Will these Irish migrants be different from the past?

- Published

Over the years, thousands have crossed the Irish Sea

The Celtic Tiger is in intensive care and young people are rushing for the exits. But how will a new exodus of Irish to Britain compare with previous waves of Irish immigration, asks Tom de Castella?

A couple of days before Ireland's politicians meekly agreed to the EU's financial bailout, a gleaming new terminal opened at Dublin airport.

T2 cost 600m euros but with the economy in deep recession and passenger numbers falling, it is being seen as a monument to Ireland's economic collapse.

Ryanair boss Michael O'Leary arrived at the opening in a hearse dressed in an undertaker's outfit and bearing a coffin, while a taxi driver told the Financial Times: "I suppose they're getting it ready for all the young people trying to emigrate."

Black humour is rife but beneath the joking lies a serious point. Ireland may be on the verge of sending another wave of migrants to foreign shores.

Many young Irish are now reaching for one of these

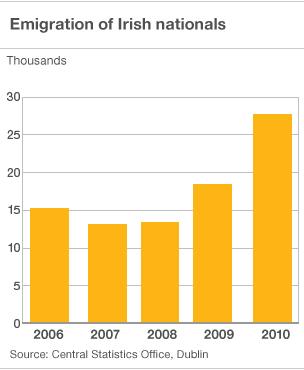

In the year up to April 2010, Irish emigration grew by 40% to 65,000 but almost half of those were Eastern Europeans returning home. The difference now is that the numbers are accelerating and it is the Irish who are leaving, according to the country's Economic and Social Research Institute. In July the research body predicted that 200,000 people would emigrate between 2010 and 2015.

"We've always had a culture of emigration," says Jamie Smyth, social affairs correspondent at the Irish Times, referring to the potato famine of the 1840s in which the Irish population shrank by more than 20% after a million people died and another million emigrated.

With a third of under-25s out of work it is the young who are most likely to leave, with Australia, New Zealand and Canada ahead of the UK as destinations according to last year's figures, says Smyth.

Indeed in the first nine months of 2009, there was only a 7% rise in the number of Irish people registered to work in the UK, hardly a major increase. But he cautions that these figures are a year out of date, and since then the UK economy has begun to recover while Ireland's economic malaise has worsened.

Claire Weir, a 25-year-old graduate, is one of the new arrivals to Britain. At the weekend she packed up her stuff, got a lift to Dublin and took the ferry to Holyhead, en route to a new life in London.

The trained photographer is sleeping on a friend's sofa, looking for part-time work in a supermarket or pub to pay the bills while she finds regular photography work.

"I just want a job, I need a bit of money coming in and can't live on thin air. I don't think I can get that consistency in Ireland."

Part of her photography studies involved taking pictures of the many unfinished property developments that now litter Ireland. She and her friends feel betrayed by a political and business class that has indebted the country for her generation. Now they are voting with their feet.

"If you can get out you do. I come from a rural area in County Meath and there are very few graduates left. Four of my closest friends have gone, the others are either in a relationship or at college so can't leave."

Mary Corcoran, professor of sociology at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, says that the boom years were an exception - for nearly every other decade since the Irish state was founded in 1919, emigration has been part of its economic survival.

Emigration reached its apogee in the 1950s when 50,000 people left a year. The outward trend stopped briefly during the 1970s but returned with a vengeance the following decade when unemployment soared. On average, 35,000 people were leaving the country a year during the 80s.

"That is the decade many are comparing today's situation with. People remember airports at Christmas time packed with emigrants coming home and the farewells in January when they all went back again."

Britain, along with America, was the traditional choice for Irish people seeking a new life. In the 19th Century it was the Irish navvies who built Britain's railways, in the 20th Century they manned the nation's building sites or worked as domestic help, creating Irish ghettos in the big cities.

"When we think of emigration we think of the famine ships or the people who went to Kilburn in the early 70s and drank themselves into an early grave," she says. But the character of emigration has changed. The Irish population today is far better educated with nearly half of 25-34 year-olds having gone on to higher education, the second highest rate in the EU.

Today's immigrants are more likely to be in IT or business than construction. And whereas in the past the US was easy to settle in without papers, today the Patriot Act and tighter checks makes America off limits to most Irish.

So how will the new arrivals to Britain fare? Highly-skilled graduates in areas such as IT will find it relatively easy to get jobs, she believes. But the construction workers who once had easy pickings on British building sites will now be competing against well established East Europeans. On the plus side, whereas it was hard for previous generations to keep in touch with home, the advent of e-mail, Skype and Ryanair has made it much easier for the new wave of immigrants.

The loss of young hurlers has affected village teams

And neither will they face the same hostility as their forebears. Britain was once a byword for prejudice against Irish workers with the notorious "No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish" signs posted on B&B doors. Later, IRA bombings intensified anti-Irish feelings.

But things have changed beyond recognition for the new wave of Irish arrivals in the UK. Not only has the peace process reset the political context and the boom years given the Irish self-confidence, but the activities of radical Islamist groups have created a new scapegoat, she says.

Poet Eavan Boland, who moved to the UK in the 1950s, believes that despite possible tensions over historical baggage, the new wave of immigrants will not face the prejudices expressed in the past.

"The UK is no longer anti-Irish. In those days Ireland was a country that had been disloyal in World War II by staying neutral. It was Catholic. It was only when it became a republic in 1948 - previously it was a Free State - that Irish people could travel in Britain without papers.

"Now we're all European, we have the same passport and are entitled to free movement. Britain was a great partner in the peace process, people went through a lot together.

"And David Cameron made a beautiful speech about Bloody Sunday that was an extremely healing moment. It's come too far, there's too much understanding. I don't think you can reverse that now."

But with some resentment evident on both sides of the Irish Sea about the UK role in the rescue package agreed this week - British taxpayers unhappy and Irish pride rather injured - it remains to be seen where the relationship goes from here.