Famous opening lines from Twitter, mobile phone and e-mail

- Published

- comments

Twitter launched five years ago with the simple message "just setting up my twttr". In the same way, many technological breakthroughs that ultimately shaped the world began life, not with a fanfare of trumpets, but with a few humble words.

"Alright, so here we are in front of the elephants."

And so with great understatement, the first words were uttered on YouTube, in its first video posted in April 2005.

Me at the Zoo, external depicts co-founder Jawed Karim at San Diego Zoo. And yes, he's in front of the elephants.

Six years, and billions of page views later, YouTube has become part of the media landscape, used by the Queen, world leaders and the owners of pets that do weird things.

If Karim knew back then how big his new venture would become, maybe he would have given that first video more of a sense of occasion. But maybe not. Every new phenomenon has to start somewhere, after all.

And now Twitter's first forays into the 140-character world are being remembered as it marks its fifth birthday. On 21 March 2006, an automated message from founder Jack Dorsey said "just setting up my twttr", external, then the first human tweet was sent when he typed the two words "inviting co-workers", external and hit send.

Considering those two tweets led to billions more, it was an underwhelming start, rather like taking the first steps into an exciting new world, but instead of making a grand entrance, slipping in the back door and wiping your feet on the mat.

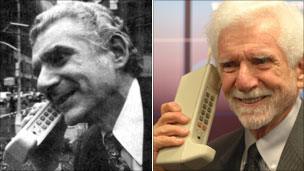

Older technologies started in similar fashion. Martin Cooper is the man credited with making the world's first call from a truly portable mobile phone, from a New York pavement on 3 April 1973.

Speaking from the US this week, the 82-year-old recalled the moment when, as a 45-year-old research director leading a team at Motorola, he made the historic call using a prototype Dyna-Tac. Although reporters were present, it wasn't recorded.

"I was calling Joel Engel who was my antagonist, my counterpart at AT&T, which at the time was the biggest company in the world. We were a little company in Chicago. They considered us to be a flea on an elephant.

"I said 'Joel, this is Marty. I'm calling you from a cellphone, a real, handheld, portable cellphone.' There was a silence at the other end. I suspect he was grinding his teeth."

The conversation was very brief, says Cooper, now chief executive at ArrayComm. So how much did he agonise over his words? Not a lot, it seems.

"It was spontaneous. I was talking to a reporter trying to think up something clever to say, like I am now, then I did it. It was just that.

A big call on a big phone - Cooper in 1973 and now

"You never know when you do something like that, that it was the momentous occasion which it turned out to be. The issue at the time wasn't about creating a revolution, although that was what happened. It was about stopping At&T."

Above all, he says, he was hoping the call worked. And following that brief exchange of words, a worldwide telecoms industry has since sprung up, along with a vast array of mobile phone technologies that continue to shape how we live.

A hundred years before Cooper made history, Alexander Bell tested his new invention - although many dispute whether he was the first - of the telephone, by ringing his assistant in the next room. "Mr Watson, come here. I want to see you," were his first words.

By the time the UK's first trunk telephone call, without the help of an operator, was made in 1958, there was more of an expectation that here was a moment to savour. The Queen began the call by saying: "This is the Queen speaking from Bristol. Good afternoon, Lord Provost."

And 11 years later, Neil Armstrong uttered some of the most famous, and hotly debated, words ever spoken when he took the first human steps on the Moon's surface: "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."

Those words set the benchmark, says speechwriter Max Atkinson, because they have so endured so well. One of the rules of a great line is to invoke a contrast, which Armstrong does beautifully.

But there was probably some input from Nasa about what the first man on the moon was going to say, says Atkinson. Launching an embryonic dotcom is different and it's only with hindsight that we realise the super-successful internet ideas started off with two audiences - those there are at the time and history.

It would be a mistake, he says, to think too much about history. That's why the words expressed at the launch of so many technologies, mundane though they are, should be admired for their refreshing modesty.

The first e-mail is a case in point. Computer engineer Ray Tomlinson is believed to have sent it in 1971, from one computer to another in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The test messages were forgettable, he said. "Most likely the first message was QWERTYUIOP or something similar."

It shows how much the world has changed that expectations when these kinds of projects start out are not set too high, says Paul Armstrong, head of social media at Mindshare, a media agency based in London.

"The world now moves a lot quicker than when the events of 1969 were happening and so although they are monumental as we look back at them, at the time they don't know if they're going to be a success or failure.

"When you're setting something up like that, you don't know yourself where it's going to go, and the success depends on lots of things. For all the ones you hear about it, there are thousands more that don't have the venture capitalist backing."

The founders, some of them household names now, aren't thinking about success and writing something elegant and meaningful, he says.

"They're very much focused on getting something up and running. That's why you're not seeing profound stuff."

So if the destination is all that matters, and not the first tentative steps, perhaps an elephant enclosure is not a bad place to start.