Why is the word 'slut' so powerful?

- Published

- comments

Women in North America have been marching over the use of the word "slut". But why does the word have the power to arouse so much passion?

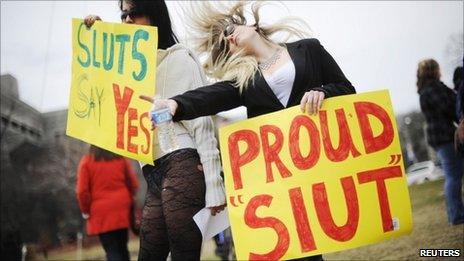

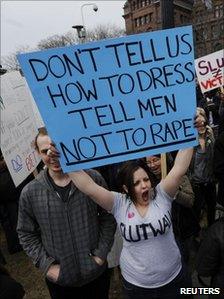

Thousands of women in the US and Canada have marched in response to a Toronto police officer's comment that women should try not to dress like "sluts" to avoid being raped or victimised.

As well as opposing the notion that female victims may have helped provoke attacks, many of the women - who call their protests SlutWalks - are attempting to reclaim the word itself.

"Slut" is now commonly used on both sides of the Atlantic to refer to promiscuous women in a derogatory fashion.

Despite feminism and the sexual revolution, the word slut still reverberates with negative connotations linked to sexual promiscuity, and it is still applied predominantly to women rather than men.

Growing trend

"Historically, the term 'slut' has carried a predominantly negative connotation... whether dished out as a serious indictment of one's character or merely as a flippant insult, the intent behind the word is always to wound, so we're taking it back," a statement on the SlutWalk website reads. "'Slut' is being re-appropriated."

Crowds took to the streets in Canada to protest against rape

So far, SlutWalks have taken place in Canada and the US, but events are being planned in the UK and Australia.

This is part of a growing trend to "reclaim" words that have been given a negative connotation, says TV lexicographer Susie Dent.

"Gay culture reclaimed the word 'queer'," she says. "It is about picking these words up and using them with pride."

Psychoanalyst and social critic Susie Orbach says she loves the idea of woman trying to reclaim the world slut "in order to take the sting out of it".

"The problem with the word slut is that it has cut women off because they have an energy around their sexual desires and we are still so prejudiced about this. But if we reclaim the word, it simply becomes an issue of 'so what?'."

Many women argue that the very word slut is an embodiment of the double standards employed when discussing the sexual appetites of women and men. Women are described as sluts, while men are often referred in a less derogatory light as "studs" or a "ladies man".

The word has managed to retain its currency, says Susie Dent.

"Words like tarty or strumpet appear very old-fashioned but slut seems to still have a powerful connotation," she says.

"This could partly be because it is short and pithy and you can say it with power. Also, it has never deviated from its original roots.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word "slut" has a number of meanings. From the Middle Ages onwards, it was used to describe "a woman of dirty, slovenly, or untidy habits or appearance". This is a meaning that many older people would use it for even now.

"The earliest citation of the word was 1402," says Lisa Sutherland, commissioning editor at Collins Language. It was used by Thomas Hoccleve in the Letter of Cupid to describe someone who was slovenly or dirty.

"It was definitely a pejorative reference," says Sutherland, "but it wasn't always used in that way". Samuel Pepys referred to his servant girl as being an "admirable slut" in a playful, affectionate way in 1664, says Sutherland. "John Bunyan also used it playfully in 1678."

Its alternative meaning describing a "woman of a low or loose character" or a "bold or impudent girl or a hussy" was first cited in the late 15th Century, but it wasn't until the 19th Century that this usage really began to develop. Charles Dickens, for example, used it in Nicholas Nickleby.

"There was a big spike in its use in the early 1920s," says Sutherland. "This was just after the end of World War I. Women had gained independence, this might have frightened men because women were encroaching on areas they used to dominate. Women were going out, they were drinking and they were being referred to in a derogatory way."

According to Collins, there was also a spike in the 1980s.

"According to our records, common references were 'little slut' and 'cheap slut'," says Sutherland.

The alternative meaning had a slight resurgence in the 1960s, when journalist and broadcaster Katharine Whitehorn identified herself with the "slovenly women" in an article entitled Sluts.

Katharine Whitehorn before she identified herself with the 'slovenly women'

"Have you ever taken anything out of the dirty-clothes basket because it had become, relatively, the cleaner thing? Changed stockings in a taxi? Could you try on clothes in any shop, any time, without worrying about your underclothes? How many things are in the wrong room - cups in the study, boots in the kitchen?" she wrote.

The right answers, said Whitehorn, make "you one of us: the miserable, optimistic, misunderstood race of sluts."

But today in the UK, it is probably only your grandmother who will continue to use this reference.

Language has the capacity to change, but will the efforts of the women behind the SlutWalk be successful?

"It has a good chance of being reclaimed by the 'right' people," says Dent. "But it will remain offensive if it is used by someone not in that group, by those outside the 'in crowd'."