Spies like us: How defectors come in from the cold

- Published

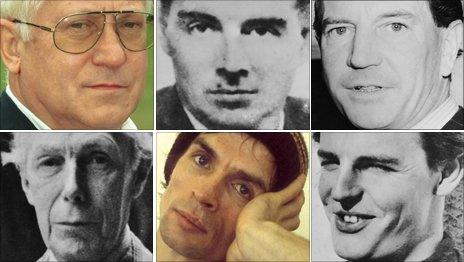

It is 60 years since British spies Burgess and Maclean sensationally fled to the Soviet Union. But how do defectors adjust to their new lives?

You have spent years in the half-light, betraying those closest to you. And now your secret is out.

Spirited away to the foreign power you covertly served all along, you know you can never return to the homeland that now reviles you as a traitor.

With your loyalties out in the open, you must make a life for yourself in your adopted nation. How?

In June 1951, the press was filled with speculation about the whereabouts of two missing British diplomats, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, who had disappeared the previous month.

The pair, it would later transpire, were in the Soviet Union, having fled from their imminent exposure as double agents passing state secrets to Moscow.

These two urbane, upper-middle-class Englishmen - part of the notorious Cambridge Five spy ring - would now have to adjust to life in a regime they had idealised as a workers' paradise.

It was not a task for which both men were equally suited.

Maclean assimilated enthusiastically into communist Moscow, establishing himself as a European security expert whom his colleagues affectionately nicknamed Donald Donaldovitch.

Burgess, however, proved less adaptable. As depicted in Alan Bennett's television play An Englishman Abroad, he slumped into lonely alcoholism, scarcely bothering to learn Russian and continuing to order his suits from Savile Row. He drank himself to death aged 52.

Their contrasting experiences raise the question of how a defector should go about constructing a new life.

Despite the end of the cold war, defectors are, after all, back in the news.

After Col Gaddafi's foreign minister and former spy chief Moussa Koussa defected to the UK, Foreign Secretary William Hague urged other Libyan officials to follow suit, promising they would be "treated with respect" in Britain.

There can even be defectors within a country. A group of 17 leading Libyan football figures, including the nation's goalkeeper, and three other national team members, recently announced their defection to the rebels within Libya.

One adopted Briton in a position to offer defectors guidance is former KGB Colonel Oleg Gordievsky, who worked for MI6 as a double agent for 11 years until he came under suspicion from Soviet authorities in 1985.

Gordievsky had been based at the USSR's embassy in London when he was ordered back to Moscow on a pretext and interrogated. But, in an astonishing escape which rivals any episode in espionage fiction, he managed to reach the border with Finland and was smuggled across by British officials.

Feted for his daring as well as the invaluable information he provided, Gordievsky settled happily into life in the Surrey commuter belt. He wrote a series of books and articles and, he says, felt gratified to be welcomed into London's intelligence and literary community.

Indeed, such was his familiarity with UK customs - he had been posted to London in 1982 - and the length of his service for MI6, he dislikes the label "defector". Gordievsky insists he had been British all along.

But he admits that his first wife, Leyla, did not share his motivation to embrace his adopted country. Their marriage collapsed after she managed to join him in the UK.

"I had no problems because I was friends with British people for 11 years," he says. "I was used to British culture and the British way of life.

"But my wife, who joined me later - she had problems and had to go back to Russia because she couldn't find balance in her life in Britain.

"I was very happy to be in Britain, British culture."

Indeed, both ideological commitment and a sense that one continues to be useful to one's adopted country appear to be crucial to sustaining defectors in exile.

The journalist and historian Phillip Knightley met Kim Philby, another of the Cambridge spies, shortly before his death in Moscow in 1988.

The Soviet authorities had never entirely trusted Philby and denied him the senior KGB post he had been expecting.

As a result, Knightley recalls him as a broken, pathetic figure, pining nostalgically for "Colman's mustard, the Times, the crossword and English cricket".

But what Knightley believes kept Philby, who did not live to see the collapse of the Berlin Wall, going was his unswerving Marxist-Leninist views and his conviction that he had done the right thing.

"All of the defectors I have ever met complained about the way they were treated - they didn't feel they had enough recognition, they didn't feel they were properly compensated," Knightley says.

"If you are told you have got to live in a place for the rest of your life, you are bound to be discomfited.

"You are cut off from your previous life completely. You have the stigma of being a traitor for the rest of your life."

Not all highly-prized defectors, of course, have been spies. When the ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev fled the USSR for France in 1961, according to some sources, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev personally signed an order to have him killed.

And on the other side, host governments have an incentive to keep their assets in good spirits - whether or not they are defectors.

According to Prof Keith Jeffery, the official historian of MI6, intelligence agencies are haunted by the memory of Peter Wright. The former MI5 officer revealed the secrets of the service in his book Spycatcher after becoming disgruntled with his pension arrangements.

As a consequence, Prof Jeffery argues, agencies are keen to make sure that anyone under their care still feels important.

"There's a marketing dimension to it," he says. "They do put a lot of effort into keeping [defectors] happy because they hope this would encourage others to do the same.

"It's very important to keep them happy. While they're happy they'll tell you stuff."

It seems defectors, like the rest of us, just need to feel wanted.