Did Tupperware parties change the lives of women?

- Published

- comments

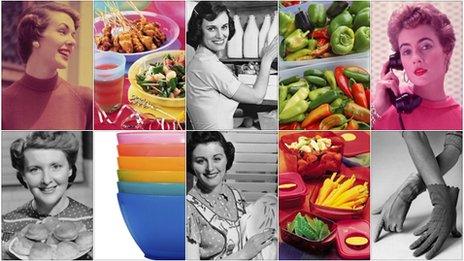

Tupperware is planning on relaunching in the UK five decades after its first British sales party. But did the brand propel suburban women into the world of entrepreneurship or reinforce stereotypes?

It conjures up an era when throwing a party to sell airtight storage containers was the pinnacle of a lady's social calendar.

Think Tupperware, and the associations are of a retro, pre-feminist world in which housewives briefly put aside their aprons to discuss the best way to store their husband's dinner ingredients.

To its critics, the brand symbolises an era in which female lives revolved around domestic drudgery.

But to its latter-day enthusiasts, it represents a breakthrough by millions of ordinary women into the world of business which left a small but highly significant dent in the glass ceiling.

It was an effort that laid the foundations of a global empire. Today, Tupperware Brands Corporation boasts worldwide sales revenues of $2.1bn (£1.3bn) from across almost 100 countries.

Now the company is preparing for a marketing push in the the UK market after an eight-year absence. And what experts agree was crucial to achieving worldwide ubiquity for this practical product was the hitherto commercially untapped power of female friendship.

The famous Tupperware parties, at which the containers were sold, were prototype girls' nights in, as much about getting to know one's neighbours as they were about commerce.

Briefly liberated from their domestic routine, guests would play games such as "Waist Measurement" or "Write An Honest Advert To Sell Your Husband" before being sold Wonder Bowls and Ketchup Funnels.

From a 21st Century perspective, it may sound demeaning.

But according to Alison Clarke, professor of design history and theory at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna, and author of Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America, the parties were revolutionary in that they offered an alternative model for commercial success based around female co-operation rather than aggressive competition.

"The actual networks of Tupperware parties were about women helping other women and enabling them," Prof Clarke says. "It wasn't discussed as work - it was an extension of socialising.

"It was the antithesis of male corporate culture. It was the opposite of Mad Men."

Indeed, Tupperware - launched onto the market by inventor Earl Tupper in 1946 - had languished in the market until the intervention of the extraordinary proto-businesswoman who pioneered the company's "party plan".

Brownie Wise, abandoned by her husband, struggling to meet her sick son's medical bills, had begun selling the containers to make ends meet. By 1948 she was selling $1,500 (£915) of products every week and Tupper appointed her as his head of home sales.

The model quickly grew into a world-wide, multimillion-dollar success. Just as Tupperware was marketed as a space-age labour-saving component of the new consumer era, so too was Wise herself an early embodiment of post-war feminist demands that women should be given the opportunity to succeed in business.

In 1954 she was the first woman to appear on the front cover of Business Week magazine, pictured sitting in a peacock chair surrounded by young male executives. With her pink Cadillac and a canary dyed to match, her lace dresses and pet palomino pony, her public image married aspirational ambition with femininity.

Indeed, Prof Clarke argues that Wise symbolised the real beneficiaries of Tupperware, women who would not have found it easy to enter the world of business - very often those from ethnic minorities or divorcees, like Wise herself, who needed the work.

Tupperware is preparing to re-enter the UK market

And it was a business model that proved successful around the world, the first British Tupperware party in Weybridge, Surrey in 1960 introducing UK suburbia to the Square Seal Freezer Box, the TV Tumbler and the Spindly-Legged Salt and Pepper Set.

But Wise also personified the precarious position of female executives in the era. In 1958 she was dismissed from her post, despite being the single biggest driving force in the company's success, apparently because the puritanical Tupper disapproved of her flamboyant lifestyle.

Indeed, critics of the Tupperware sales format argue that this brutal ejection reflects the way in which the business model ultimately exploited women.

Susan Vincent, professor of anthropology at Canada's St Francis Xavier University, says that rather than breaking down barriers, Tupperware perpetuated gender stereotypes.

"It always assumed a close association between women and the domestic sphere," she says.

"Plus, the exploitation of social networks is ultimately quite destructive. It relies on family and friends - not for social support, but it commercialises them."

It was, however, a formula that proved commercially successful. By the 1990s, 90% of US homes owned at least one item of Tupperware.

Yet in the UK, as the notion of women earning their own money became more familiar, sales began to drop off.

Other companies which adopted the party format, such as Ann Summers and the Body Shop, were able to entice guests with a focus on indulgence rather than housewifely duty.

In 2003, Tupperware parties were axed in Britain with the loss of 1,700 jobs.

Now, however, the company is preparing to re-enter the UK market. Richard Brett of London public relations agency Shine, which has been hired by Tupperware to spearhead its re-launch, believes a crucial component of the Tupperware brand is the role it played in bringing about social change.

"Part of Tupperware's whole story is the way they have empowered women historically, and still do so today all over the world," he says.

Not everyone would agree that its legacy was so positive. For others, however, Tupperware will always come with a seal of approval.