England riots: What are the Post-it note 'love walls' all about?

- Published

- comments

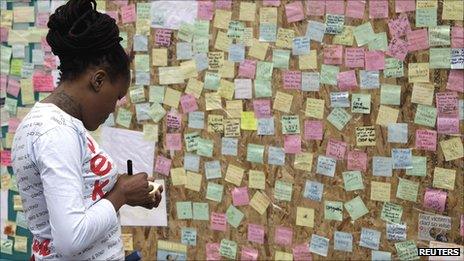

After the riots, thousands of people chose to express their feelings on Post-it notes, covering "peace walls" or "walls of love" everywhere from Manchester to south London. Why?

Within hours of rioters ransacking shops and setting buildings ablaze in Peckham, hundreds of multi-coloured Post-it notes declaring their love for the place were stuck to the windows of its smashed-up Poundland store.

Like the residents brandishing brooms at Clapham Junction's clean up, people seemed determined to create some kind of antidote to the violence. But even with the riots over, the Post-it note phenomenon is still flourishing.

In Manchester's Arndale shopping centre, which was targeted by rioters, hundreds of residents are having their say every day. Locals estimate the number of notes could be as many as 4,000. Peckham's Poundland is already on its third wall - with the council promising to preserve the "impromptu outpouring of pride and respect" in its local library.

Lynsey Saker says it was important to post a message to show the community that people cared

The sticker sensation has also spread to Crystal Palace in south London, and Tottenham, where the riots started. At Clapham Junction's looted Debenhams, where people have penned their points on wooden boards rather than notes, there is barely space left to share a thought.

So who is posting the messages, and what do they hope to achieve?

Rowenna Davis, a councillor in the London borough of Southwark, which includes Peckham, says the spontaneous "wall of love" was "about the silent majority expressing themselves in colour, words and community - rather than violence and destruction".

"It was quite cathartic for people to know that other people felt the same, that they were not alone, that people loved their community, and there was pride in the area."

Davis's messages included "Peace in Peckham", "I'm so proud", and "Let's keep joining hands".

Another sticky note advocate is 35-year-old advertising manager Lynsey Saker, who has lived in south-east London for four years.

She says her friends went out in Crystal Palace armed with them "in order to show the community that we will repair it, we will rebuild it, but most importantly that we care about it".

"It upset me to see shops vandalised, I know how much passion people put into their businesses, this is a lovely community, it was a way of expressing how we felt, of showing we appreciated them," she says.

Dr Martin Farr, a contemporary historian at Newcastle university, says it is not the first time Post-it notes have been used in this way, pointing to their use after 9/11 and the 2004 tsunami.

But he says although they were predominantly used in a different manner then - to try and locate missing relatives - there was also a sense of messages being used for people to come together and communicate, or just be physically present at a significant place.

"In a way, it harks back to the old notion of a central town hall, where people went to see notices, it's reverting to a pre-modern way of coming together," Dr Farr says.

"There was also a similar thing at the deaths of John Lennon, Amy Winehouse, or Princess Diana for example - whether it was wine bottles, flowers or messages, there was a kind of urge for people to physically turn up to share or express their emotions."

Dr Farr says there was a contrast with the violence.

"New media seemed to facilitate or characterise the rioting, what struck me is writing notes is very old media, it's as if it's a restatement of community identity.

"It's also an old-fashioned, a human way of seeing handwriting - with smileys and exclamation marks - so is different to new media which is technically consistent. Post-it notes are also very photogenic, they are appealing - from a distance they are almost like an impressionist painting of a garden - so they are an engaging way of communicating," he says.

Design critic and cultural commentator Stephen Bayley agrees that the use of "low-tech" Post-it notes is significant as "the robbers abused sophisticated smartphones".

"Charming, sentimental, concerned, non-destructive, clever, responsible and recyclable, these Post-it messages represent very different values to those so atrociously revealed last week.

"We hear a lot of nonsense about 'public art' which is usually ham-fisted and out-of-touch. Here is authentic public art - engaged, engaging and unforgettable."

The public nature of the Post-it note profusion is something psychologist Geoff Beattie also thinks is highly relevant.

"The riots were very public, so the public counteraction is a critical aspect of this. Our environment has been redefined and reshaped - human beings use visual markings to claim areas - so people are partly reclaiming their streets by putting down a territorial element," he says.

He also thinks people also undeniably gain some form of comfort and solidarity from the communal action - which implicitly encourages others to participate.

'Positive vandalism' has been used throughout all areas of London

"I was watching people put up Post-it notes in Manchester, and what struck me was their body language. It was almost like the way people sign up to an anti-cruelty manifesto, there was a sense of 'I'm prepared to do this, come and join in'," he says.

The sticky notes are the most transient form of graffiti, being removable in a matter of minutes. And Beattie says he was struck by how simple the messages were.

"They weren't profound, it wasn't like that - they said things like 'I love Manchester, I love the city centre' rather than trying to write anything poetic - which suggests to me that the sheer number of Post-it notes is the commonality, the critical communicative dimension."

Ellis Cashmore, professor of culture, media and sport at Staffordshire University, believes the Post-it note movement will continue for some time.

"I would not be surprised if it has longevity, not so much out of people paying their respects but as a promissory note - a way of saying they will do everything they can to prevent it happening again," he says.