Why do so many disabled people embark on dangerous feats?

- Published

- comments

A new documentary with Prince Harry follows four wounded servicemen on a trek to the North Pole. But why do so many disabled people embark on adventures that most "able" people wouldn't even think of doing?

The foursome accompanying Prince Harry to the North Pole includes Steve, who had his back broken, and 26-year-old Jaco, who is missing part of an arm.

They are far from being the first injured ex-servicemen to test their new bodies when faced with a disability.

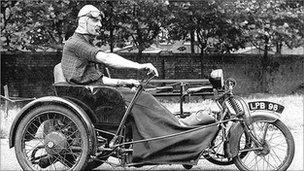

In 1947, Denny Denly, who became a wheelchair user after contracting polio while on active service, fancied a holiday in Switzerland. He rode 1,500 miles across the French Alps on a petrol-powered tricycle with a top speed of 30mph.

His journey, which involved climbing to 8,000 feet (2,440m) through mountain passes, was documented by the BBC Home Service. Public reaction to the trip was so positive it led to the launch of the Invalid Tricycle Association, a precursor to today's Disabled Motoring UK.

Left blinded and with part of a leg missing by a landmine in WWII, climber Syd Scroggie refused to be daunted and completed 600 ascents.

Slow and steady: Denny Denly in 1947

"Whatever we call the hills, it has nothing to do with sight," he once said. "It is an inner experience and can be as poignantly savoured with your eyes shut as open."

It's not just ex-servicemen. All flavours of disabled person seem drawn to pushing themselves way beyond what's called for in their daily routine.

Dave Heely, who went blind at 18, has just completed 10 marathons in 10 days, while travelling between each one on the back of a tandem. That's 750 miles of cycling and 250 miles of running, from John O'Groats to Lands End.

Myles Hilton-Barber, also blind, is arguably the best known disabled adventurer in the UK. He lost his sight at 21 but didn't start his career in adventuring until he reached 50. He now travels the world making a living as a motivational speaker.

He has completed an 11-day ultra-marathon across China from the Gobi Desert to the Great Wall. He became the first blind pilot to undertake a 55-day, 13,000 mile (21,000km) microlight flight from London to Sydney, using a talking navigation device.

Hilton-Barber believes that conquering these incredible feats of human endurance has changed his perspective on what it means to have a disability.

"Before I started doing this, I thought I needed sight to be happy. Now I realise it isn't about focusing on what you can't do, it's saying what you want to do and then figuring out what you can achieve. I always wanted to be a pilot."

But not all disabled people feel the need to test their physical and mental limits, says disability activist and campaigner Barbara Lisicki.

"I will never be able to climb a mountain or trek across the jungle but I don't care. In the disability arts and culture world we call this phenomenon 'supercrip syndrome'.

"Disabled people doing things that non-disabled people struggle to do and that's what makes them great. Most of us are actually fine the way we are and don't feel the need to prove ourselves."

The need to climb a huge mountain isn't something that comedian Francesca Martinez, who has cerebral palsy, can relate to.

"I'm too lazy to do something like that," says Martinez, who was asked to take part in the BBC adventure programme, Beyond Boundaries, but declined.

"I told them, if you have a show called 'lying on the beach in the Caribbean, call me'. My goal every day is to eat three big meals and to get at least 12 hours sleep."

When Denly was driving his trike, disability unemployment was high and those who were in work often held posts in sheltered workshops or similar enterprises. Even today, 70% of blind people of working age are unemployed.

So is taking on adventures a substitute for lack of success in life against ordinary measurements?

Heely believes that his adventures, and the media coverage they create, have helped prevent him becoming a statistic.

"I was made redundant from a sales role in the early 90s and being blind, I knew I wouldn't have a chance of getting another similar job. It is thanks to my challenges that I've become a motivational speaker, working in schools.

"Each time I take on a new adventure and get some publicity off it, it gives me another couple of years employment."

Newspapers regularly carry stories about disabled people pushing their broken bodies to the extreme.

Hilton-Barber believes that media attention is an important motivator for disabled adventurers. He says disabled people who see other people with disabilities pushing the limits are inspired to fight for a new sense of identity.

"It gives them status. Disability robs you of your confidence. I lost my dignity, my independence, but I can jump out of a plane and people will have respect for me."

But Lisicki has her own theories on why the media relish these stories.

"The press is always happy to focus on the old tragic but brave stereotype. Earlier this year, 5,000 disabled people marched against government cuts. This got very little media coverage, because people find looking at a collective of disabled people uncomfortable.

"It's much easier for them to focus on one individual and say 'aren't they marvellous?'"

But whether it's for the love of adventure, to prove that disability is no barrier or, as Jaco from Harry's Arctic Heroes says, "to bring back the feeling of being able to do something again", the disabled adventurer phenomenon is bound to continue.