Five meanings of fair - which is fairest of them all?

- Published

Scrapping child benefit for higher-earners has proved controversial, despite government claims it is "fair"

Prime Minister David Cameron has spoken of the need for a fair approach to cutting the UK's spending deficit. But what exactly is fair?

Coming amid economic turmoil which saw taxpayers bailing out banks blamed for recklessly gambling financial stability for the promise of huge bonuses, it was perhaps inevitable that "fairness" would be a recurring theme of the 2010 UK general election.

Labour based its campaign on the offer of "a future fair for all", while the Lib Dems promised fair taxes, a fair chance, fair future and fair deal on their manifesto cover.

The Conservatives peppered their campaign material with similar references although, with their invitation to join the Big Society, it was a slightly different vision - focusing on everyone doing their fair share.

David Cameron expanded on that theme in his first party conference speech as prime minister. But defining fairness is not as easy as it may sound, as the following examples show:

1. Fairness in the "Big Society"

Mr Cameron called for a "new conversation about what fairness really means".

Fairness means giving people what they deserve, says the prime minister

Facing anger from within his party over the scrapping of child benefit for higher earners, he told delegates that "fairness includes asking those on higher incomes to shoulder more of the burden".

"Yes, fairness means giving money to help the poorest in society; people who are sick, who are vulnerable, the elderly," he said.

"But you can't measure fairness just by how much we spend on welfare."

People should be supported out of poverty, not trapped in dependency, he argued.

Going further, he said: "Taking more money from the man who goes out to work long hours every single day so the family next door can go on living a life on benefits without working, is that fair?

"No. Fairness means giving people what they deserve - and what people deserve can depend on how they behave."

2. Fairness in justice

Striking a balance between fairness for victims of crime and the right to a fair trial is a problem ministers are constantly wrestling with.

Are the scales of justice tipped unfairly?

It was once a pillar of English law that a defendant's previous convictions could not be mentioned during a trial, except under particular circumstances such as where there were stark similarities between past offences and a new allegation.

However, the 2003 Criminal Justice Act allowed for juries to be told of a criminal record in cases where it was "relevant" and showed their "bad character".

At the time, the Bar Council's vice-chairman, Matthias Kelly QC, said ministers faced "upsetting the scales of justice" if they proceeded with the controversial proposal.

"It would seriously prejudice the prospects of a fair trial," he argued.

But former Attorney General Baroness Scotland, then a Home Office minister, heralded the act becoming law in December 2004 by saying: "Trials should be a search for the truth and juries should be trusted with all the relevant evidence available to help them to reach proper and fair decisions."

The Scottish Law Commission is currently considering a similar move.

3. A philosopher's view

Philosopher Mark Vernon says people's view of fairness has changed over time.

"Ancient Greek philosophers talked about fairness in terms of your place in society and fulfilling your roles and responsibilities within the community," he says.

While a notion of fairness works best in such relationships, today's individualistic world makes for "profound tension" in discussions about what is fair.

"It doesn't make much sense to ask whether a footballer's pay is fair, because footballers have a skill and ability that is individual. That's why people pay to see them," he argues.

"On the other hand, it does make sense to ask whether a banker's pay is fair because banking is a community activity. Banking would be impossible without a strong society because bankers make money out of others, and that means fairness must operate."

In modern meritocracies, the market decides people's worth and fairness means little more than "what you can get away with", he says.

4. Fair access to schools

Every year thousands of children are denied a place at their first-choice school, sparking protests about a lack of fairness in admissions policy.

A "fair" method for allocating school places has proved elusive

There are a range of arguments about what is the fairest method of deciding who should go to over-subscribed schools.

One of the most common is to choose those who live nearest the school. However, some argue that it allows wealthy people to "queue-jump" by buying a house nearer the school.

"Fair banding" attempts to counter this by grouping pupils into bands, according to their abilities, and allocating a proportion of places to each - thus potentially taking in pupils from a wider area. However, if a large proportion of the applicants are in the top ability band, the allocation of places can reflect this and again deny the poorest children access to a top school.

Awarding places by lottery has also been tried - with Brighton and Hove operating the first city-wide system. However, because it is used in tandem with catchment areas, researchers have suggested it has made little impact in evening out inequality.

On top of this, traditional practices of prioritising children according to faith, awarding them places at the same schools as siblings or testing for admission to grammar schools continue.

5. Fairness in taxation

On the face of it, asking everyone to contribute exactly the same amount to the tax pot might sound like the fairest system of all.

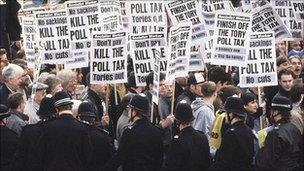

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher tried to introduce such a system with her plan for a flat rate poll tax after winning the 1987 general election.

The Poll Tax. Fair to some but not in the eyes of others

However, asking the rich, middle class and poor to pay the same local tax was denounced as "unfair" and led to mass demonstrations by people from all levels of society, according to journalist and broadcaster Michael Goldfarb, writing for the BBC in August.

The argument was that it failed to take into account people's ability to pay. However, when Labour introduced a 50p top rate of income tax in April, higher earners argued they were being punished despite already contributing the most to the state's coffers.

On the other side of the coin is the amount people take from the state. All Britain's major parties are in favour of universal healthcare but the government now argues that offering child benefit to higher-earners is unfair.

As ministers mull over which budgets to cut and who to tax more, expect the argument over what is fair in terms of sharing burdens and benefits to continue.

- Published5 August 2010

- Published6 October 2010

- Published5 October 2010