Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: John Le Carre and reality

- Published

The new film adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, premiered at the Venice Film Festival last week, has been praised for its atmospheric depiction of 1970s London. But how firmly is John Le Carre's novel rooted in reality?

(Spoiler alert: Key plot details revealed below)

Trying to establish the precise relationship between John le Carre's fictional depiction of British intelligence in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and real life is a task that requires the investigative skills of George Smiley.

And even le Carre's fictional spymaster might be left wondering if he had unpeeled all the layers of mystery to get to the real truth.

It is not unusual for writers to draw on the real world and their own experiences and then shape it into fiction. But le Carre is different. He draws on his own experience of the secret world for his work.

And because that world - and le Carre's own career in it - is out of sight and clandestine, the reader is left wondering, far more than usual, where fact ends and fiction begins.

"He has traded in this ambiguity through his career and made a virtue of it," argues Adam Sisman, who is currently engaged in the challenging task of trying to establish the truth for the authorised biography of le Carre.

Le Carre's work was always coming from a different direction than Ian Fleming's James Bond books. Fleming's creation was a Technicolor escapist fantasy, le Carre's rooted in a grey, complex and morally ambiguous reality. No-one considers Bond to be real (well, almost no-one). But le Carre's world is different. It feels authentic.

(Warning: Reading on from this point will spoil the plot for anyone who has not seen the film or original TV series or read the book)

Some of his novels fit closely to what we know of le Carre's own life and career in the secret world, most notably A Perfect Spy.

On the broadest level, Tinker Tailor too is rooted in a very real and traumatic period for British intelligence.

Le Carre served in MI5 and MI6 in the 1950s and early 1960s and these were troubled times. It was becoming clear that the British establishment had been subverted from within. A small group of people - many motivated by the struggle against fascism in the 1930s and 40s - had begun secretly working for the Communist cause and had burrowed their way into the establishment.

Amalgam characters

Their treachery was being exposed just as le Carre was coming of age as a writer. Burgess and Maclean, two diplomats, fled to Moscow in 1951. By the early 60s, the rot had been found within British intelligence itself, with George Blake and Kim Philby exposed as traitors.

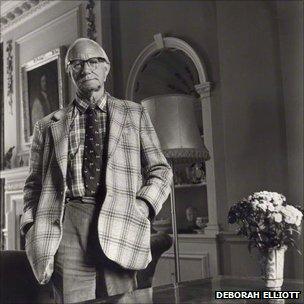

The "spiritual" model for Smiley: Le Carre's chaplain at Sherborne School and Lincoln College Oxford

Was that the full extent of it? A defector, Anatoly Golitsyn, arrived in the West talking of more traitors. Was another still in place? How high up might he have reached? The investigations would consume British intelligence in the 1960s and into the 1970s with even the head of MI5, Roger Hollis, coming under suspicion.

In le Carre's fiction, the traitor, Bill Haydon, bears a close resemblance to Kim Philby, with his easy charm, good social connections and rise towards the top. Beneath the surface lies an antipathy towards the establishment of which he is part and the country which he serves. In an earlier draft of the book, there were reported to be more similarities to Anthony Blunt, another of the Cambridge Spies.

But in the final draft, the fit between Haydon and a real person, in the form of Philby, is quite close, while other characters are more of an amalgam.

What of George Smiley? The search for the real life inspiration of the man hunting the traitor is complicated. Some thought he resembled a real chief of MI6, Maurice Oldfield. But this is more a result of the 1979 TV adaptation of Tinker Tailor. Alec Guinness, who played Smiley, was introduced by le Carre to Oldfield over lunch and adopted some of his mannerisms.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy has premiered at the Venice Film festival

"I still don't recognise myself," the spy chief wrote to the actor after seeing the programme. Many others did though.

But the TV series came several years after the written version of Smiley. There are two other more likely influences. One is the Reverend Vivian Green whom le Carre knew as a schoolboy and then at Lincoln College, Oxford. Another is John Bingham (later Lord Clanmorris), an MI5 officer who worked with le Carre and who wrote fiction himself.

"Bingham was the physical inspiration for Smiley and Vivian Green the spiritual inspiration," reckons Sisman.

Rabbit warren

Tracing Karla - Smiley's nemesis - is also harder. Some have suggested Markus Wolf who ran the East German Stasi but when the theory was floated past le Carre, he dismissed it as wrong. While other spymasters, such as Rem Krassilnikov of the KGB, would be later described as a real-life Karla, it is not clear who was the original inspiration for the character.

The Circus? 90 Charing Cross Road fits Le Carre's description - but it was never MI6's headquarters

Language is another area where disentangling fact and fiction in Tinker Tailor is possible, but challenging. Some of what le Carre uses is real, some made-up and in some cases the made-up has become real.

"Some of the terms have come into parlance thanks to Le Carre," argues Sisman. "Life has imitated art."

The Circus - le Carre's headquarters for MI6 based in Cambridge Circus, in central London, is fictional. In reality, MI6 was based at Broadway Buildings in St James' Park, a rabbit warren of old rooms, before it moved to Century House south of the River Thames, with its grey post-war linoleum floors (an appearance that some who worked there once told me was closer to a building in the Soviet Union).

Sarratt, the fictional training school for British spies, is actually a village near Watford in which le Carre worked as a teenager in a department store, says Sisman. The real training establishment is known as "The Fort".

Control - used to refer to the head of MI6 - bears only a little relationship to reality. The man who headed the service was and is known as C. Beneath him there are Controllers - for instance for different geographical areas (Controller - Asia for instance).

The name C originated with the first head of what would later become MI6, Mansfield Cumming, who signed documents he had read with the letter C, penned in green ink. Later directors have also been called C, but it is said to stand for "Chief" rather than "Control" (they still use the green ink though).

Frisson

Not all former spies liked le Carre's depiction of their world. "John le Carre I would gladly hang draw and quarter," Baroness Daphne Park, a former MI6 officer, told me shortly before she died.

Others were less sure that his fiction was such a problem. "There were those who were furious with John le Carre because he depicts everybody as such disagreeable characters and they are always plotting against each other," Sir Colin McColl, a former MI6 chief told me.

"We know we weren't always as disagreeable as that and we certainly weren't plotting against each other. So people got rather cross about it. But actually I thought it was terrific because it carried the name that had been provided by Bond and John Buchan. It gave us another couple of generations of being in some way special."

The secret world may be the wellspring of his fiction but le Carre has worried over what he should and shouldn't reveal.

For former spies there is always the fear of being accused of spilling real secrets. "It's a matter of pride to me that nobody who knows the reality has so far accused me of revealing it," le Carre once told me when declining a request to be interviewed about his work on the BBC.

What many of his readers enjoy though is the frisson of entering a clandestine world with its own language - the sense of what it might feel like to be on the inside.

In Tinker Tailor, le Carre manages to both strip away some of the mystique surrounding spying - to reveal the human frailties and petty bureaucracies - but also to envelop British intelligence in a new shroud of mythology which it still has not entirely shaken off.