How are serial animal killers investigated?

- Published

- comments

Dozens of swans have been slaughtered around the UK this year, a serial cat killer is on the loose in Norfolk, and over the past three decades hundreds of horses have been mutilated. But how is serial animal violence investigated, asks Tom de Castella.

Most people have seen enough television shows and read enough newspaper reports to know what happens when a murder investigation starts.

The crime scene is sealed off, forensic officers move in looking for fingerprints and DNA evidence, detectives go door-to-door. But what's the procedure for investigators when the victim of a killing is an animal?

Every month gruesome cases come to light. Swans are regularly in the firing line. At least 40 of the birds were killed by humans in Somerset during the first three months of the year.

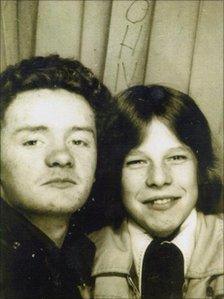

Killers John Duffy and David Mulcahy are believed to have tortured animals

In the last 10 days four men have been arrested over the shooting of eight swans near Stoke-on-Trent. And last week a man was convicted at Harrogate Magistrates' Court of killing a swan with a shotgun.

Meanwhile, the number of cats killed around one street in the Norfolk village of Harleston has risen to at least 10 in the past four years. And since the 1980s there have been hundreds, possibly thousands, of horses slashed, mutilated and sexually assaulted across Britain. In Essex this month a Shetland pony was sexually assaulted and then hacked to death. So how does the RSPCA investigate such violent sprees?

Without witnesses, killings are difficult to crack, says Andy Shipp, a senior prosecution case manager at the charity. "It's pretty rare to just have a dead animal. Unless you've got something else to go on, you're up against it."

Inspectors often employ common police procedures. At the crime scene they take photographs of the dead or injured animal and collect forensic evidence for fingerprinting and DNA testing.

Shipp recalls a case in Staffordshire where a cow was found alive with a crossbow bolt through its head. The local inspector tracked down the killer by collecting DNA evidence from a discarded bolt in the field. The DNA matched up to a young man on the DNA register and he was successfully prosecuted.

A post-mortem examination is carried out by an animal pathologist to establish cause of death, although it may not ascertain precise details, such as which poison has been used.

Collars and microchips can lead investigators to the owner. CCTV footage is another tool that can capture crucial evidence, such as when a woman in Coventry dumped a cat in a wheelie bin.

Inspectors looking for witnesses carry out door-to-door inquiries and if all else fails the RSPCA will make an appeal via the local press.

In extreme cases - such as the killing of swans in Somerset - the RSPCA works closely with police. There have been no convictions for the killings but a man has been charged with the unlawful possession of a shotgun.

The RSPCA can also bring in its own Special Operations Unit, a plain-clothes team with expertise in surveillance and forensics used to tackle dog fighting and badger digging.

According to Barry Fryer, chief superintendent of the unit, forensics is becoming increasingly important. "If a man has got badger blood on his jeans we can compare it with an animal at the crime scene. Our database will show the odds of those two samples being the same and link it to the criminals."

Fingerprinting is one avenue for evidence gathering

Soil on boots can also be traced to a specific area, as can pollen - the latter a technique used in the Soham murder trial to link Ian Huntley to the ditch where his victims were dumped.

But most investigations are hardly hi-tech, says Simon Evans, an RSPCA inspector in the Rhondda Valley. Unlike the TV show CSI, there are no white protective suits - RSPCA inspectors wear nothing more exotic than gloves. Neither do they carry out psychological profiling of suspects.

"You rely on that person making a mistake and being seen or leaving DNA at the scene," he says. "When people come forward with information it's like a ray of light."

An RSPCA inspector is already hunting the Norfolk cat killer.

When animals are poisoned - as with most of the cats in Harleston - the key is to track down the "bait station", Evans says. In a similar case, he came across a piece of chicken floating in a poison made from a common household product. His task was then to prove that the chicken was put in intentionally as bait.

In 12 years he estimates he's brought about the convictions of a dozen people. Most crimes are unsolved.

He remembers the case of a greyhound found close to death on a mountainside, having been shot in the head with a stun gun. Evans managed to track the dog down to an unlicensed racetrack in the area, where staff put him in touch with the greyhound's owner.

It turned out that the dog had broken its leg and the owner had given someone £10 to shoot it. The hired killer claimed to have shot it dead but had only stunned it and dumped it with a hole in its head on the mountain. The man was tried, convicted and imprisoned.

But six months in prison is the maximum sentence for animal cruelty, which some animal lovers feel is insufficient. Sir Terry Pratchett, who has offered a £10,000 reward for catching whoever is behind the Somerset swan killings, believes the law is too lenient for serious animal cruelty.

"People who do this sort of thing to an animal are probably a danger to people as well. I don't think the punishment will fit the crime," he said.

For Evans the outcome of the greyhound case was a "triumph", which makes the painstaking work worthwhile. "These people aren't normal - the anger and malice they exhibit can be disturbing. When you go to court and the person gets sent to prison it's fantastic."

The motive for animal killings is often not clear, but one category of deaths is often attributed to disgruntled farmers and gamekeepers. The RSPB's most up-to-date figures reveal that in 2009 32 birds of prey were shot and 81 poisoned.

Whatever species is involved, the tenacity of investigators pursuing culprits despite a lack of evidence remains the same.