Bobby Fischer: Chess's beguiling, eccentric genius

- Published

Three years after his death, interest in chess genius Bobby Fischer shows no sign of waning, with a new documentary film about to have its UK premiere. So what is it about the controversial and eccentric chess star that fascinates, asks David Edmonds, co-author of Bobby Fischer Goes To War.

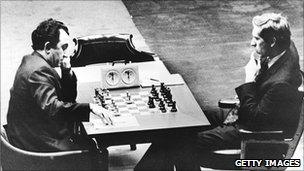

It's difficult, now, to imagine the excitement generated by the 1972 world chess title match in Iceland between the Russian champion, Boris Spassky, and the American challenger, Bobby Fischer.

There were other big stories jostling for newspaper column inches at the time. It was the beginning of the Watergate scandal that would eventually compel President Nixon to resign. Henry Kissinger was shuttling around continents seeking a truce in Vietnam. There were riots in Northern Ireland. Idi Amin expelled Asians from Uganda. The Munich Olympics were about to take place.

But much of the world was gripped by a chess match - the so-called Match of the Century - a match that Fischer eventually, and dramatically, won. The match made stars of TV presenters. It was covered by both broadsheets and tabloids. The Daily Mirror trumpeted one of Fischer's victories with the headline, Spassky Smashki.

When one reporter went from bar to bar in New York to see what their television sets were tuned to, he discovered that 18 of the 21 were showing the chess, and only three to the baseball game that the punters would normally have demanded.

What can explain this phenomenon? Why did a cerebral board game suddenly become all the rage? And why, half a century after first coming to prominence, does Bobby Fischer still exert such a hold on the public imagination?

The political context of his greatest triumph still resonates. The match happened at the height of detente. But the media portrayed Fischer v Spassky as a Cold War clash.

This was understandable. The Soviets had dominated chess since World War II. They used chess as a propaganda tool, as proof of the superiority of communism over capitalism. They had a highly efficient chess structure that identified talented players young, and trained them intensively. They believed that the world championship title was rightfully theirs.

The set-up in America, by contrast, was amateurish. There was negligible state support or business sponsorship of the game and the prize money in tournaments was meagre. Fischer was seen as a lone individual taking on the power of the Soviet machine.

Fischer played in a controversial rematch in 1992

It was a depiction Fischer himself bought into - he was going to "teach those commies a lesson". Those two months in Reykjavik were full of drama - at one stage the Soviet team accused the Americans of using chemicals and "electronic devices" to influence Spassky. When a lighting fixture was examined all the Icelanders found were two dead flies.

Even to those outside the chess world, Fischer was a baffling, beguiling, infuriating personality. Most wanted to judge him either mad or bad - he fitted the romantic image of genius perfectly.

He had been attracting notoriety from a young age. At tournaments he complained about the lighting, noise in the audience, the size and shape of the chess board and pieces. He made incessant demands for increased prize money - and usually forced concessions.

Wrangling over gate receipts almost caused the Fischer-Spassky match to be abandoned and only when a British businessman stepped in to double the prize money did Fischer finally agree to participate. Twice before Fischer had dropped out of international chess for extended periods - so the organisers in Iceland were reluctant to call his bluff.

And it's too easy to overlook the appeal of the chess itself. It's no exaggeration to say that Fischer was one of the greatest chess players in history. He had a delightfully clean and direct, style - its beauty lay in its relentless efficiency.

He calculated at extraordinary speed, but neither sought, nor shied away from complications. Always, he fought to win, whether with the white or the black pieces. En route to challenge Spassky, the Fischer juggernaut seemed unstoppable and he accomplished the unthinkable - winning 20 games in a row against elite grandmaster opposition.

Soon after Fischer was crowned world champion, he became a virtual recluse, vanishing from view, and failing to defend his title against the young Soviet, Anatoly Karpov in 1975.

Fischer was regarded as the world's greatest by many

In 1992, he reappeared in Serbia and Montenegro, to play Spassky for a $5m pot. It was in the midst of the Yugoslav war, and the match contravened international sanctions.

The mercurial American won again, but from that moment on, he was a wanted man. Every now and then there would be a sighting of him, or he would pop up on a foreign radio station - ranting and raving, spewing poison.

On 9/11, after planes flew into the World Trade Center, costing thousands of lives, he appeared on Filipino radio and declared the news "wonderful". "Death to the US", he said. His violent anti-Americanism was matched by an equally virulent anti-Semitism - though he himself was of Jewish origin.

He was finally picked up in Japan in 2004 - he kicked and screamed and it took many men to hold him down. He might have been extradited to the United States had Iceland - the country he'd put on the map in 1972 - not offered him honorary citizenship. He died there four years later.

Bobby Fischer made chess sexy - or as sexy as chess can get. Neither before nor since the 1972 showdown, has chess seemed quite so exciting.

Fischer didn't enjoy the limelight. But the more he shunned publicity, the more the Fischer legend grew. And it shows no sign of abating, even after his death.

David Edmonds appears in the documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World, which is released in the UK on 15 July.