Is making the Tudors sexy a mistake?

- Published

Elizabeth l is still extremely popular with modern audiences

Religion's rich and bloody history is just as vital to the present as it is the past, says Sarah Dunant in her A Point of View column.

In the summer of 1586, the security forces inside the English government exposed an imminent terrorist threat by a group of Catholic extremists. The plot was nothing less than an attempt to assassinate the queen - a Protestant - and free Mary Stuart - a Catholic - from imprisonment and put her on the throne instead.

In the conspirators' minds their faith made their behaviour completely defensible. The country was being run by a heretic, who by dint of illegitimacy because of her father's divorce (unrecognised by the Pope), was also an impostor to the throne. Success would bring England back to the true faith. Failure would mean their own torture and death, but also their eternal salvation.

Many of the conspirators were young men, well born and well educated, their fantasies of greatness and sacrifice fomented by visits to Catholic countries abroad and the teachings of radical priests, smuggled into England and living underground.

The execution of the guilty took place in two batches. Out of the first seven, the priest John Savage, had to be carried to the scaffold, his body so broken by the rack. Anthony Babington, the young man by whose name the plot came to be known, stood impassively by as his collaborator was hanged once by the neck, then taken down and castrated and disembowelled while still alive.

The history of religion can inspire debate in the classroom

The executions were so grisly and deliberately drawn out, that even the patriotic crowd grew a little uneasy at so much gore. The day after, at the behest of the Queen herself, the sentences were carried out more swiftly and - if it's possible to use the word - humanely.

It's probable that bits, even all, of this story are already known to you. Of course, I have deliberately left out the most famous name, Gloriana herself - the virgin queen Elizabeth I - Tudor.

The Tudors, Elizabeth, her pathologically uxorious father and his six unfortunate wives are, of course, the current superstars of British history. Movies, TV dramas and documentaries draw huge audiences and you can't walk through a book store here - or in America - without being assaulted by a barrage of young women in full Tudor finery, often bodies without any heads (a subtle reminder, no doubt, of the risks of being at court with Henry). Given the mix of lust, palace politics and violence that the dynasty offers, it's perhaps hardly surprising that it's the object of such a cultural feeding frenzy.

It's not the first time. The Victorians had a big crush too. Harrison Ainsworth's novel, The Tower of London, was a best seller during the 1840s and Paul Delaroche created a sensation with his painting of the execution of Lady Jane Grey, a shameless mix of melodrama and sentimentality, with a blindfolded waif Jane feeling her way to the block.

Art of politics

There was another revival during the middle years of the 20th Century. I bet there are women listening now who can already feel a slight flutter in the lower stomach if I say the words Margaret Irwin or Jean Plaidy. Such prolific historical novelists lit up the peaceful, but rather grey, post-war landscape with colourful stories of Tudor and Stuart shenanigans.

At a time where female role models were few and far between, those exotic femmes fatales were the nearest we came to status though, to continue the leit-motif of decapitation, it was a bit dispiriting how many of them literally lost their heads over an undeserving man.

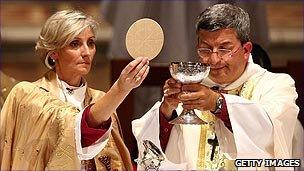

Women priests have made religion a topical subject again

The notable exception, of course, was Elizabeth herself. Here was a character with the longevity, complexity and mystery to ignite a million young imaginations. A woman with the ability to juggle seduction and power in a way that has probably only been matched by Margaret Thatcher (whatever you think of her).

Elizabeth learned the art of politics at a frighteningly early age and even spent part of her adolescence in the Tower of London, under suspicion of treachery. Since this is my last Point of View in this series I'm willing to admit that I wrote my very first novel about that imprisonment. At 14 I identified strongly with Elizabeth. It must have been the sense of incarceration I felt living under the criminal parental curfew of 7pm.

For the record, the novel was mercifully short and excruciatingly bad. I had, I seem to recall, recently discovered the power of the adjective, and every noun had to be preceded by at least four of them.

Like many kids of my age, my obsession with historical romance was eventually pleasurably beaten out of me by great school and university teachers, who having hooked us with the stories, then hit us with the real stuff. In this case the political and cultural complexity of a revolutionary moment.

Extraordinary force

How at a time when belief was a public as well as a private affair, the king of England made a unilateral decision to change the national religion in favour of a new faith, that was running like a forest fire across Europe, with Protestants and Catholics starting to slaughter each with a degree of messianic cruelty that makes one feel sick just thinking about it today.

Until recently, modern Britain hasn't been that interested in religion. The Anglican church that eventually evolved out of religious strife, was in many ways a tolerant affair. Elizabeth herself put it best - she had no desire to make windows into men's souls. The enlightenment, followed by the long, scientific march of Darwin to Dawkins, over time has made secular humanists of many of us, with the stark exception, politically, of Northern Ireland and that of course was as much about un-resolved history as personal faith.

But oh, how much has changed in the last 10 years. Now that polite Anglican church is disembowelling itself over the issues of women bishops and gay priests. Now we are at war against Islamic extremism and increasingly around us belief is a fighting force. From the hard line American right-to-life Christians willing to shoot doctors at abortion clinics to mass slaughter by Islamic terrorists who believe they will get themselves into paradise by murdering others.

How sad then that by and large popular culture is still obsessed with the Tudors as sexy soap opera, rather than as a lens through which we might try to understand some of the extraordinary force of religious conviction and the havoc it can cause in civil society. Of course there are exceptions. CJ Sansom's Tudor detective operates in a city of religious discontent, and Wolfe Hall is a serious study of the reformation, though Hilary Mantel is manifestly more interested in the politics of power than the emotional or spiritual turmoil which comes when people's inner faith is challenged.

Interestingly, those who know history best, are well aware of all of this. Recently, at a meeting of history teachers, a woman working in a school with a large number of practising Muslims told me that when she taught the reformation as a moment when believers found themselves torn between loyalty to their state or their God, the discussion that followed had lit up the whole class.

Agent provocateurs

Suddenly these were no longer stories of funnily-costumed men parading in a distant past, but something hot and vital for the present. And not just for the boys. The history of religion is a place where women can be as passionate and fanatical as any man. Lady Jane Grey may make good copy as a sweet political pawn, but she is fierce about her protestant faith and in the end she embraces her death, repelling all last minute attempts to convert her.

Popular culture is still obsessed with the Tudors

When Simon Schama and Michael Gove sit down together to thrash out a new British history curriculum, I think they would do well to think long and hard about the journey of religion in the formation of our modern, democratic, multicultural Britain. While I dare say that idea would give Richard Dawkins the heebie jeebies, taught well it could surely offer one of the most exciting and penetrating methods of understanding our present through our past.

And along the way history itself will always surprise us. Back to 1586 and those young catholic fanatics. Because, despite all the propaganda, in reality the Babington plot offered no serious threat to the life of Good Queen Bess. Many of Babington's fellow conspirators were actually agent provocateurs infiltrated into the group right from the start in order to monitor, encourage, even facilitate the plot.

It was perfect power politics. Secretary of state Francis Walsingham and others of the Queen's council wanted Mary Stuart dead. As long as she lived there was always an incentive for a Catholic uprising. Elizabeth would not hear of it: the divine right of kings was not something to be put aside lightly.

Walsingham's calculation was that only by exposing Mary's active role in the plot could they persuade the queen to try her cousin for treason. He was right. Elizabeth's signing of Mary's death warrant is the kind of scene where history and fiction were made for each other.

But let's not end by knocking fiction too hard. In the right hands, imagination working its magic on a complex past could surely help to make better historians of us all.