King Arthur and Camelot: Why the cultural fascination?

- Published

- comments

A new television series is the latest dramatisation of the Camelot myth. But why is the legend of King Arthur such a compelling one in culture?

For a man who may or may not have wandered Britain some 1,500 years ago, King Arthur retains the enviable knack of making his regal presence felt.

Merlin, Excalibur, Guinevere, Lancelot, the Lady in the Lake - all the components of his story are instantly familiar both in his erstwhile homeland and in much of the world.

Modern historians might query whether there is any real evidence for his existence, but none doubt his lasting hold over the popular imagination.

His, after all, is a tale that takes in romance, heroism, chivalry, honour and, of course, the promise that its hero will one day return to rescue his people.

Channel 4's adaptation is the latest in a very, very long line

Little wonder, then, that the entertainment industry continues to cheerfully plunder it.

Camelot, a Channel 4 drama starring Eva Green and Joseph Fiennes, is only the latest in a series of big-budget takes on Arthurian legend. Recent years have witnessed the 2008 BBC series Merlin, 2007's Colin Firth blockbuster The Last Legion and 2004's King Arthur, starring Keira Knightley and Clive Owen.

Nor is this a recent fad. No less a Hollywood icon than Indiana Jones was confronted by Arthur's mythology in his third big-screen encounter, while John Boorman's 1981 fantasy Excalibur and Robert Bresson's 1972 film Lancelot also re-imagined the saga.

Perhaps most memorable of all, however was 1975's Monty Python and the Holy Grail, with its less than reverent take on the story - ("strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government").

What all demonstrate is that somehow, over time, the story of a fifth or sixth-Century Romano-Celtic warrior resisting Anglo-Saxon settlement became the basis of one of the West's most treasured chronicles.

Academics have attempted to identify contemporary figures on whom Arthur may have been based, and his name appears as a military commander in Nennius's 830AD account History of the Britons.

However, most experts agree that the story was popularised by the 12th Century History of the Kings of Britain, written by the Oxford-based Welsh scholar Geoffrey of Monmouth.

According to Geoffrey, his work was based on a secret lost Celtic manuscript to which only he had access. It told of Guinevere, Merlin, the sword Caliburn - later known as Excalibur - and Arthur's final resting place in Avalon.

The historian Michael Wood, who explored the Arthurian sagas in his books In Search of England and In Search of Myths and Heroes, regards Geoffrey's work as, essentially, pro-Celtic propaganda, based on a desire to mythologise Britain's pre-Saxon heritage rather than verifiable fact.

But ultimately, he believes the veracity or otherwise of the legend is irrelevant - more important being the grip it has held on the collective imagination ever since.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is not rock solid history

"These myths have the power to get recycled by different cultures because they are great stories," says Wood.

"They suggest there was this golden age of lost innocence. They are still living stories that connect with people. He gets appropriated by everybody. It's endlessly repeatable - the hero fighting the dark, evil hordes."

Certainly, the story of Arthur developed a life of its own after Geoffrey's account became the medieval equivalent of a bestseller.

The French writer Chretien de Troyes introduced the Holy Grail to the story as well as Lancelot, who cuckolds Arthur.

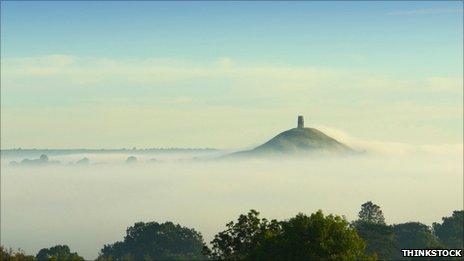

In 1191, monks claimed to have discovered the remains of Arthur and Guinevere at Glastonbury abbey. Though latter-day cynics have observed that the building had recently suffered a fire and an influx of tourists would have been of great assistance to the restoration fund, the find cemented the area's status as the focal point of English mysticism and crystal healing shops.

Through this process, over time, Arthur transmogrified from a fierce Celtic warlord to a wise, noble and honourable national father-figure.

Terry Jones, co-director of Monty Python's interpretation of the myth, and a keen historian, says he was always cynical about the Arthurian legend and its supposed virtues for this reason.

But nonetheless, he says he recognised that the universality of the tales made them an ideal backdrop for Pythonic humour.

"The ideas of chivalry are very suspicious," he says. "The reality of the time was of men clad in armour going around beating up undefended people. The whole notion of chivalry was about dressing it up to make it respectable.

"But when we did the Holy Grail we knew it was a good story that everyone recognises. Everybody tries to claim Arthur for themselves - the French and the Welsh, not just the English."

Indeed, Nick Higham, professor in Early Medieval and Landscape History at the University of Manchester and an expert in Arthurian myth, believes the sagas help us chart the development of national identity on these islands.

Although Geoffrey of Monmouth presented Arthur as a Celtic hero, Prof Higham says, this legend was, in turn, appropriated by the Normans, who found the notion of a noble, pan-British, non-Anglo-Saxon hero politically useful.

Arthur represents chivalry, mysticism, Britishness and men whacking each other with swords

Likewise, he says, the Tudor dynasty appropriated Arthur on the basis of their Welsh heritage. And in the early 20th Century there was an upswing of interest as contemporary analogies were drawn with a British hero fighting invaders from Germany, Prof Higham argues.

"Because there's nothing known about Arthur in reality, he's incredibly malleable and you can present him however you want him," he says.

"As the consequence of a series of peculiar accidents, Arthur has been portrayed as the solution to our cultural problems down the ages."

Romantics may hope that, one day, Arthur will return to rescue his people.

But if he lives on through his legend, the ancient monarch, it would appear, has never really gone away.