601 Squadron: Millionaire flying aces of World War II

- Published

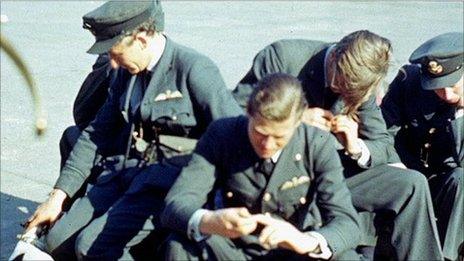

Willie Rhodes-Moorhouse took colour footage of the Millionaires in action

Seventy years after the Battle of Britain, the BBC has retraced the story of a little known amateur RAF squadron formed in a London gentlemen's club and composed of aristocrats and adventurers. But their privileged upbringing did not shield them from the brutal realities of war.

Born into high society in 1914, William Henry Rhodes-Moorhouse was determined to follow a family passion for flying.

His father had built and designed planes and flown in World War I, becoming the first airman to win the Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery in battle.

Flying at just 300ft (91m), William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse volunteered to drop a single bomb on a strategic rail junction near Ypres in the face of intense ground fire. He made it back to British lines, but died of his wounds shortly afterwards.

Amalia refused a screen test to play Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind

Young Willie, his son, was able to fulfil his dream, thanks partly to his school friend George Cleaver, whose family owned a plane. He had his pilot's licence by the age of 17 before leaving Eton.

After extensive travelling, he returned to settle in England where, so family lore records, he "fell head over heels in love" with his wife-to-be, Amalia Demetriadi. A strikingly attractive woman, she was approached in a London restaurant by a talent scout to be screen-tested for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With The Wind. A private person, Amalia declined.

For Amalia and Willie, life must have seemed to be bursting with promise. They were well off and enjoyed invitations to the south of France and skiing trips to St Moritz.

A keen sportsman, Willie was selected for the 1936 British Winter Olympics team, but an accident on the ski jump prevented him from competing. But war was looming and short of funds, the RAF had its eyes on amateur pilots like Willie, George and Amalia's brother Dick. It could not maintain a large peacetime force, but if war came, it would need to mobilise fast.

As early as the mid 1920s, the first Chief of the Air Staff, Lord Trenchard, had come up with the idea of auxiliary squadrons, amateur pilots who could be rapidly recruited and deployed on the outbreak of war.

The first auxiliary squadron, 601, later to be known as the Millionaires' Squadron was, according to legend, created by Lord Grosvenor at the gentlemen's club White's, and restricted to club membership.

Dick Demetriadi, killed in action at 21

Recruitment under Grosvenor involved a trial by alcohol to see if candidates could still behave like gentlemen when drunk. They were apparently required to consume a large port. Gin and tonics would follow back at the club.

Grosvenor wanted officers "of sufficient presence not to be overawed by him and of sufficient means not to be excluded from his favourite pastimes, eating, drinking and Whites," according to the squadron's historian, Tom Moulson.

The squadron attracted the very well-heeled, not just aristocrats but also sportsmen, adventurers and self-made men. There would be no time for petty rules or regulations. But Grosvenor was nonetheless intent on creating an elite fighting unit, as good as any in the RAF.

Under their next commander, Sir Philip Sassoon, the squadron acquired a growing reputation for flamboyance, wearing red socks or red-silk-lined jackets as well as driving fast cars. Wealthy enough to buy cameras, they even took to filming their escapades.

There were other auxiliary squadrons, but none was as exclusive or elitist as 601.

The Millionaires had a reputation for escapades and flouting the rules, says Peter Devitt from the RAF Museum. "But they could not have got away with it without being an efficient and effective fighting unit. They were very serious about their flying and their fighting."

Heavy losses

Days before the German invasion of Poland in 1939, 601 squadron was mobilised. Stationed at RAF Tangmere in West Sussex, by July of the following year, Willie, Dick and George were on the front line.

The German air force, the Luftwaffe, was targeting Allied shipping in the Channel in an attempt to lure the RAF into combat.

On 11 August 1940, in one of the opening skirmishes of the war, 21-year-old Dick Demetriadi was shot down off the Dorset coast.

Willie had lost his best friend, but he also had to break the news to Amalia that her brother would not be coming home.

The following weeks saw intense raids on southern England as the Luftwaffe attempted to destroy the RAF and seize control of the skies to allow an invasion.

Willie and the Millionaires of 601 Squadron were in the thick of the fighting. After heavy losses, the squadron was pulled back to Essex, only to find themselves in the front line again as the Luftwaffe targeted London.

From an initial strength of about 20, they had lost 11 men in action, with others injured or posted to other squadrons.

The replacements were a more mixed crowd. And while many of the Millionaires' traditions survived, they were no longer the band of aristocrats and adventurers who had started the war.

Other squadrons suffered heavy losses too but the RAF pilots were destroying two German planes for every British loss. Willie was responsible for shooting down nine aircraft. On 3 September, he and Amalia were invited to Buckingham Palace where Willie was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

It was to be one of their last times together. Just three days later he was shot down.

Other members of 601 squadron survived the Battle of Britain, including Willie's friend George "Mouse" Cleaver, who shot down seven planes before an eye injury which ended his flying career.

But by the time the Luftwaffe called off its assault and the invasion of Britain was cancelled, the RAF had lost 544 pilots.

Churchill immortalised "the few", but for each man lost, there were wives, parents and sisters left behind, women like Amalia.

It was not fashionable for women like Amalia to go to work and, after the war, she lived within modest means, tending her garden and - like many of the wartime generation who had lived through rationing - recycling everything.

She never remarried, although there were certainly offers, and lived a quiet life until her death in 2003.