Operation Crossbow: How 3D glasses helped defeat Hitler

- Published

- comments

Newly released photographs show how a team of World War II experts disrupted Nazi plans to bombard Britain - with the help of 3D glasses like those in modern cinemas.

Hitler's deadly V-1 and V-2 missiles were early but effective weapons of mass destruction - unmanned flying bombs which brought terror to southern England.

But their impact could have been all the more devastating - costing thousands more lives, lengthening the war and threatening the D-Day landings - were it not for the fact that British intelligence worked in three, rather than two, dimensions.

One of the Royal Air Force's most significant successes came with Operation Crossbow, when it tracked down, identified and destroyed many of the V-weapons which could have prolonged the war.

It did so by meticulously photographing the landscape of occupied Europe in a way that allowed officers to study every contour.

Now the pictures have been brought to life using computer graphics in a BBC documentary thanks to research by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

During the war, the images were painstakingly analysed by a team of photographic interpreters - known as PIs - at RAF Medmenham in Buckinghamshire.

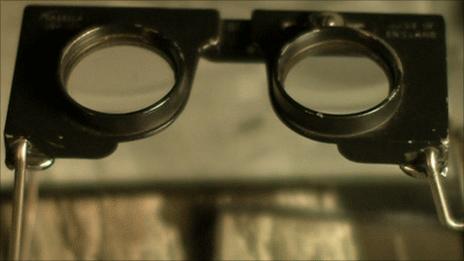

Their secret weapon was a stereoscope - a simple Victorian invention which brought the enemy landscape into 3D.

Working on the same principles as modern-day 3D glasses, it allowed the PIs to measure height, especially of unidentified new structures - such as rockets and their launch sites.

This technique was to prove decisive, and it saved thousands from the V-missile barrage.

The Spitfire is well-known for the role it played in the Battle of Britain, but less celebrated is its contribution to this crucial phase of the conflict.

How Hitler was defeated with the aid of 3D imagery, as explained by Operation Crossbow

Pilots from the Photographic Reconnaissance unit, created in 1940, risked their lives by flying unarmed over Europe to take tens of millions of photographs, generating 36 million prints.

To make the 3D effect work, images had to be captured in carefully-plotted sequences which would overlap each other by 60% so everything would stand up when viewed through the stereoscope.

It made the job of the pilots - who, in addition, had to avoid enemy fire - an especially skilled and arduous one. Flying at 30,000ft, they were unarmed because of the weight of the five cameras carried on each Spitfire.

But it is a role of which 88-year-old Jimmy Taylor, a former reconnaissance pilot and the only survivor from the squadron, remains immensely proud.

"It was the best job in the RAF," he says. "We flew the most beautiful aeroplane, the fastest of its day.

Jimmy Taylor remains proud of the part he played in disrupting Hitler's missile programme

"We had no guns, no bullets, so I didn't kill anyone. Physically, there's nothing left of the air fights, nothing left of the bombing - but the photographs are still with us, and they're still useful."

Arguably, the squadron's crowning moment came with Operation Crossbow.

It began in 1942, when a Spitfire flying over Peenemunde in north-eastern Germany spotted an airfield with three concrete-and-earth circles.

Initially, PIs studying the photos thought nothing of them.

In fact, Peenemunde was a vast research centre developing the V-missiles which the Nazis believed would win them the war.

This plan was disrupted, however, in 1943, when British intelligence had managed to bug a conversation between two captured German generals about the weapon.

British spy planes scoured Europe and PIs were ordered to find clues.

Using 3D, a PI managed to spot an upright tube in one of the circles at Peenemunde. From its shadow, the PIs deduced that it was a rocket some 14m high.

Geoffrey Stone, now 92, worked as a PI at Medmenham and says being able to view the images in three dimensions was crucial.

The Germans worked tirelessly to create the V series missiles, the most sophisticated weapons of their time

"You needed to be good at paying attention and have the ability to concentrate - there was so much you had to infer from small details," he recalls.

"We would work late into the evening, but we didn't complain. There was no other way of telling what was going on in central Europe."

Furthermore, alarming photos revealed a network of bunkers in France. The "heavy sites", as they became known to the British, were within range of London.

Reconnaissance flights were sent to investigate, with some daredevils flying as a low as 30m to get the clearest possible images. Back in Medmenham, the PIs correctly identified these as launch platforms.

On 17 and 18 August 1943, 500 bombers set off to destroy Peenemunde and the heavy sites. Crews were left in little doubt of the importance of the mission and told they would have to go back if the sites were not eliminated.

These raids disrupted the V-2 programme and killed senior Nazi scientists.

Production of the V-weapons was relocated to Poland and Germany - out of range of Spitfires. A mountainside in Thuringia, central Germany, was turned into a factory with 60,000 slave labourers.

With this site impenetrable to bombers, the only solution for the British lay in finding and wiping out launch sites in northern France. The French Resistance passed on details of possible sites for the RAF to photograph.

PIs scoured the images for evidence of concealed ramps. Sure enough, woods full of new buildings were soon detected. In total, RAF Medmenham identified 96 "ski sites" - so called because each had a long building that looked like a ski.

In late 1943, the photos made it clear that the Nazis were on the verge of launching a bombardment of southern England. With the planning of D-Day well under way, the timing could not have been worse.

Operation Crossbow was launched late 1943 and bombing of the ski sites began two days before Christmas.

The bombardment was effective but it was not enough to halt the missile programme altogether.

A photographic interpreter spotted the missile in the top-centre-left of this picture

The V-1 - known as the doodlebug - landed in London in the summer of 1944, bringing terror to the capital. The Germans were using less conspicuous launch sites, and brought missiles out at the last moment.

But these sites were identified by PIs who spotted scarring on the land caused by the jets' booster motors dropping off. These sites were targeted and the doodlebug barrage was limited.

The last V-1 landed on 7 September 1944. The next day, however, the first V-2 crashed in Chiswick, west London. Because it was silent, offering no warning, there was no defence against it.

Since the V-2 was mobile, bombers directed by RAF Medmenham attacked the supporting infrastructure such as roads and railways. In the end, the advancing allied armies over-ran the launch sites.

By the time they were finally halted, the V-weapons had claimed some 9,000 lives - but it could have been many more.

The Germans planned to launch up to 2,000 V-1s every day and, had they been successful, the path of the war could have been altered.

Much of the aerial photography featured in Operation Crossbow was discovered through the research of Allan Williams, curator of The National Collection of Aerial Photography, part of RCAHMS.

While the collection contains millions of images, only a small percentage have so far been digitised and catalogued - but Williams says they tell the story of one of the war's most decisive episodes.

"The British always used 3D and the Germans didn't," he says. "What this meant was that the British could make enemy territory come to life.

"Without this photographic intelligence - which was created at remarkable speed - the Germans could have launched potentially devastating attacks on Britain before D-Day that could have easily changed the outcome of the war."