The problem with e-fits

- Published

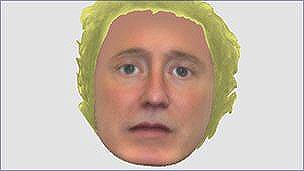

An e-fit of a burglary suspect that looks like he is wearing a lettuce on his head has caused much mirth in the media this week. Police say they had "technical issues" when doing it, but why is a good facial composite still so hard to do?

It has solved countless crimes and is an invaluable resource for the police. But e-fits - now the standard term for such identification technology - still have their limitations, as the appeal for the suspect now widely known as "lettuce man" demonstrates.

The reason for this is straightforward: no technology can ever compensate for the possibility of human error.

Police have had no response to the E-FIT

"If the witness tells you the suspect has green hair, then you just have to go with it," says psychologist Dr Jim Turner of the Open University, an expert in facial perception.

E-fits are produced by an operator working under the direction of a witness. Police have to follow strict guidelines and can only respond in a way which is led by the witness, says Dr Chris Solomon, managing director of VisionMetric Ltd, which produces the E-FIT software used by 90% of police forces in the UK.

Both parties are also required to sign a witness statement to the effect that the operator has not "led" the witness towards a particular likeness. It means the quality of the images cannot be altered by the operator without direction from the witness.

They are often working from memory and sometimes in a distressed state. They also might not have seen the suspect's face for very long or be unable to recall a lot of detail. In the case of the lettuce e-fit, the victim was 85 years old.

'Hostage to ridicule'

"For these reasons, results with e-fits can vary widely," says Dr Solomon. Ultimately, they can only be as good as the witness.

The courts have long recognised the fallibility of onlookers' testimony. In 1976, the Devlin Committee's investigation of identification evidence found that many witnesses overstated their ability to single out the right person.

A recent study involving the Open University, the BBC and Greater Manchester Police (GMP) tested the memories of 10 volunteers by mocking-up "crimes". It found the difference between what people though they'd witnessed and what had actually happened was "staggering".

These are not the only potential problems. Witnesses and the acquaintances of the suspects whom police want to reach will be looking for very different things in an e-fit, says Dr Turner.

"When you don't know someone - as will be the case with most witnesses who end up doing an e-fit - you tend to focus on their external features, such as their hair or the shape of their face," he says.

"But when you do know someone, it's their internal features you notice, that's why you can still recognise someone when they get their hair cut. So there's a disconnect that you have to get over."

Of course e-fit has been designed to mitigate against this. When creating an image, the operator will ask the witness to recall everything they can about the suspect.

Great value

The computer programme will generate a face that may not initially resemble the suspect, but as the shapes, sizes and positions of each feature are altered the picture will - hopefully - offer a more accurate representation.

However, there are still more potential pitfalls. Professor Peter Hancock of Stirling University, who has been involved in the development of evoFIT, an alternative identification programme, believes use of colour is a distraction - and, in the "lettuce head" case, a hostage to ridicule.

Rapist Ross Gleave was caught with the help of EvoFIT

"If you get the hair right, for instance, it doesn't make a lot of difference," he says. "But if you get it wrong, it just looks stupid - as this case shows. That's why evoFIT is in black and white."

With this system, users repeatedly select complete faces from screens of alternatives to allow a composite to "evolve". The approach has the potential to allow construction when a witness has seen the face, but cannot describe it in detail.

What all those involved in the area agree is the relationship between the operator and the witness has to be right for the technique to work.

Bruce Burn, 56, worked as an artist for Northumbria Police in the days before e-fit, but says the principles for coaxing a good image out of a witness are the same.

"The biggest danger is that they defer to you because you're the artist or the police officer," he says. "You need to ensure that they can be hard on you and say 'no, that's rubbish' - otherwise it's not their recollection that you're capturing."

Research suggests that such composites only have an accuracy rate of about 20%. But when you have nothing else to go on they can be good odds.

"Composites images are often used when the police have no other means to attempt to identify a suspect," says Dr Solomon. "As such they perform a very important function and one often not well understood by the public."