When suicide was illegal

- Published

- comments

Up until 50 years ago suicide was a crime in England and Wales. But why were people prosecuted for attempted "self-murder" and how did things change?

When police found Lionel Henry Churchill with a bullet wound in his forehead next to the partly-decomposed body of his wife it is hard to imagine the emotional turmoil he must have been in.

He had tried but failed to take his own life in the bed of their Cheltenham home.

Doctors said the 59-year-old needed medical treatment at a mental hospital, but magistrates disagreed. In July 1958 he was sent to prison for six months after pleading guilty to attempted suicide.

His story made just a few column inches in the Times, but in the newspaper's archives his tale is far from uncommon.

Take out-of-work labourer Thomas McCarthy, 28, who "drank something bad" on the steps of St Paul's Cathedral after becoming depressed. He was sent to prison for a week for his troubles in October 1923.

And then there is Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey Walker 48, of Heathfield, Sussex, who in June 1953 was fined £25 for attempting suicide with a French revolver he found on a beach at Dunkirk.

The penalties for attempted suicide varied from a fine to a short spell in prison

And 31-year-old William Morgan, of Islington, north London, who tried to take his life in an elaborate way involving a van, was sent to jail for a month in February 1959.

Nowadays it would seem almost unthinkable to punish someone for attempting suicide, but until just half a century ago, it was a crime in England and Wales.

A Times leader on the subject noted that in 1956, 5,387 failed suicide attempts were known to police, and of those 613 were prosecuted. Most were discharged, fined or put on probation, but 33 were sent to prison.

"If they were hauled in front of a court for attempting to kill themselves, or even worse sent to jail, I can't even begin to imagine the impact of that, and the stigma (that followed) would have been horrendous," says Dr Caroline Simone, senior lecturer and expert in suicide bereavement at Derby University.

Some were shown leniency, like Lancashire man Harry Howard, 27, who tried to take his own life because he didn't want to spend the night in a "cold" police cell, and Mabel Sayers, 37, of Dartford, who, in a sudden "fit of depression" turned on the gas and gathered her three children around her.

World-weary hangman John Ellis, who turned a gun on himself, was also spared. "If your aim had been as true as the drops you have given it would have been a bad job for you," the chairman at Rochdale Police Court told him as he was discharged. "Your life has been given back to you, and turn it to good use in atonement."

Night-time burial

"Self-murder" became a crime under common law in England in the mid-13th Century, but long before that it was condemned as a mortal sin in the eyes of the Church.

For a death to be declared a "Felo de se", Latin for "felon of himself", an old legal term for suicide, it had to be proved the person was sane.

If proven, they were denied a Christian burial - and instead carried to a crossroads in the dead of night and dumped in a pit, a wooden stake hammered through the body pinning it in place. There were no clergy or mourners, and no prayers were offered.

But punishment did not end with death. The deceased's family were stripped of their belongings and they were handed to the Crown. "The suicide of an adult male could reduce his survivors to pauperism," Michael MacDonald and Terence Murphy wrote in Sleepless souls: Suicide in early modern England.

In many countries suicide was never criminalised. And in some cultures it was seen as a patriotic alternative to dishonour.

It is thought that Greek philosopher Socrates became his own executioner - sentenced to death by drinking poison - and in ancient Athens it was said city magistrates kept a supply of poison for anyone wishing to die. In Japan, Samurai warriors would carry out Seppuku, a ritual suicide by disembowelment, rather than fall into enemy hands.

"Attitudes to suicidal behaviour have changed over time and at different times in different places," says Prof Nav Kapur, head of research at Manchester University's Centre for Suicide Prevention.

'Shockingly slow'

So why was suicide punished as a crime in England and Wales until 1961?

"We were one of the last European countries to decriminalise suicide - we were way behind our European counterparts," Dr Simone says.

"We have been very slow and the punitive action that someone's possessions could be forfeited to the Crown up until 1822 is shocking really."

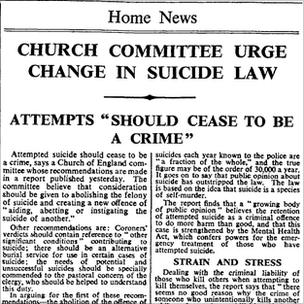

A report in the Times from 20 October 1959

But Dr David Wright, professor of history at Canada's McGill University, says prosecutions were "rare" taking into account the tens of thousands of hospital admissions for suicidal tendencies.

"Sometimes it takes a long time to change legislation because it really isn't that relevant anymore," he adds.

Unlike the high profile cases that have peppered the assisted suicide debate in recent years, experts say there was no significant campaign for a change in legislation. Instead came a gradual realisation that the laws of the day were at odds with society's view, and that care not prosecution was needed.

"From the middle of the 18th Century to the mid-20th Century there was growing tolerance and a softening of public attitudes towards suicide which was a reflection of, among other things, the secularisation of society and the emergence of the medical profession," says Dr Wright, co-author of Histories of suicide: International perspectives on self-destruction in the modern world.

In 1958 the British Medical Association and the Magistrates' Association urged a "more compassionate and merciful outlook", and a year later the Church of England joined the calls for change.

The Times also campaigned, drawing attention to the fact that suicide was not a crime in Scotland. "Attempted suicide seems to have become punishable in England almost by accident," a leader stated in 1958.

However as late as 1958, home secretary of the time Richard Austen Butler seemed unconvinced. "Although it is clear there is greater sympathy and understanding for suicides, there is no evidence that an alteration would be universally acceptable to public opinion," he told the Commons.

But St Pancras North Labour MP Kenneth Robinson, who raised the issue in the Commons many times, would not let the matter drop.

On 27 February 1958 he tabled a motion contending that suicide should cease to be a criminal offence. Within days 150 MPs had signed it.

When the law was finally repealed three years later it was widely welcomed and 50 years on it is still seen as an important moment.

"What was happening in the late 50s and early 60s was that attitudes shifted from suicide as wrongdoing or sin to the medicalisation of suicide, recognising that the majority of individuals attempting suicide or dying [from suicide] were in a great deal of distress," says Kapur.

Despite a much more sympathetic attitude, experts say there is more to be done.

A YouGov survey commissioned by Samaritans shows a third of 1,066 people polled would not talk to someone, external if they felt suicidal.

Clare Wylie, the charity's head of policy and research, says it shows many still consider suicide a "scary or taboo topic".

It is clear debate over attitudes to suicide will go on, but how far could we be from another change in the law?