Can forgiveness ever be easy?

- Published

- comments

Much discussion about forgiveness is in terms of religion

We occasionally hear inspirational stories of victims and relatives who forgive abusers, murderers and even war criminals. But just how easy is it to forgive?

The brother of murdered 16-year-old schoolgirl Agnes Sina-Inakoju said recently he would be prepared to forgive her killers.

"If they can forgive themselves for what they have done I would forgive them," said Agnes's older brother, Abiola Inakoju, after the conviction of two men for her murder.

Agnes was fatally wounded at a takeaway shop in Hackney, London in April 2010, the innocent victim of gang violence.

But forgiveness is a complicated and emotive issue. Despite saying he could forgive them, Inakoju also said he would not be able to talk to the killers.

Agnes Sina-Inakoju's brother says he can forgive her killers

"Talking is about having a civilised conversation - you exchange words which are meaningful," he said.

"We would not be able to talk, we would shout."

So what does true forgiveness really mean? And how can it be achieved?

Throughout history, forgiveness has often been seen through the prism of religion, rather than of science or psychology.

On Good Friday, the Bible says Jesus Christ said "forgive them Father for they know not what they do" as he was on the cross.

"Freud only mentioned forgiveness three times in his collected works," says psychologist Prof Ann Macaskill, of Sheffield Hallam University.

"Each time, this is in a religious context. Forgiveness was a religious topic, not a scientific one, and this only changed very recently.

"Especially if people are religious, they feel as though they have a moral obligation to forgive. In a study of how forgiving clergy were, we found they were unbelievably forgiving, but they had to work very hard at it."

The most obvious example of this is the Catholic confession, where sins can be absolved. But forgiveness between individuals can be complicated.

And Prof Macaskill believes that forgiveness is something that is often misunderstood.

"We're very sloppy in the way we use the language of forgiveness," she says. "Take, for example, if a husband has betrayed his wife in some way. She may say 'I forgive you' but what she's actually saying is 'I will try to forgive you' and this takes time.

"What actually happens is that what has been 'forgiven' is still brought up all the time and argued about."

That domestic example many people can identify with, but can we understand the conflicting emotions in forgiveness of abuse, murder or genocide.

Anti-apartheid activist Father Michael Lapsley lost both of his hands and one eye when a bomb was concealed in a packet of magazines in South Africa.

"Sometimes, we as church people have communicated that this is something glib, cheap and easy," he says. "In my experience, I have found that most human beings have found it costly, painful and difficult and yet, it can be a key to extraordinary things.

"In South Africa, I know of no example of anyone where anyone sought revenge [after the restorative justice programme which followed apartheid] - it was enough for them to know and see what happened to them acknowledged."

Fr Lapsley is not bitter about what happened to him, but the person responsible has never come forward and he is not sure what it is to forgive an abstraction like the act itself.

"There is a principle, it's not to do with religion, that only the victim can forgive the perpetrator," says Chief Rabbi Lord Sachs.

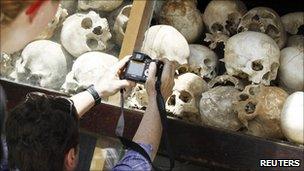

"The victims of the Holocaust are no longer alive, so forgiveness [for these acts] belongs to heaven, not to earth, and we've kind of worked on that basis.

"Holocaust survivors' main concern was turning their eyes to the future and simply surviving and they understand that hate, and memories as a whole, is a terrible weight you have to let go."

It is hard for many people to understand how killings or torture could be forgiven

This difference is one that psychologists have come to define.

"There is a distinction between making the decision to forgive - which we call decisional forgiveness - and actually forgiving someone - emotional forgiveness - which takes longer," says Professor Macaskill.

Often people say they've forgiven but will never forget. Some might argue that's not really forgiveness, but rather the act of drawing a line under an event.

"That's confirmation that they still don't really trust the person. They are always recalling how they were treated before."

And Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams is keen to warn of the danger of confusing the two and encouraging "easy" forgiveness.

"The 20th Century has seen such a level of atrocity that it's focused our minds very hard on the dangers of forgiving too easily because it would be as though the suffering wouldn't matter," he says.

Many people understand forgiveness to come from the victim, but what happens if the victims are dead?

"To say 'oh well, just forgive, that's what you're meant to do', we realise - as perhaps we might not have done a century ago - what we're asking there - there is something quite horrifying about it.

"We've also learned, I think, it won't just do just to say to other people 'you must forgive'. We've learned it's a process that can take a long time. It can be a matter of going deeper into the hurt rather than out of it.

"Even when you have the most justified hurt or resentment... you have to let go of that for your own good. What those words [of Jesus on the cross] tell us is both that it's possible and that it isn't easy."