Census: 1911 v 2011

- Published

- comments

Infant mortality drove changes to the 1911 census

Next month, the UK will do its most thorough census yet. A century ago, a new expanded form was evidence of a government's thirst for knowledge in their efforts to help a population stricken by poverty, bad nutrition and high infant mortality.

There are many differences between the 1911 and 2011 census.

That of a hundred years ago was able to fit on a single sheet. Today's is likely to be about 30 pages long.

That of 1911 might be regarded as sexist, implying that if there was a husband in the household he would be head of it. And its language on infirmity, asking householders if they were "lunatic, imbecile or feeble-minded", would be unlikely to pass muster with today's disability campaigners.

In 1911, as far as work went, the government just wanted to know occupation, industry, and status. In 2011, the census has 15 nuanced questions on work and employment.

And yet there is a great similarity between the 1911 and 2011 censuses - they both represent expansion in what the authorities want to know about the population.

Censuses have been taken since ancient times, often to calculate taxes, or as an assessment of military strength. In Britain the census started in 1801 and was extended to Ireland 20 years later.

The first censuses in the British Isles were not detailed. Every decade more questions were added, but 1911 represented a sea change.

The government wanted to know more detail about people's work, immigration status, their health and most importantly, their fertility. And it seems for the most part, that people duly obliged.

For the 2011 census, there has already been criticism over the cost and intrusiveness of the questioning. People seem to have overcome these qualms in 1911.

"People were certainly more amenable to these questions in 1911 than in 1841," says historian and broadcaster Nick Barratt.

"There was a lot of government investigation into everyday lives. There wasn't the great hooha you get today about cost and intrusiveness."

That's not to say some people weren't unhappy. The King family of Cheshire seemed to be irked, scrawling in pencil: "Would you like to know what our income is, what each had for breakfast, how long we expect to live and anything else?"

They still filled in the form, including the fact that of 67-year-old Mrs King's 10 children, all had survived. This was crucial information for the government.

"Child mortality had been a hot potato for about 40 years," says Dr Julie-Marie Strange, senior lecturer in Victorian Studies at Manchester University. "From the 1860s there is a real anxiety that people don't value infant life very much and that it is too easy to let infants die."

In the Victorian mindset, immorality was the main suspect. The practice of taking out life insurance on babies was banned, notes Dr Strange, over fears that babies were deliberately being allowed to die.

But by the early 20th Century, infant mortality rates were still stubbornly high.

"General mortality rates went into decline from 1870 - the one exception is infant mortality," says Dr Strange. "The 1911 census allows a thorough statistical understanding. It is allowing mapping of that demographic and death rate.

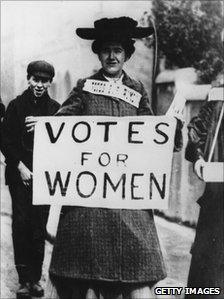

In 1911 the suffragettes tried to ruin the census by staying out all night

"You start to get massive resources ploughed into infant and child welfare. The infant mortality rates start to decline. A lot of it is health visitors improving nutrition - milk depots where mothers can go and get free milk."

Of course, some people would have been wary about people coming into their homes asking about child deaths and marital status.

"That's quite a sensitive issue. Even asking people how long they had been married was a bit contentious," says Debra Chatfield, of findmypast.co.uk, which has the 1911 census online.

"They may have had children conceived before they married. There was a bit of a trend for people to live as if they were Mr and Mrs but they hadn't taken the formal step."

Working-class men were the group most wary of snooping intruders, says Dr Strange.

"There would have been a degree of suspicion. You have very well-spoken people coming to your house and trying to found out things about you."

But the strength of the 1911 census was that it was the first to be filled in by householders rather than by enumerators.

This is what makes it such a goldmine for genealogy buffs. Being able to see an ancestor's actual handwriting is often as pleasing as the information garnered, and there are new nuances for the sharp-eyed to spot.

"You have always had phenomena like postcode inflation. If they write their own address you get a sense of that," says Dan Jones, of ancestry.co.uk, who plan to have the 1911 census online soon.

"Even in how people describe themselves you can get a sense of what they are."

The 1911 census also offers an insight into one of the great political movements of 20th Century Britain, the efforts by suffragettes to get the vote for women.

The activists tried to get women to refuse to fill out the census, organising a mass avoidance session near London's Trafalgar Square, prompting a heartfelt plea from the registrar in the Times.

2011 could see a return of the Jedi census phenomenon

"It furnishes statistics and materials on which are based most of the measures by which the health and happiness of the community are promoted. In the struggle with disease and poverty and the work for the benefit of the children and the helpless the Census statistics are invaluable," he wrote.

Those "helpless" were counted with the help of a Salvation Army free-meal-and-census evening featuring a menu of bread and mutton soup.

And afterwards, the Times was delighted to report that the suffragettes had failed to avoid being counted. It puts the recent international Jedi census stunt - where people listed their religion as Jedi in tribute to Star Wars - into perspective.

Looking at the 2011 census, the irked members of the King family might have been surprised to see questions on type of heating, ethnicity and religion. Or the baffling question 17: "This question is intentionally left blank go to 18."

The observer from 1911 might also wonder at our obsession over the minutiae of working life. Take question 28: "If a job had been available last week, could you have started it within two weeks?"

If the government of 1911 was curious, the government of 2011 is ravenous for knowledge.