who took part in the stunt at Broughton factory in north Wales.

At its peak the factory, run by Vickers Armstrong for the Ministry of Aircraft Production, was churning out 28 Wellington bombers a week. Today, it makes the giant wings of the Airbus A380.

That the Americans held the existing record was also significant. Britain was keen to impress its ally, but to beat their time would be one in the eye for coming late to the fight against Hitler. The narrator chosen for the newsreel was an officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force - a deliberate choice of North American accent.

The easily assembled Wellington was perfect for the stunt. Its aluminium frame slotted together like Meccano, with a skin of varnished Irish linen.

It was a mainstay of RAF Bomber Command and Coastal Command during WWII, used to protect retreating troops at Dunkirk and involved in bombing Berlin on 25 August 1940 - the raid which so enraged Hitler, he ordered the Blitz.

And so, one Saturday morning in 1943, Broughton's workers gave up their weekend to assemble Wellington bomber LN514 from scratch and against the clock. Many were women, or men too young, too old or too infirm to join the armed forces.

(Article continues below graphic)

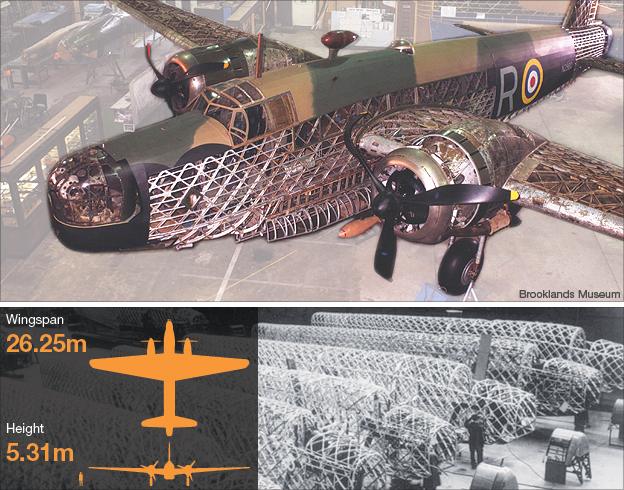

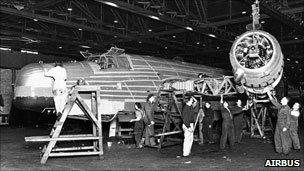

A restored Wellington bomber, showing its geodetic skeleton, and below, under construction in WWII

Of the 6,000 people working 12-hour shifts on Broughton's wartime production lines, more than half were women, drafted in to fill places vacated by men sent to the front lines.

At work on a Wellington at Broughton

Some had been dressmakers. Others nurses, maids, photographic technicians. They stitched its linen carapace, drove the roof cranes that shifted wings and tail fins into position, and installed its electrics.

"Women were absolutely vital - first of all to the war effort as a whole, and to aircraft production," says historian Sir Max Hastings, author of the book Bomber Command. "They were very good at what they did. Britain mobilised women more efficiently than any other wartime nation, except perhaps the Russians."

Betty Weaver was conscripted from the local co-operative store. "I didn't know one end of a screwdriver from another but I got there. I do now. For the first three weeks I didn't sleep, then it all slotted into place."

She, too, worked on Wellington LN514 that weekend. The aim was to complete it in 30 hours, with a pilot on hand to take it up Sunday afternoon.

Throughout the day, workers swarmed to slot together its body, to assemble the engine, to tightly sew its fabric shell - eight stitches to the inch, or the wind could get it and rip the seams open.

By 8.23pm, soon after the night shift arrived, it was time to fit the propellers to the wings. The plane was coming together so fast, workers began laying bets on whether they'd beat their target.

Two hours later, the landing wheels were installed, each one four and a half feet high and weighing 300lbs.

By 3.20am, the plane left the production line, and began a round of inspections and engine tests. At 6.15am - 21 hours and 15 minutes since work started - the engines fired up for final tests, and finishing touches were made to the stitching. And at 8.50am, 10 minutes short of the 24-hour mark, it was ready for take-off.

Work had progressed so fast the pilot had to be awoken from his slumber for its maiden flight. "I hope to God they haven't missed anything," he muttered.

"The record? Yes, they broke it, those workers," remarked the newsreel's narrator. "They said they'd build a bomber in their spare time in 30 hours. Its wheels lifted from the ground in exactly 24 hours and 48 minutes."

That evening, Wellington LN514 was flown to its operational base, ready for duty. And Broughton's workers set to work making another, and another, and another...