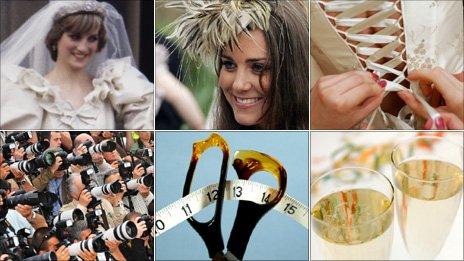

Royal wedding: Can Kate Middleton's dress stay under wraps?

- Published

- comments

With 100 days to go until the royal wedding, Fleet Street is straining to reveal whatever it can about Kate Middleton's dress. How can Buckingham Palace possibly keep the garment hidden until her big day?

There's a secret out there, jealously guarded at the highest level of the British state. A secret that millions are desperate to learn and journalists are scrambling over each other to uncover.

The classified information is not some top-secret intelligence file and it isn't a scientific patent destined to make its inventor wildly rich. It is neither the cure for cancer nor a weapon of mass destruction.

Instead, it is pale-coloured, silky and quite possibly shaped like a meringue. It is a wedding dress, designed for the future Princess Catherine.

As she steps out of her car and makes her way to Westminster Abbey in her final moments as Miss Kate Middleton on 29 April, millions of eyes will be on her gown. Just as with any matrimonial ceremony, the dress will occupy a status within the event's hierarchy only just below that of bride herself.

But the level of fascination in this particular outfit has been amplified and multiplied by the UK monarchy's worldwide fame. Before anyone has even had sight of it, a search for "Kate Middleton wedding dress" throws up more than 300,000 results on Google.

Always alert to public appetites, Fleet Street is deploying the full force of its inquisitorial might to reveal anything it can about the vestment and the identity of its creator.

Indeed, recent paparazzi photographs of Miss Middleton's mother and sister outside a boutique belonging to designer Bruce Oldfield were scrutinised and picked apart for clues, with a depth of analysis usually reserved for videotapes of Osama Bin Laden.

Republicans and those indifferent to both fashion and the House of Windsor soap opera might be utterly perplexed, or indeed disgruntled, that such an apparently trivial matter could be the focus of such intense attention.

But if the experience of royal weddings past is anything to go by, the palace will have to match this scrutiny with a campaign that is SAS-like in its precision and thoroughness to keep the dress under wraps.

Elizabeth Emanuel should know. In 1981 she and her husband David found themselves swamped by press attention when it was revealed they were designing the wedding dress for Princess Diana.

Overnight guards

Ms Emanuel says journalists scoured their rubbish bins, rang up pleading that they would be sacked unless she could give them information, attempted to bribe her staff and rented an office opposite the Emanuels' studio in which a round-the-clock stakeout was maintained.

With, she says, no help or guidance from the palace, she was forced to improvise elaborate security measures.

"We kept the dress in a huge safe," says Ms Emanuel. "They had to hoist it through the window. We had two security guards, Jim and Bert, who would come in and guard it overnight when we went home.

"It was a huge amount of pressure. In case it did leak, we had a spare dress in reserve. It looked very similar but it had slimmer sleeves. Diana was great when she came over to the studio. There was never any feeling it was too stressful for her, but it must have been difficult."

Since the early 1980s Fleet Street may have grown even more ruthless in pursuit of a story, but so too has the palace become cannier. Ms Emanuel says she believes royal courtiers - now far more conscious of the press's rapaciousness in the post-Diana era - will take a much greater hands-on role in keeping the dress hidden.

With so many involved in such an ornate outfit's supply chain, the number of potential insider sources for reporters to cultivate will be considerable.

The prestige of working on such a high-profile design project will, of course, be enough to keep many mouths sealed.

But it is unlikely to be enough for palace officials, who can be expected to insist on all concerned signing confidentiality agreements.

In addition, wedding planner Siobhan Craven-Robins says there are plenty more tricks of the trade, such as making any appointments under pseudonyms, with which to stay one step ahead of the chasing pack.

"The most important thing is not to be tailed by the paparazzi going in for a fitting," she says. "I would imagine the designer would come to her or at the palace rather than do it in their own studios.

"You would think the royals wouldn't have a problem arranging security, after all."

Indeed, the palace has itself become adept at outfoxing the press pack.

Ex-Daily Mirror Royal editor James Whitaker suspects the photographs of the Middletons outside Oldfield's boutique may have been arranged by Clarence House as part of a complicated diversionary strategy.

"I'm sure right now editors are kicking backsides, saying, 'I want to know who the designer is'," he says. "And any self-respecting journalist will be trying to find out.

"But while it's their job to do so, it's the palace's to keep it a secret. I don't know if they are going to be able to, but the dress is always going to be the last thing you find out about."

However, former BBC royal correspondent Jennie Bond suspects that, even in the Britain of 2011, courtiers have an even more powerful weapon at their disposal: old-fashioned deference.

"They'll use honour," she insists. "You are honoured to be creating the royal dress and in return you are expected to keep your trap shut."

Who, after all, wants to be the cad who spoils a bride's big day? As long as that remains a factor, the monarchy is in with a shout of preserving the country's best-embroidered state secret.