The time when the British army was really stretched

- Published

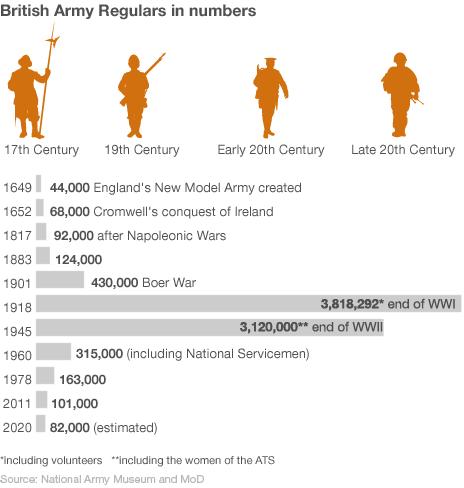

The British army is due to be reduced to 82,000 by 2020, prompting claims it will be the smallest it has been since the 19th Century. But if Britain had a small army then, how did it control an empire?

Think of the British army during the late 19th Century and you might conjure up images of Zulu or Carry On Up The Khyber.

Considering the British Empire at its peak included a quarter of the world's population, one would imagine the army was more like Michael Caine and Stanley Baker (from the former) than Kenneth Williams and Sid James (from the latter).

But the British Empire managed to maintain hegemony over dozens of colonies with a relatively tiny number of men.

Defence Secretary Liam Fox announced this week he planned to cut regular army numbers to 82,000 - 120,000 in total including the Territorial Army (TA) - by 2020. It was widely reported this was the smallest it had been since the Boer war.

But according to the National Army Museum, that's not the case. Julian Farrance, from the museum, says the regular army (not including reserves) numbered around 124,000 men during the First Boer War in 1880-81 and was actually much bigger by the time of the Second Boer War in 1899-1902.

So has the army ever been smaller than it will be in 2020?

The British Empire's expansion into Africa was driven by traders like Cecil Rhodes

"The first regular army - the New Model Army [of England] - was created by Oliver Cromwell and it grew in size from 44,000 to 68,000," says Farrance.

The army kept growing throughout the 18th Century (as the British army after the acts of union of 1707) and after the Napoleonic Wars it fell to 92,000 in 1817, before growing again as the British Empire expanded.

But Michael Codner, head of military science at the Royal United Services Institute, says Britain has never had a large army.

"What we needed was the Royal Navy and a system of indigenous constabularies overseen by a small but professional British army," he says.

Military historian, Dr Huw Davies, from King's College London, points out India was garrisoned by hundreds of thousands of locally-recruited sepoys, supervised by fewer than 30,000 British troops.

"The empire had to pay for itself and had to be profitable and if you put too much into building up the army the empire is no longer a profitable enterprise," he says.

The empire suffered occasional setbacks, such as the Indian Mutiny of 1857, defeat by a huge Zulu force at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879, external and the humbling at the hands of an Afghan army led by Ayub Khan at the Battle of Maiwand the following year.

Around this time the Cardwell Reforms, external - initiated in the wake of the Crimean War - modernised the regimental system, abolished the buying and selling of commissions by officers and banned flogging during peacetime.

But how was an empire controlled with such a small force?

One of the British Army's darkest days - outnumbered and defeated at Isandlwana

"It's often thought the British army in the 19th Century just mowed down natives with a machine gun. This is a myth," says military historian Nick Lloyd.

"The most remarkable thing is that they often had no technical advantages and we managed it by spending only 2.5% of GDP on defence, which is not much higher than we have today.

"We mainly won through teamwork, logistics and organisation," Lloyd says, adding that cunning diplomacy was often used to rule parts of Africa and India.

In recent years the newspapers have been full of articles in which senior military figures, or retired grandees, argued the armed forces were "overstretched".

But this is nothing new, says Lloyd, who works at the Defence Academy.

"[In the 1900s] Lord Roberts campaigned for greater spending on defence. He claimed we were overstretched and needed to spend more to keep up with the likes of Germany and bring more troops back to protect the home country. The Boy Scout movement was part of this movement to train more soldiers."

Another echo of the past is the army's role in Afghanistan today.

"In the 19th Century we spent a lot of time training the Afghan army, which is identical to the situation we have now in Afghanistan," says Dr Davies.

"We didn't want to annex Afghanistan as a colony, but just to have it as a stable buffer zone to prevent the encroachment of Russian agents trying to destabilise India. It was all part of The Great Game."

In the 19th Century the embarrassment of military defeats at Khartoum and Isandlwana respectively helped bring down the governments of both Gladstone and Disraeli.

By the time of World War I the army, boosted by volunteers and the creation of the TA in 1908, contained almost four million troops and almost as many during World War II.

The figure dropped significantly in the 1940s, with hundreds of thousands of demobbed men returning to "civvy street". As the empire withered away the numbers slowly shrank, but the next significant fall was in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War.

So, as history shows, the success of an army is not just about its size. A small but professional force has often served Britain just as well. But one thing that never changes is the need for good organisation and leadership.