Do hard times equal good art?

- Published

Britain's cultural community warns spending cuts will mean a "blitzkrieg" for the arts. But isn't austerity supposed to deliver punk rock and poetry?

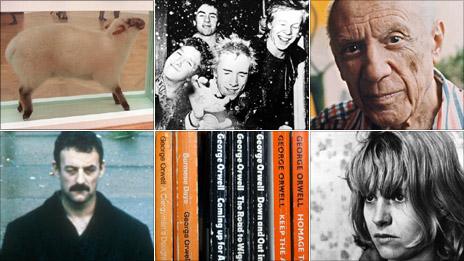

Vincent van Gogh, starving as he slaves over his masterpieces. Johnny Rotten, sneering at the wreckage of 1970s Britain. George Orwell, finding his voice amid the poverty and despair of the Great Depression.

You'd think today's artists would be happier about the prospect of imminent destitution.

A sluggish economy and harsh spending cuts might mean tough times are ahead for most of us, but the romantic narrative of the impoverished poet, musician or painter might lead us to expect that the cultural world could at least anticipate a period of creative fulfilment.

The 1930s gave us Steinbeck and Picasso's greatest work; the turbulent 1970s, recalled for their oil shocks and stagflation, were the backdrop for Hollywood's golden age; the Thatcherite shock therapy of the 1980s generated powerful TV drama like Boys From The Blackstuff, a series which dealt with the effects of unemployment in post-industrial Britain.

But the British cultural community is not anticipating a renaissance to emerge from the forthcoming spending cuts - not least because it is on them that the axe is about to fall hard.

With the Department for Culture, Media and Sport preparing for a departmental budget cut of 25% to 30% and, with the UK Film Council offered up as an early sacrifice, the mood among the nation's arts administrators is apocalyptic.

In a column for the Guardian,, external the director of the Tate, an institution that houses the UK's nation collection of British art, Nicholas Serota, warns of a cultural "blitzkrieg" that will mark "the greatest crisis in the arts and heritage since government funding began in 1940".

A group called Save The Arts has been formed by the likes of David Hockney, Damien Hirst, Antony Gormley and Tracy Emin to campaign against the severity of the DCMS scaling-down.

Their reaction would appear to give the lie to the familiar maxim that hard times are fruitful periods for artists.

And yet, within recent memory, such economic conditions have proved both creatively and financially lucrative for creatives.

The curator Gregor Muir has argued that the slump which 1992's Black Wednesday allowed the Young British Artist scene to flourish in cheap-to-rent, down-at-heel east London - a process which was to make millionaires of its most prominent luminaries and gentrify their postcodes.

Additionally, for those who believe the role of the artist is to speak for the dispossessed, does the hardship that is in store not present obligations as well as opportunities?

The left-wing singer-songwriter Billy Bragg is certainly no supporter of the funding cuts, and he acknowledges that the music industry was already facing deep-seated problems even before the arrival of the credit crunch.

But, weaned on punk rock, and his craft forged during the battles of the 1980s, he does believe that musicians tend to find their voice during periods of crisis.

"As times get hard, it's still the most obvious way to reach out and speak to people," he says.

"And when it starts to sink in how the cuts are going to affect people, we might just see musicians coming to the fore again."

Not everyone is so optimistic. The music journalist Charles Shaar Murray believes there is currently far less potential for a grass-roots movement to emerge than there was in the 1970s, which produced punk rock.

For one thing, he argues that live venues are less accessible to up-and-coming musicians in 2010 than they were in 1977.

For another, he is sceptical that audiences will actually want to hear music that reinforces the gloom and austerity around them.

"When life becomes tougher, entertainment becomes escapist," he says. "Look at Broadway in the 1930s - people want the cultural equivalent of comfort food when they're hard up.

"If any type of music is going to flourish in the years ahead, it'll be the likes of the X Factor."

It's not a prediction to gladden the hearts of most cultural commentators, unless you count Simon Cowell.

But popular music, at least, is largely self-financing in the UK. Those sectors expressing the most anxiety at the prospect of government spending cuts are, naturally enough, those which depend most on public subsidy.

For instance, Arts Council England, which distributes public and lottery funding to cultural bodies, has estimated that out of about 850 organisations on its portfolio, 200 would disappear over a four-year period if cuts of about 30% were made.

Not everyone believes the consequences of this will be entirely negative, however.

Dr Tiffany Jenkins, a cultural sociologist and visiting fellow at the London School of Economics, believes public subsidy has done a great deal to stifle artists, having been often tied to agendas such as increasing community cohesion and forging the regeneration of deprived areas.

The consequence, she argues, has been white elephants such as the National Centre for Popular Music in Sheffield, which was financed with the help of £11m of National Lottery funding and closed its doors after little over a year.

"There's always the problem with funders that they want something for their money - that goes for the government and the Arts Council as much as for private benefactors," Dr Jenkins adds.

"If nothing else, the cuts can teach us that the state isn't the only way."

It is not, however, a perspective that is shared by most in the cultural community. Charlotte Higgins, chief arts writer of the Guardian, believes suggestions that the world of art and heritage will emerge from the pain ahead leaner and more efficient are wrong-headed and simplistic.

She says even the Glyndebourne opera festival, which does not directly rely on government support, in fact indirectly depends on the state funding orchestras like the London Philharmonic. And, she adds, Glyndebourne and that other exemplar of high art and fiscal independence, the Royal Academy of Arts, depend on high ticket prices.

"What's going to happen is that we're going to wake up and find that orchestras have closed, galleries have shut down and museums are falling into disrepair," she says. "What this will mean is that culture and heritage will become more exclusive because those who are deprived or live in remote areas will find it harder to access them.

"I just don't see how this can be a good thing for the arts. The idea that philanthropists will fill the gap is completely delusional."

For his part, Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt has pledged to do his best to target spending cuts on bureaucracy and protect "front-line services" as much as possible.

If nothing else, a young playwright is at this moment surely flexing his or her fingers over a keyboard, wondering how to turn the Comprehensive Spending Review into a three-act drama.