Memory and method: In praise of learning by rote

- Published

- comments

Pupils across much of the UK are in the last week of revision for GCSEs, but is learning off by heart still a practised and valued skill, asks Neil Hallows.

The Dickens character Thomas Gradgrind ensured his pupils had "imperial gallons of facts poured into them until they were full to the brim". There are those who despise his methods, but would still like to borrow his measuring jug.

GCSEs and A-levels tend to include non-exam elements like coursework, supervised assessments, and extended essays, as well as exams spread over a period of study. Some say this makes the experience more lightweight, others that it tests pupils' level of understanding in a more rounded way.

Common ground can be hard to find, but here is a striking point of consensus. There are millions on either side of the educational debate who cannot even remember their online banking details.

Students could be forgiven for asking why they have to cram such subjects as glaciation and inert gases when as soon as they put their pens down in the exam hall for the last time, they no longer have to remember anything - even short, useful pieces of information.

We know even less than we think we do. We start Auld Lang Syne and My Way with a confident roar, then find the second verse as elusive as our audience.

But does it matter? It's the information age, remember, and if it's all on a phone or a computer, does it need to be in our heads?

There are plenty who need not just a pretty good processor in their heads but plenty of Ram too. They are in professions like medicine or law, the study for which is compared to learning a whole new language, and many others we might take for granted.

London black-cab drivers need a detailed knowledge of a six-mile radius of Charing Cross station. They learn 320 routes, and all the landmarks and places of interest along the way. The process can take three to five years, and dropout rates are said to be around 80%.

There's controversy over how much rote learning teenagers should have to do

Nick O'Connor, from Essex, is making good progress after 22 months of study. He says: "It doesn't need a specific person or a specific brain. It's just about being structured and having the motivation to get up every single day and go out on the bike [to research the routes]. I'd say anyone could do it."

He typically spends two hours before work driving the prescribed routes, and also pores over maps and past exam questions. Given that his day job is at a London knowledge school, WizAnn, the city's streets are rarely out of his mind.

But dare one mention the word "sat-nav"? O'Connor is confident that man can beat machine. "It's about speed of thought. Before you can even punch an address into a sat-nav, the cab driver is often on his way because he knows exactly where he needs to go."

A taxi driver may annoy a customer when the memory fails, but for performers it is much worse.

Actor and writer Michael Simkins calls it the "ultimate nightmare". He recalls the one occasion when it happened on stage. Tired, through working on other projects, he forgot his lines in a big speech.

"It really shook me. It must have taken me 10 or 12 weeks to fully recover. After that I was going through my lines in the wings every night, which can be a fatal thing because it can breed further terror. I can still sense the scar tissue 25 years later."

Simkins, who has appeared in a large number of stage and TV roles, says actors learn lines in very different ways. Some, like him, learn "by Victorian rote" in advance, while others pick them up later, at the rehearsal stage. And the demands of recurring dramas and soaps have produced a skill all of their own.

"When you work in soap operas, you find the regulars turn up barely knowing their lines. They have an ability to learn lines at colossal speed, and then if you ask them the next day what their lines were, they're not able to tell you. It's a remarkable thing."

He says actors are good at covering mistakes, and audience members are unlikely to know the exact script, so most go unnoticed. When they are spotted, context is everything. A mistake followed by a swift, witty recovery in a comedy can "really get the audience on your side". In a tragedy, less so.

Graver than tragedy, and indeed life itself, was the situation in which Christina Aguilera found herself earlier this year when she mangled part of The Star-Spangled Banner at the US Super Bowl. Televised cock-ups get flagged up so quickly and passionately on Twitter and YouTube that performers can sometimes earn notoriety for a single error.

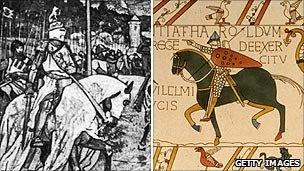

Scottish and English pupils can usually remember the dates for Bannockburn/Hastings

For the rest of us, learning precise chunks of information may not be necessary for our financial survival, but it can bring an unaccountable pleasure.

Some, mainly older, readers could launch effortlessly into several verses of Tennyson or Kipling they learned at school. Remembered poems are often described as a "consolation", be that on a dull bus journey or during times of adversity.

Today's primary school children tend to learn songs and lines for a play, as well as useful tools like times tables, says Mark Brown, head teacher of St Mary's Catholic Primary School in Axminster, Devon, but rarely whole poems, as their grandparents would have done.

The ability of children to soak up and precisely recall information is often underrated. Brown recalls a nativity play in which the boy playing Herod was off sick. "One of the children came in and said 'I'll play him. I know all the words.' In fact most of the children in the play knew all the words. To know one part, you need to know everyone else's part."

Poetry recital was highlighted in the BBC's Off by Heart competition, where in 2009, thousands of primary school children learned and performed poems and, this year, secondary school pupils will begin tackling passages from Shakespeare.

The first 12 Off by Heart finalists had neither the unsettling precociousness of spelling bee champions, nor much whiff of an elocution lesson. The winner, 10-year-old Yazdan Qafouri, was from an Iranian family granted asylum in the UK, and had once lived in a tent. He seemed to exorcise the ghost of Miss Jean Brodie from recitals.

But there is an undoubted element of power and status in knowing not just information, but a distinct quotation or verse. In Yes Minister, Sir Humphrey and his civil service colleague Bernard Woolley regularly flaunt their classical education with word-perfect Latin and Greek quotations they know their boss will not understand.

And could you imagine Gandalf plodding his way through a spell book instead of issuing a majestic incantation? Or the late Keith Floyd using a recipe book?

Or not being moved by a five-year-old, his face wrinkled with effort as he recites how full they are at the inn? It's not called "off by heart" for nothing. Magic doesn't come off a cue card.