Could a marathon ever be run in under two hours?

- Published

- comments

As thousands prepare for the London Marathon, the very best among them face perhaps the most awe-inspiring barrier in sporting endeavour - the sub two-hour marathon. But can anyone break it, asks Chris Dennis.

A marathon of 26.2 miles (42.2km) in 120 minutes - the very thought takes my breath away.

Expert opinion on whether it is possible is intriguingly divided.

For some it is the next great sporting barrier to be broken, for others it will always remain beyond the limit of endurance. Could it happen at the 2012 Olympics?

The current world record holder, Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie, external, who ran the 2008 Berlin Marathon in 2:03:59, has no doubt it could be done, but not in the next few years, ruling out the next Games.

The 38-year-old tells me: "No question. The first sub two-hour marathon will need 20 to 25 years, but it will definitely happen."

Britain's top woman runner and world women's record holder Paula Radcliffe agrees.

"Records are there to be broken and people are going to be shooting for it, but someone is going to have to run really hard to beat this one. That's the kind of mindset it will take."

Even the thought that it could be broken within a generation causes excitement.

"I'm 60. If I've got my figures right, I'll live at least 20 years, so I believe in the next 20 years we will see the first sub two-hour marathon," London Marathon race director Dave Bedford says.

But the reigning Olympic men's champion, 24-year-old Kenyan Sammy Wanjiru, who ran the distance in 2:06:32 in Beijing, believes it is beyond his own abilities.

"For me it's impossible to run two hours, but two hours two minutes, it's possible. Maybe the new generation... you could get strong people. But in this generation, you cannot talk about two hours."

Another sceptic is Glenn Latimer, one of the leading authorities on marathon running in the US. He doesn't believe it can happen in his lifetime. "Maybe that's because I'm old, but I don't see it happening in a long, long time.

"You watch these great athletes up close, an athlete as great as Haile Gebrselassie... and you could see the strain, he looks magnificent through 20, 21, 22 miles and then it starts, and then the body starts to break itself down and maintaining pace is hard enough," he said.

They both believe the record will come down to two hours and two minutes, at which point it will plateau.

Then again, 60 years ago people were saying the same thing about the four-minute mile, before Roger Bannister came along.

The science of endurance running is highly complex, but physiologically, there are three main factors which determine how quickly someone can run:

their maximal rate of oxygen consumption, known as VO2 max

their running efficiency - how quickly they can cover the ground

their endurance capability - what percentage of their VO2 max they can sustain

Opinion among sports scientists varies on exactly where the limit of human endeavour lies. For some, Haile Gebrselassie's current record is already pretty close, for others, there is still a way to go.

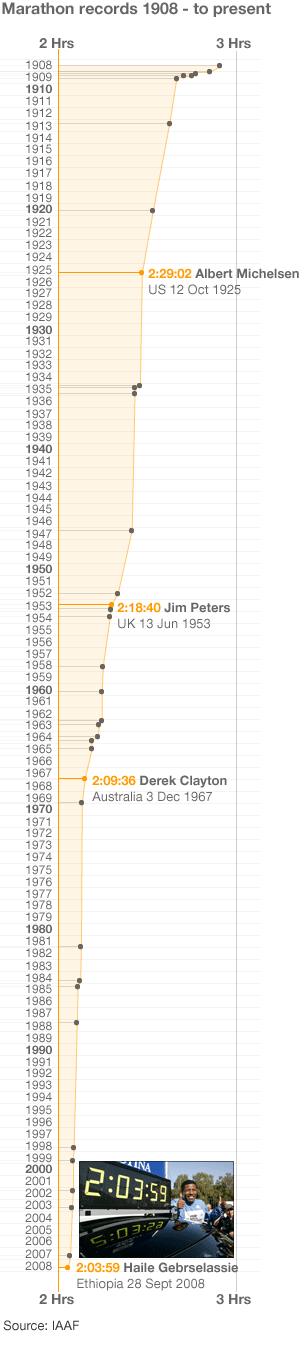

Looking at the progression of the marathon world record is fascinating.

Reducing it from 2:16 to 2:12 took seven years, 2:12 to 2:08 took 19 years, and cutting it from 2:08 to the current mark of 2:03:59 took 24 years.

By analysing actual performances and extrapolating, Francois Peronnet, a professor at the University of Montreal, calculates that the first sub two-hour marathon will be run in the year 2028.

Whenever it happens, it would mean running each mile at a four minute 35 second pace. By comparison, a decent club runner might run at a seven-minute mile pace, and a casual runner at nine or 10 minutes.

I have experienced first-hand what it would feel like to run at sub two-hour marathon pace. For just a fraction of the marathon distance.

Hooked up to a state of the art treadmill at the English Institute for Sport at Loughborough University, Leicestershire, under the guidance of two of the country's top physiologists, I ran at a 4:35 pace for 10 seconds.

It was tough - and the thought of doing it over 26.2 miles for up to 120 minutes was simply mind-boggling.

'Perfect mix'

Where most experts agree is that the first sub two-hour marathon will need several factors to come together on one day in the perfect mix.

"If on the day of competition you miss one thing, you miss everything," Gebrselassie says.

First, it will need an elite athlete in tip-top condition, probably one from east Africa.

Second, it will need to be on a fast, flat course such as Berlin, London or Rotterdam. Berlin is known as one of the quickest and has produced four world records in the last 10 years.

Third, perfect weather conditions. No wind and temperatures of around 10-15C.

Fourth, decent pace-makers to lead the race and take the elite round at the right speed.

Finally, money.

As the marathon gets closer to the magic mark, race directors will dangle huge financial carrots to incentivise runners to break it. The first person to dip under two hours will run into the record books a very rich person.

Radcliffe knows what it feels like to experience a perfect mix. Back in London in 2003 she blew the women's world record (which she had set the year previously) out of the water by setting a new mark of 2:15:25.

"The fact that you feel like everything was flowing. It wasn't forced. Nothing hurt. You're not even thinking - you're just running. It's just second nature, you've trained so hard for it and race day feels easier than the training that you've done," she explains, describing the feeling of being "in the zone".

By common consent in running circles, the first two-hour marathon will be run by someone from Ethiopia, Eritrea or Kenya. But why?

I spent a few days in Ethiopia with some of the country's top runners and coaches.

Ethiopia may be one of the poorest countries in the world, but it has a formidable track record.

The likes of Abebe Bikila, Mamo Wolde, Miruts Yifter, Kenenisa Bekele, and the man they call the Little Emperor, Haile Gebrselassie, have all rolled off the country's running conveyor belt over the years.

Most of them started running soon after they could walk. Those born in the countryside, such as Gebrselassie, would run 10km (6.2 miles) or more to school and back every day. There was no other way of getting there.

Add to that the altitude (capital Addis Ababa is 2500m (8202ft) above sea level), a simple diet of mainly organic food, good weather and an extraordinary work ethic, and you see why the country's runners are so successful.

Training with Ethiopia's elite youth runners proved they had the determination and dedication needed

For Ethiopia's elite athletes life is almost monastic - run, eat, sleep. Then run, eat, sleep. There is very little time for anything else.

I was lucky enough to join one group for a training session at sunrise on the outskirts of Addis. Just one 5km (3.1 mile) loop at moderate pace left me gulping for air, but for the elite runners, that was merely a warm-up.

I also met youngsters from Ethiopia's next generation of marathon runners - could one of them be the next Haile Gebrselassie and possibly the world's first sub two-hour marathon runner?

Their dedication and self-discipline are both humbling and awe-inspiring. Many of them feel it is their national duty to maintain Ethiopia's position as the top distance-running country in the world.

If in 20 years the marathon record is reset at 1:59:59, do not be surprised if it is done by an Ethiopian.