Could glasses soon be history?

- Published

Scientists have identified a gene that causes short-sightedness, a discovery which paves the way for treatment to prevent one of the world's most common eye disorders. So could this mean the end of spectacles?

A pair of glasses used to come with its own brand of humiliation in the classroom.

"Four-eyes", "Specky-git" and "Goggles" were some of the names that rang out in the playground and scarred many a childhood.

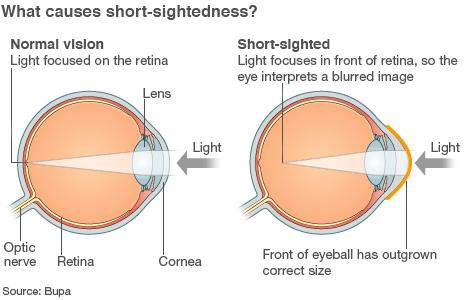

Short-sightedness, or myopia, which makes distant objects appear blurred, often begins in childhood, and it appears to be growing in the UK - now affecting about one in three British adults. But a scientific breakthrough announced this week could start to reduce that number within a decade.

Scientists based in London have identified a gene that causes myopia and are confident that drugs could be developed to halt the distorted growth of the eye that brings about the condition. In about 10 years, shortsightedness could be cured through eye drops, says Dr Chris Hammond, who led the research at King's College London.

"We've known for many years that the most important risk factor to short-sightedness as you get older is family history," he says.

"If one parent is shortsighted then you have a significantly increased risk of being shortsighted, and if you have two shortsighted parents, then you have an even greater risk. But until now, we hadn't identified any genes responsible for that susceptibility."

In a 12-year study which looked at 4,000 twins, the researchers at KCL's Department of Twin Research identified the RASGRF1 gene as one which had variations shared by people with myopia. A separate study in the Netherlands has found a second gene which also governs short sight, and Dr Hammond believes multiple genes are probably responsible.

"It's like being dealt a hand of cards and having lots of high cards which decide you will be shortsighted, or low cards which mean not at all, or cards from the middle which mean you may or may not be.

"So it's not THE myopic gene we've found but it's certainly an important step on the path to understanding how the eye does become shortsighted."

Short sight comes about because the eye ball grows too big and fails to focus light properly. Most children are born long sighted (they can see distant objects but not ones that close by) but the eye continues to grow until it reaches the correct size. In children or young adults that develop short sight, the eye ball keeps growing.

Dr Hammond believes eye drops or tablets given to children or adolescents could block the genetic pathways sending these signals to keep growing, although there would need to be rigorous testing to explore possible side effects.

The thought of a spectacles-free future is fascinating, and would benefit some societies even more than others. While myopia is genetically determined, it is far more likely to be triggered by modern lifestyles, says Dr Hammond.

He believes it is more common in the UK than it was because of the time spent indoors or looking at computer screens.

"Lack of outdoor activity is a risk, as well as lots of close work and being in an urbanised society. So there are general susceptibilities but a number of environmental triggers. So if we had always been outside, looking into the distance, then very few of us would be short-sighted but we live in a more myopic environment these days.

"We know that, for example, it's linked to the number of years of education and an urban, educated society breeds shortsightedness, which has reached epidemic proportions in the Far East."

In Singapore, 80% of adults have myopia, he says, which could be down to the intensive education system.

Successful treatment could override these triggers by tackling the genetic susceptibility but it would never completely do away with the need for glasses, he says.

"I think that certainly the number of people needing glasses could be significantly reduced, yes. But I think there will be some people that have rarer genes that have a big effect and they will still be shortsighted.

"So to say we will eliminate glasses may be overstating it. We're never going to stop myopia in everyone, but we hope to have some impact on the majority."

For many years, people with short sight have had alternatives to glasses, which are impractical for some situations like sport. More than 3 million people in the UK wear contact lenses and a growing number are opting for laser corrective surgery.

Cooler specs

But glasses will always be around, says Karen Sparrow, education adviser at the Association of Optometrists.

"Even if you halted myopia, you wouldn't be able to halt the progression of presbyopia [long-sightedness - an inability to focus on near objects], and the fact that people always need reading glasses later in life. Even laser surgery can't correct that.

"I would doubt whether the usage of glasses is falling because even people who wear contact lenses are not wearing them 24 hours a day. Some find lenses give them dry eyes or they simply can't touch their eyes. And laser surgery is a cosmetic procedure and irreversible, so you have to go into it knowing the limitations."

Ms Sparrow believes spectacle-wearers may not be as desperate to ditch their glasses as is assumed.

Glasses have undergone a change in image in the past 15 years, she says, thanks to the wider choice available and the number of spectacle-wearing celebrities. At the weekend, David Beckham's appearance in Los Angeles wearing glasses was widely covered in the press.

Nana Mouskouri's glasses became her trademark

"They became more cool and more acceptable. Because of the different designs, you're no longer the kid in the corner with the pink or blue NHS glasses. You're the kid in the corner with the latest Bratz specs."

If the gene correction treatment is successful and safe, she says, then some people would be attracted to it, but the popularity of glasses tells its own story about their convenience, with two-thirds of British adults wearing them.

"Glasses will always be around because I can't see everybody opting for new technology. There will always be those more comfortable with what they are used to."

They are not just functional either, they also make a statement, says Catherine Hayward, fashion director at Esquire magazine.

"In the 70s when my sister had to wear glasses at 10 or 11, we were all devastated. She was crying. 'Oh no, being subject to wearing glasses for the rest of your life.' Those ugly National Health ones. The only one in the class wearing them. But now people want to wear them, even if they don't need to.

"A cool pair can make a man look quite handsome, cerebral, a bit of a thinker. But I don't think it's as sexy on a woman because it can hide the make-up and make them look older."

In fashion terms, she says, a pair of glasses is ubiquitous, like a pair of shoes or a belt, so will always be in demand.