It's all in a day's police work

- Published

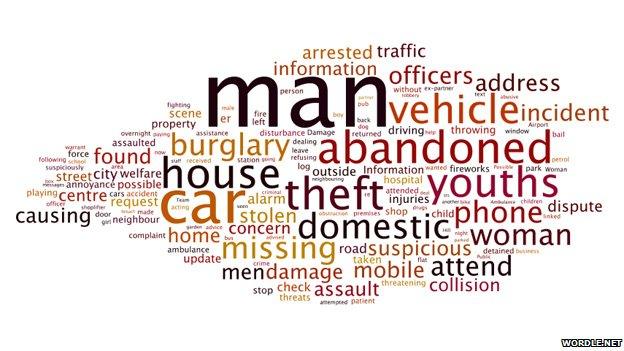

Words like "domestic", "missing" and "youths" are almost as prominent as "theft" and "burglary"

Police in Greater Manchester have completed a 24-hour experiment to record every incident they deal with on Twitter. They hope it will give the public a better idea of the demands made upon them. So what does it reveal about the realities of policing one of the UK's biggest cities?

A policeman's lot is not a happy one, goes the old adage. Nor, to judge by this exercise, does it appear to be a very exciting one.

There was the woman who called 999 because she'd missed the last bus home. A dustbin unaccountably abandoned on the M60 motorway. Loose cows spotted in Atherton.

All in a day's work but not quite the stuff of TV cop dramas.

On Friday morning, Greater Manchester Police wrapped up an experiment designed to raise awareness about the huge weight of demand put upon a modern-day urban police force in Britain.

For 24 hours, between 0500 BST on Thursday and 0500 on Friday, it logged every incident, external that its officers had to deal with on the social networking site Twitter.

The exercise produced 3,205 tweets. But what can we learn from this internet-based approach to publicising police work?

At the top of this page is a word cloud incorporating all the words that appear in the tweets - the bigger the word, the more often it was mentioned.

Banal

Most striking was how banal and mundane many of the calls were. The police are the emergency service of last resort and are expected to respond to an almost infinite range of unfortunate, inexplicable or random events.

Someone from Bolton rang up to complain their builders had turned up two months late. Another person said his television wasn't working and expected the police to do something about it.

But there was also a regular stream of domestic and neighbourhood disputes, often fuelled by alcohol or drugs.

Our word cloud picks out some of the more common incidents and where they occurred.

Unsurprisingly, vehicle crime is very prominent: "Car," "abandoned" and "collision" all appeared frequently on the Twitter feed. And, just as predictably, there are frequent reports of "burglary," "theft" and "damage."

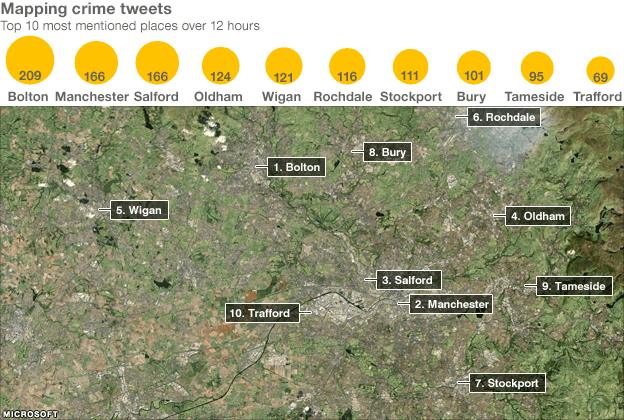

We have left out place names from the cloud but geographical analysis of the tweets reveals that while Manchester is clearly the biggest conurbation in the region, other force divisions also receive high call volumes.

While it appears that more calls refer to the Bolton borough than Manchester, the graphic does not take into account the dozens of references to city suburbs, such as Hulme, Chorlton or Fallowfield.

Some of the more intriguing entries get right to the heart of why the police really wanted to make this information public.

Look at words like "missing", "domestic", "youths", and "dispute". These often come from the calls that take up a disproportionate amount of police time even though they don't always involve an obvious crime.

"A great deal of what we do is dealing with social problems, such as missing children, people with mental health issues and domestic disagreements," says Peter Fahy, the force's chief constable.

Collision course

And frequently it's the same people calling the police time and time again because they can't get satisfaction from the other agencies they turn to like social services, doctors or housing providers.

Of course, with substantial budget cuts anticipated in next week's spending review, it would be naive to think the timing of this very public exercise in self-promotion by Greater Manchester Police was coincidental.

What the force is effectively saying is that policing in the 21st Century is about much more than cops chasing robbers.

Yet in one of her first speeches to senior officers in England and Wales, Home Secretary Theresa May said their mission was simple; to cut crime, no more and no less.

Her remarks echo criticism from some quarters that the police spend too much time acting as social workers and not enough time locking up criminals.

![Thief jumps over railing [posed by model]](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/304/mcs/media/images/49519000/jpg/_49519792_008129238-1.jpg)

The experiment shows modern policing to be about more than "chasing robbers"

She said she was scrapping the previous government's target regime so that forces could concentrate on their core job.

This would appear to put the government on something of a collision course with chief constables like Peter Fahy.

They too want to cut crime but they warn that much of their work inevitably strays into more complex areas, absorbing precious time and resources.

They want their forces' performances to be assessed accordingly, not just by crude measures of whether crime is up or down.

There is even the suggestion that budgets should be allocated jointly to partnerships of police, health and housing agencies to tackle problem communities or families.

The Twitter experiment in Greater Manchester doesn't resolve this issue one way or the other.

What it does is give the public a frank picture of what ordinary police officers really do on a day-to-day basis.

Whether they should do more of some things and less of others is for politicians to decide.

Or perhaps that will be the role of the new, elected Police and Crime Commissioners that the coalition government has pledged to introduce.

Either way, it's a fair bet there won't be many votes for chasing runaway cows through the streets of Atherton.