Should animals be stunned before slaughter?

- Published

- comments

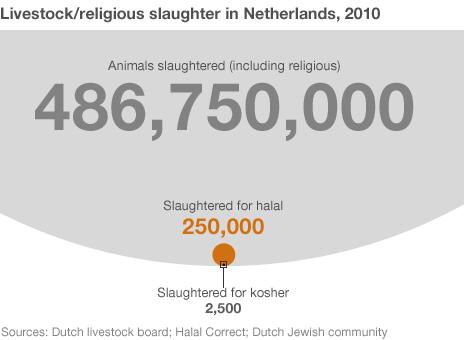

The slaughter of conscious animals was widely abandoned in the 20th Century and is now practised mainly in the Jewish and Muslim communities. Consumers increasingly expect animals to be stunned before death - but would banning other slaughter methods be an unacceptable violation of religious rights?

The sound of pistons and mechanics fills the air as the last calf of the day steps into a holding box.

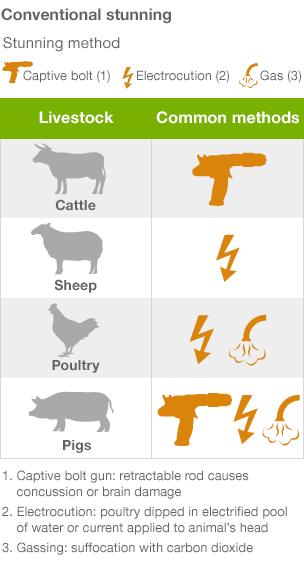

A device the size of a hand-held drill is brought to the animal's head, a trigger pulled and a four-inch bolt shot into its brain, causing it instantly to collapse. The unconscious calf is hoisted upside down and slaughtered seconds later with a massive cut to its throat, showering the floor with a torrent of crimson blood.

"Killing animals is never friendly," says Paul Meeuwissen, director of the Vitelco abattoir in the central town of s'-Hertogenbosch, "but what we do is done in the most animal-friendly way possible."

The plant - the second-biggest veal abattoir in Europe - has used stunning on all its calves - some 300,000 a year - since 2008. Before then it performed some religious slaughter without stunning for the Jewish and Muslim communities, but changing public attitudes towards animal welfare forced a rethink.

The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe, external took the position in 2002 that "the practice of slaughtering animals without prior stunning is unacceptable under any circumstances", and the issue has gradually become more central for animal welfare campaigners, and for politicians.

"We decided to stop 'ritual' killing because the idea didn't fit us," says Mr Meeuwissen. "My customers are very critical on how we produce our meat, and the large supermarket chains no longer want any meat which is produced ritually."

In the Netherlands and elsewhere, most of the remains of an animal slaughtered by the Jewish method (shechita) end up on supermarket shelves as regular meat products, because parts of the carcass are forbidden to Jews under their dietary laws.

Marianne Thieme, Party for Animals: 'If you have humane techniques you should use them'

But if these parts of the animal are not sold, the operation becomes less economically viable.

Later this month, a bill that would effectively ban the slaughter of unstunned animals goes to the upper house of the Dutch parliament.

Sponsored by the Party for the Animals, it has already been approved in the lower house, where it was backed by the anti-Islamic Freedom Party and opposed only by the Christian parties, which took a stand in defence of religious freedom. Most observers expect it to become law.

'Friendly for humans'

Jewish and Muslim leaders see a worrying global trend, with the Netherlands a critical test case.

They are fighting a battle on two fronts - to dispel the idea there is anything inhumane about their traditional methods of slaughter, and to defend their right to live according to their religious beliefs.

Both faiths put great emphasis on animal welfare, and adhere to a one-cut method of slaughter, intended to ensure the animal's rapid death.

Under Jewish and Islamic law, animals for slaughter must be healthy and uninjured at the time of death, which rules out driving a bolt into the brain - though some Muslim authorities accept forms of stunning that can be guaranteed not to kill the animal.

"What I think is that stunning is friendly for the human being and our way of slaughtering is friendly for the animals," says Motti Rosenzweig, Holland's only Jewish slaughterer (shochet).

Under shechita, the animal's neck is cut with a surgically sharp knife, severing its major arteries, causing a massive drop in blood pressure followed by death from loss of blood. Supporters say unconsciousness comes instantaneously - the cut itself stunning the animal. A similar procedure is used in Islamic slaughter, or dhabiha.

"In one second - maybe two if it's a bull - the animal is gone," says Mr Rosenzweig, who trained for years in Israel and now slaughters once a week, under the observation of a state veterinary official, at the Amsterdam Abattoir.

"In my opinion [conventional] stunning is torture. Just because it can't say 'moo' or move anymore, it's very nice for the human eye, but the animal is alive and the scientists don't actually know if it's suffering or not. If I have to make my choice, my choice is clear."

Chief Rabbi Benjamin Jacobs: 'I believe our method of slaughter is friendlier to animals'

A Dutch Muslim umbrella group, the Contact Body for Muslims and the Government (CMO), accused the Party for the Animals of leading an "emotional" campaign based on misleading information which "wrongly created the impression that Muslim and Jewish methods of slaughter are barbaric and outdated".

"They use the words 'ritual slaughter' but there's nothing ritual about it," says Dutch Chief Rabbi Benjamin Jacobs.

"It's not dancing around a cow, it's a method, but by using the word 'ritual' a lot of people are getting very upset."

Scientific dispute

Positions on religious slaughter vary around the world - in the US, for instance, it is specifically defined as a humane method in the Humane Slaughter Act (1958) - but elsewhere several countries have already restricted or banned slaughtering unstunned animals.

Stunning has been obligatory in the European Union since 1979 in order to spare animals "avoidable pain or suffering", though most member states make exceptions for religious communities.

A study of the issue commissioned by the Dutch government, external in 2008 concluded that "ritual slaughter has a number of negative aspects for the animals when compared to conventional procedures where a stun is performed prior to slaughter".

Its findings were mirrored in a 2010 report by a consortium of scientists for an EU-funded project, which concluded that "it can be stated with the utmost probability that animals feel pain, external during the throat cut without prior stunning".

It said research showed most cattle seemed to lose consciousness between five and 90 seconds after the cut, and were sometimes subjected to "potentially painful manipulations", including follow-up cuts, while still conscious.

Both reports, though, have been dismissed as flawed by Jewish and Muslim groups, who argue that the research was done by scientists opposed to religious slaughter to begin with.

"It is still unproven that slaughtering with stunning is a better method," says CMO chairman Yusuf Altuntas.

In the case of shechita, Jewish authorities say no investigations of the issue in Europe have actually involved the first-hand study of animal slaughter by a trained shochet using a chalef (shochet's knife), which differs from an ordinary abattoir knife in shape, length and sharpness.

"One has to assume that these people have a political agenda and it comes through time and time again in Europe," says Dr Joe Regenstein, an animal slaughter expert at Cornell University in the USA, who is preparing a report, external for the Dutch Jewish community to challenge the slaughter bill.

"They are going in there with what I'd call a scientific enlightened secular religion that says stunning must be better than unstunned slaughter."

In contrast, Dr Bert Lambooij of Wageningen University, a co-author of the Dutch report and consultant in the EU-backed project, says the evidence against religious slaughter is clear.

"There are some scientists who are unconvinced, but they haven't done the research," he says.

One scientist who has observed closely the work of trained shochets is Dr Temple Grandin of Colorado University, a renowned expert on the humane treatment and slaughter of livestock.

Her verdict is that conventional slaughter with preliminary stunning, and religious slaughter without stunning, are both acceptable when conducted properly.

"There's good and bad stunning but the research shows very clearly that when you stun an animal properly with a well-maintained captive bolt, unconsciousness is instantaneous - it's like turning off a light switch," she told the BBC.

"Similarly when I've seen shechita on a cow done really right by a really good shochet, the animal seemed to act like it didn't even feel it, external - if I walked up to that animal and put my hand in its face I would have got a much bigger reaction than I observed from the cut, and that was something which really surprised me."

Religious fears

Animal rights groups see the Dutch bill as a stepping stone towards further bans on religious slaughter.

"The Netherlands is a very important example, but for us it's just a battle, not the war," says Dr Michel Courat of Eurogroup for Animals, a federation of animal protection groups.

"We need to win lots of other battles after this one to make sure more countries stop this practice."

This is the big fear among Europe's Jewish and Muslim communities.

"We're afraid that other countries in Western Europe will follow the Dutch example," says Mr Altuntas.

"We heard from our Muslim council partners in Germany, Belgium and France that parties there are watching it closely and are preparing to take a position."

If the Dutch bill becomes law, Jewish and Muslim leaders say they will fight it in the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that it is a violation of the right to freedom of religion.

"If the Party for the Animals proposed a law which said there shouldn't be any slaughtering of animals any more and everyone should be vegetarian, I could understand it better," says Rabbi Jacobs.

"But it's a vote against religion. The new religion is anti-religion and people get fanatical about this. What worries me is what might come next."