Speaking Clock: Why are people still dialling for the time?

- Published

- comments

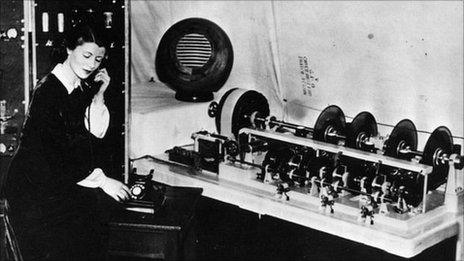

Ethel Jane Cain, a Post Office exchange operator from Croydon, was the first voice of the Speaking Clock in 1936

At the third stroke, the Speaking Clock will be 75 years old. But why in an era of laptops and mobiles do many people still get the precise time from a recording of a well-spoken woman?

Time is inescapable - it's there in the flick of a wrist, push of a mobile phone button and glance at a computer screen.

You could argue there is no real need to pick up a landline and dial 123 to hear BT's Speaking Clock and be charged 31p for doing so.

But the service still receives 30 million calls each year, with demand peaking on four very time-sensitive days.

People want to celebrate New Year at precisely the right time, they like to double check when the clocks have gone either forward or backward, and they want to ensure they start their two-minute silence at exactly 11am on Remembrance Day.

Anecdotally, it is also rather popular just before five o'clock, when call-centre staff are desperate to avoid picking up a 20-minute call from an irate customer.

The Speaking Clock was created for people who did not have a watch or clock to hand. Before 1936, people used to ring the exchange operator, a real person, to settle a dispute over the time.

The original Speaking Clock and two subsequent models were developed by the Post Office in the UK, although one was sent to Australia.

The Post Office had a long history of helping people set their clocks when many places still operated on local time, says Viscount Alan Midleton, curator and librarian at the British Horological Institute. This was before the railways made it essential for everywhere to be operating on the same time - set as Greenwich Mean Time.

"In the large Post Offices in cities, they had very accurate clocks and the mail coaches would set their watches by that," says Viscount Midleton.

"Using the old solar measurements, Bristol was 11 minutes behind Greenwich and Penzance was 20 minutes behind. When the mail coach arrived a large number of people would gather around the coachman - who was like a walking Hello magazine - and get the political gossip and the official city time.

"It is thought to be the origin of the phrase 'passing the time of day'. They were literally getting the time of the day and the gossip."

British obsession

The first Speaking Clock was accurate to within one tenth of a second and its modern equivalent is accurate to within five thousandths of a second.

For everyday things, such as catching a train, making a doctor's appointment or getting to school on time, that level of accuracy is unnecessary.

But when even seconds are precious, it can be frustrating when your phone is displaying one time and your computer another.

The Speaking Clock is still an emblem of accuracy to some people, which might explain why they're still prepared to pay for it, says Rory McEvoy, a curator of horology at the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

In 1936, when the speaking clock was introduced, people were reliant on mechanical clocks, says McEvoy.

"Mechanical time-keepers are reliable to a point. They are prone to inaccuracy because they can get dirty and need considerable maintenance.

"The Speaking Clock was a way of being sure you had the correct time, and the English had an obsession with precise time keeping."

He says it is still relevant today because our modern electronic gadgets are not always great time-keepers - as if to prove his point, his own computer was running four minutes late.

The Speaking Clock gets its time from the atomic clocks at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), the UK's official time-keeper.

The clocks keep the time accurate to within one second in three million years, which means the error in a day or a week is minuscule.

While precise time is vital to keep the internet running and for satellite navigation, the NPL's Peter Whibberley says it isn't much use to the average person.

"For most people it doesn't matter if their clock or watch is off by a few seconds but the error has to be corrected before it becomes too large.

"Many clocks are simply free-running and gradually drift away from the correct time of day. Others are reset regularly to a reliable source of time."

His reliable time sources include the national radio time signal operated by NPL, which provides the time pips on the radio, and internet time servers.

"The best way to get the most precise time is probably to use a GPS receiver, which should be able to obtain the correct time to better than a microsecond or a millionth of a second. GPS chips are now often found built into the latest generation of mobile phones," he adds.

But of course, accuracy is not the only reason why people are still calling the Speaking Clock.

"Brian Cobby, the third voice of the Speaking Clock, used to receive fan mail from people who used the service late at night just to hear his calm voice," says McEvoy.

Sara Mendes da Costa became the fourth voice of the Speaking Clock in 2007, triumphing over 18,500 other entrants.

She says back then about 70 million calls were being made to the Speaking Clock. People of a certain generation were brought up on it, she says, but younger people may not be aware of it.

"It's something I remember from my childhood - it was the first call I ever made. It's steadfast. People trust the Speaking Clock - Big Ben is timed by it."

She says the previous voices were incredibly well-spoken but BT were looking for a "voice that was a little bit more now".

"In the past, it was frightfully, frightfully and very clipped. They were looking for a voice that people trust, a warm and friendly voice."

Like McEvoy, she also thinks precise time, rather like the weather, is a British obsession.

"I'm certainly a bit obsessed with being on time. My father drummed it into me that I had to be home at 11pm and not a moment past."

Scientists and engineers might need the precise time, but these childhood memories of the value of punctuality may be what sustains the layman's passion for exactitude.