The myth of free wi-fi

- Published

- comments

A council leader in Swindon has come under pressure after the town failed in efforts to offer free public wi-fi. So why doesn't the UK have more free wireless internet?

Sitting on a high street, you suddenly realise you need to log on to read an urgent email. You flip open your laptop and you're happily greeted by a long list of available wireless networks.

Then the hoop-jumping begins.

Enter a password, input an access code, purchase a card, buy a latte - it all becomes a massive hassle and you realise a truly free open network is as rare as hens' teeth.

These days, city centres are flooded with hurried business people anxious to access email and make important deals en route to their next meeting.

Then there are tourists, students and a host of other people, all of them eager to get maps, buy things and carry out other myriad tasks.

When it comes to wi-fi access overall, the UK is at the front of the global pack.

A recent study by the Office for National Statistics showed that 4.9 million people connected through hotspots such as hotels, cafes and airports over the last year in the UK, up from 0.7 million in 2007.

But there's a catch. These hotspots usually either come with a charge or require you to be a customer - buying a superfluous sandwich or grudgingly grabbing a grapefruit juice in order to get your internet hit.

Wi-fi provider The Cloud serves many cafes and restaurants, including Pizza Express, Eat and Pret A Manger - but users must be ready to eat.

And BT recently announced a partnership with Heineken pubs where wi-fi is on the house - starting with 100 pubs in London and expanding to 300 throughout the UK by 2012. But again, you have to be a customer.

Many councils have realised the potential benefits of community wireless access and tried to launch free wi-fi schemes. Many have failed.

London's Islington Council installed a "wireless mile", an area through the borough equipped with free public wi-fi, but access ended as cuts set in.

Probably the most trumpeted example was in Swindon, which aimed to have free wi-fi emanating from the top of lampposts for the whole town by April 2010. A loan was made to a private provider, but the money ran out and private sponsors were hard to come by, the council says.

Now only one small section of the town is covered.

But while councils and other bodies have struggled in the UK, there are many successful free wireless internet projects around the world.

Many US cities - including Denver, Raleigh and Seattle - have free access in some areas, usually the centre. Bologna in Italy has a similar set-up.

Taipei in Taiwan currently has major public sites covered, but much of the city will be covered by October.

The whole of the city of Oulu in Finland is covered, in a partnership with a number of local universities. Its backers say not only does it improve communication, but it is a useful tool for Oulu's online government services.

NYCwireless is a non-profit organisation that builds free public wireless networks in parks and open spaces in New York City, including a newly announced outdoor space covering the area between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges.

"We thought: 'What if we can bring the internet to the beautiful spaces in New York City'," says Dana Spiegel, the organisation's executive director. "We bring wireless to everyone and keep people from being chained to their desks."

There is some progress in the UK.

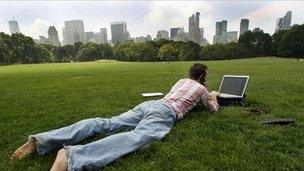

Free public wireless internet is an amenity in many New York City parks

Bristol has a free and open network in much of the city centre. The council says this is done at minimal cost because decades ago they purchased old cable ducts allowing them to create their own broadband network.

In 2007, the City of London initiated "free" wireless access, touting its importance for traders, bankers and brokers to access data on the move - but only the first 15 minutes are actually free.

Virgin Media plans to roll out free public wi-fi in London to compete with BT's Openzone - the catch being that customers must subscribe to Virgin's broadband service at home to access the fastest speeds at no cost.

Of course, there would be many people who would question the need for free public wi-fi, even in city centres. We don't expect free electricity or free public transport, so why should people get free internet?

But the advocates see it as a move that could stimulate business and provide a boost to quality of life.

"You don't have to have a Cadillac service with all the bells and whistles," says Dailywireless.org tech blogger Sam Churchill. "But it's a basic requirement these days, just like water and power in a civilised society, that helps people communicate and keep informed."

But the powers-that-be can't seem to agree on whether funding of any sort should go to free wi-fi, particularly in these straitened times.

In Islington's case, spending cuts led to funds being targeted on core services like adult social care, and the free wi-fi scheme stopped working in March 2011.

"Wi-fi is not something we would put money into," says Kulveer Ranger, an adviser to the London mayor on all things digital. "We put money into things with a direct application to public service, like transport."

And this attitude is why some people say the private sector is a more viable route.

"Enabling the private sector to accomplish this goal is preferable to taxpayer funded efforts," Churchill says. "Make it free for everyone."

For now, most Britons will have to brace themselves for the occasional wi-fi rigmarole.