Who, What, Why: What is planking?

- Published

A man has died in Australia after taking part in the internet phenomenon of planking. But what is it and where did the craze come from?

The victim, a man in his 20s, fell from a balcony railing in Brisbane while a friend photographed him, according to police.

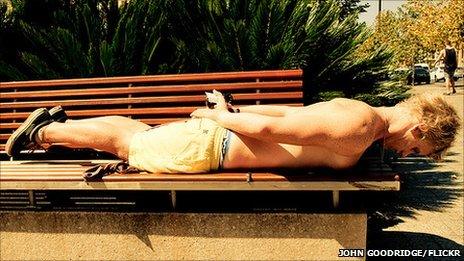

The phenomenon of planking involves lying face down in a public place - the stranger the better - and posting photos on social networking sites such as Facebook. Aficionados lie expressionless with a straight body, hands by their sides and toes pointing into the ground.

Two groups claim to have invented the prank - either in Somerset in 2000 as the "lying down game" or eight years later in South Australia as planking. Both groups have rival Facebook sites boasting more than 100,000 fans.

Planking has grown in popularity, particularly in Australia where there has been huge media coverage. An Australian rugby league player David "Wolfman" Williams celebrates scoring by planking, while one of the nation's leading chatshow hosts Kerri-Anne Kennerley opened a show last week by planking on the TV sofa.

In the same week police served a trespass notice on a man caught planking on a squad car.

Now, following the first planking death, Queensland police have warned pranksters that they may be charged with "unauthorised high-risk activity" and Prime Minister Julia Gillard has advised people to be careful.

Lying down

Despite its Australian popularity, the earliest practitioners were Gary Clarkson and Christian Langdon in 2000, who started lying down in public places in Taunton in order to be photographed. They called it the lying down game.

Then in 2007, their friend Daniel Hoppin took the phenomenon online. "They'd started lying down in bars and clubs to try to spin people out. So we began a Facebook group to see who could get the craziest photo."

Flashmobbing, like planking, is an example of a meme

The British media latched onto the craze in July 2009, with the result that the Lying Down Game Facebook page went from 8,000 to 35,000 members. It now has 107,000 fans.

In September 2009, A&E staff at the Great Western Hospital in Swindon were suspended for playing the game while on duty.

But why lying down?

"Because it's utterly ridiculous," says Hoppin, who now works in the building trade in Sydney. "If you go on holiday, you take a photo of yourself in front of the Eiffel Tower or the Leaning Tower of Pisa. We thought it would be hilarious if you're not interested and lying down instead."

In Australia, the activity was named planking.

"Planking was a term myself and two other mates came up with roughly in the summer of 2008 or 2009," says 25 year-old Sam Weckert, a carpenter living in South Australia.

It started as a prank on dance floors and went on to balancing flat on low-lying objects such as pot plants, post boxes and public bins. Friends then took it to Melbourne, at which point Weckert decided to create a Facebook fan page to share "plank" photos.

"It didn't really blow up until a few local radio stations got hold of it, ran competitions, and it grew very quickly. I never thought it would get to 5,000 or 10,000. But now we have over 120,000 fans."

The growth of planking is an example of the "meme" - an idea that goes viral online and becomes a global trend. Recent examples are Lolcats, Hitler Downfall parodies, flashmobbing and extreme ironing.

"Exhibitionism has been around since the dawn of time," says Nate Lanxon, editor of wired.co.uk. "YouTube and digital cameras just takes it into a whole new realm. The ultimate goal is for your photo to become the most popular."

The essence of planking is not lying "stiff as a board" but juxtaposing it with an unexpected place, says Lanxon. The death in Australia will only accelerate the meme of planking, he says, as people become curious and decide to Google the term.

But for one of the founders of the lying down game, the death has changed everything "Perhaps the magic has gone now," says Hoppin. "I probably won't do it again. People need to concentrate on the humorous ones rather than the extreme, dangerous ones."