Upper Gereshk: The Helmand plan meets tough reality

- Published

"This place makes you old fast," one marine told me

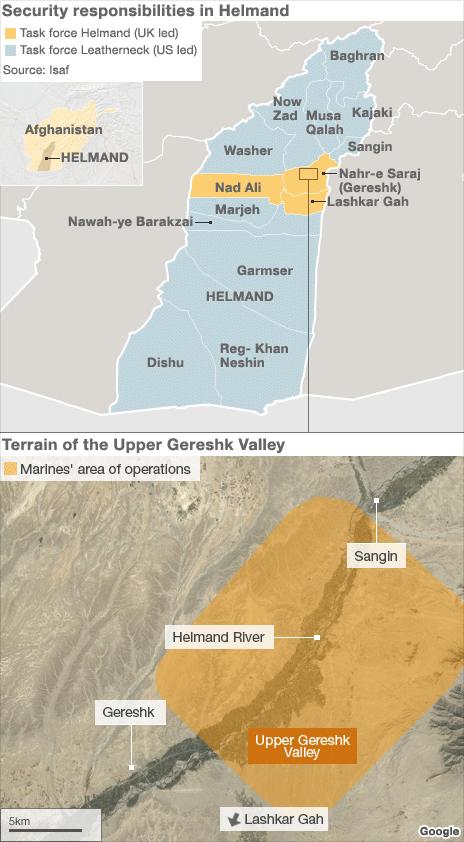

After 10 years in Afghanistan, foreign troops can claim successes in the notorious province of Helmand - but a vicious guerrilla war still rages in the Upper Gereshk valley, which US marines are in the process of handing back to British forces.

It has only just turned 07:00 and it's already pushing 35C (95F). The three litres of warm water you drank at dawn have already soaked into your flak vest.

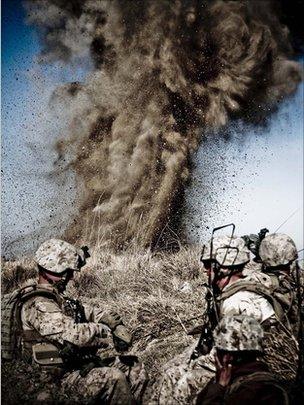

The patrol advances slowly, inching through poppy fields like their lives depended on it. Suddenly a massive explosion rips through the air less than 50m behind. The Taliban have booby-trapped the right-hand gate of the compound with a grenade and an IED (improvised explosive device) during the night. By chance we exited by the left gate.

"Well good morning to you, too," grunts a marine.

Twenty-one-year-old Dustin Weier picks himself up and leads with a metal detector sweeping this way and that, followed by a dog handler with a black Labrador called Moxi. Both are there to detect the countless other IEDs buried just inches under the dry, lumpy soil, and they're not always successful. The patrol follows directly in their footsteps, a safe path indicated by baby powder or bottle-tops placed on the dirt.

"Straight line 10 yards until you get to the bottle-top, then turn and come directly to me," the message is whispered from one man to the next down the line. To deviate a few inches could result in a pressure-plate being compressed and the baritone boom of 20kg of silvery-grey homemade explosive exploding underfoot.

It's happened twice in the last four days, three times if you count that near miss. Around here that makes it a good week.

The sun is beginning to burn as the patrol pushes 150m across an open field when the Taliban open up from tree lines to the west. One marine drops instantly, shot in the lower back.

"I'm hit," he shouts as he falls to the ground.

The rest of the squad returns fire. Time compresses as a thousand bullets make an impossible noise. But instead of the insurgents ghosting away before the marines can take aim or helicopter gunships arrive, they increase their rate of fire.

Sustained, accurate gunfire rips through the patrol and the Americans are forced to retreat to safety, running through a wall of gunshots from the west that are joined by fire from the east. A well-executed complex ambush.

Sucking mud

It's the brazenness of the Taliban that is unexpected - within 20 minutes they are throwing grenades from hidden positions just a few metres from the patrol and firing others from low-slung launchers. The grenades dance towards the landing zone as a medevac helicopter lands to pick up the casualty.

The contact lasts the best part of an hour and it is not until the helicopters overhead finally open up with their missiles that the insurgent guns lie quiet.

In the silence, all you can hear is the metallic click-clack of weapons being reloaded and the song of the swallows that flit through the air.

And it's like that every single day.

The war in Helmand isn't supposed to be like this, not now. With good security gains being made in the district centres of Marjeh, Garmser, Now Zad, Nad Ali and Musa Qalah, on paper things look like they're going to plan.

On paper, 2011 is indeed a good year to start the troop drawdown and hand over partial control to the Afghan Army. But paper is never much use when you are up to your knees in sucking mud, and enemy snipers are shooting your comrades almost at will.

In the ploughed fields and thick tree lines of Upper Gereshk valley and up north to Sangin, a place where British forces lost a third of their total casualties in Helmand, the war still rages and it has caused terrible damage to the US Marines, who have been fighting an unseen and determined foe.

"This is our Vietnam," say the marines of 3rd Battalion, 4th Regiment, who by mid-September had taken 90 casualties since they deployed in April, including five killed in action.

"Every time we leave the wire we get shot at or find an IED, either with our engineers or by treading on it. The Taliban have freedom of movement and we can't engage until they've engaged us first. Sometimes it's hard to see what we're supposed to accomplish out here."

Intelligence suggest this area was home to the Afghan Army 93rd Brigade in the 1990s and that elements of this old unit form the core of the fighters here - veterans of combat, well-armed and tactically minded.

Ferocity

In a bad week, injuries are sustained almost every day.

The 2nd Platoon is just 50m outside its patrol base when it is attacked by accurate machine-gun fire. One marine is killed after four rounds hit him in a tight grouping just below the collarbone and another strikes him in the back. As his comrades scramble on top of a building to return fire, an IED placed on the roof blows up, amputating the limbs of a machine-gunner.

The marine behind him has his clothes ripped off completely by the force of the blast and suffers concussion. That platoon takes a total of six casualties in one day - the medevac helicopters clattering constantly overhead.

One day later, a marine is hit by a sniper round in the side, it bounces off his fifth vertebra and exits under his right arm. Forty-eight hours after that, the 3rd Platoon is manning a position in an orchard when a round whistles in and catches one of them directly above his bulletproof vest - one inch above his heart.

A week later, a grenade lands in the middle of a secure compound, wounding three marines on their way to dinner.

The ferocity of the Taliban attacks is such that one of the battalion's two rifle companies, Lima Company, redeployed its troops to observation posts within a few hundred metres of the company's main base.

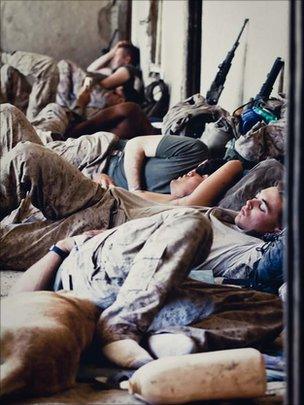

By 13:00 it's so hot nobody can move

The patrol bases a kilometre away had been abandoned, rations and supplies burned to deny them to the enemy, insurgents visible on the roofs of the compounds within minutes of the last marine leaving.

This isn't the progressive Helmand you sometimes hear about in the news.

"I see this place like Garmser two years ago," says Lt Col Robert Piddock, the Battalion Commander at Combat Outpost Ouellette.

"We expected this level of activity. Third Battalion 5th Regiment had a tough time in Sangin last deployment [the unit took more than 225 casualties] and that's where we're at now. Casualties happen, we're an infantry battalion."

The US marines had no Afghan Army units in Gereshk in support of the "clear, hold and build" strategy that has worked in other parts of the province - though the UK's Ministry of Defence says 2nd Battalion, The Mercian Regiment, which is now moving into the area, will have Afghan units alongside it.

There were also less than a handful of Afghan local police to watch the newly-built Route 611 between Gereshk and Sangin, and the men of Lima Company found themselves running out of options on a battlefield where the Taliban appeared to have the upper hand.

Taliban chatter

"I deployed here with the Royal Marines 40 Commando in 2007 and not a lot has changed," says Captain Andrew Terrell.

"The situation is no better. The people here are not fed up with the fighting, they've not reached the limit of what they're willing to accept from the Taliban. It's easier for them to move out of the area and hope it settles down, but they don't look much further than tomorrow."

An IED is discovered and exploded

In one week in May when the poppy harvest was completed, more than 300 families loaded their belongings into cars and on to tractor-trailers and drove out of the area, heading south for the security of Gereshk district centre.

"That was when we knew things were changing around here," continues Capt Terrell.

"In a little over a week, an area that had been busy was pretty much deserted. There are no village elders here now, they live in Kandahar or Lashkar Gah and they're not coming back until the fighting season is over [in October].

"The people here draw their money from the poppy harvest, and so long as that's still happening they're not too worried about what happens. And if you're dead-set on fighting, if you're that small group of hardcore Taliban, then you're going to fight and this is the place to do it."

You hear the Taliban on the radio. Every unit carries with them Afghan interpreters listening in on their communications on a transceiver. It's a strange thing, to be listening to the Taliban while they chatter all day.

Normally they spend most of their time talking about nothing, lots of hellos and goodbyes, waiting for the marines to make a move. But as soon as a patrol leaves base, their tone changes.

"The Americans are leaving, be ready to move into positions in 15 minutes," the insurgents will say. They know the marines are listening and sometimes it will be a foil. But often it isn't, and after a sustained contact you can hear the Taliban discuss their casualties over the radio.

"How many injured do you have?"

"I will call you back. It is several."

"Will we need a car to take them to Gereshk?"

"Yes."

Fighting-age males

All coalition forces in Afghanistan rely heavily on meetings with the local Afghans to gauge their concerns, ask what their requirements are, to spread the word on how coalition efforts will bring increased security to the region.

A marine rushes to help a fallen comrade

These shuras are attended by the village elders, religious mullahs and local governors. I've sat in on dozens of such meetings and they're always the same, the commanding officer asking how they can improve security and offering to build bridges, wells and other local projects to show how the coalition are a force for good in the area.

In the simplest form, if you create work then those around you will drop their weapons and pick up shovels instead.

But in Gereshk, there are no shuras to speak of. It's hard to have a meeting with the elders when everyone has left for the summer and the only people inhabiting the area now are fighting-age males.

The weekly Saturday meetings with the handful of prematurely old men with deep facial lines and hawkish features who attend are little more than convivial sit-downs with the fathers of the local Taliban. They know it, the marines know it, and the Afghans laugh among themselves, talking in circles as they often do when sitting down with foreign soldiers.

"Why is my son in jail?" asks Mohammed Sarif. Tall and with a large, round face adorned with a white beard, his eyes glisten with emotion.

"Because your son is a bad man," states the CO. "We caught him with explosives on his hand, and we have seen him laying bombs in the ground."

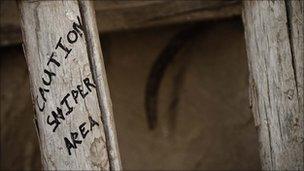

Warning on a ladder leading to a sentry point

"My son has not done these things."

"Yes, he has, and we have seen him do it."

"Then I will kill him myself."

"He will be brought to justice."

"Give us tanks and guns and we will fight for justice in our area."

"That's good, we are recruiting for local police. Get 15 men and we will give them all the training they require."

"We cannot join the police."

"Why not?"

"The Taliban would kill us."

Impasse.

"Money is not an issue," says Captain Terrell afterwards.

"We've got plenty of money we can bring to the area but since nobody cares about projects here there's little point in spending money because it won't improve the situation."

Dark humour

By 13:00 it's so hot nobody can move. Only the freshwater crabs that live in the irrigation canals venture out of their muddy holes to feed. The skies above resonate with the distant buzz of Reaper drones and the slash and burp of jet fighters on a gun run.

I ask the Battalion Commander how much pressure there is to get a "result" in this corner of Helmand.

"There is a danger that we do something here that isn't sustainable," says Lt Col Piddock.

"If Task Force Helmand take over our battlespace, they won't have the numbers we do. A counter-insurgency fight is a long road and we'll leave this place better than when we arrived, but at some point you have to start talking about leaving."

The British are now returning to the place that gave them so many nightmares in the past, and they are likely to need at least a battalion of highly motivated Afghan Army soldiers to have enough troops to secure the ground.

Lima Company got on with the job, buoyed by a ruthlessly dark sense of humour. One evening they mime to a version of The Outfield's I Don't Want to Lose Your Love Tonight on their rifles, but replacing the chorus with their own, "I don't want to lose my legs tonight."

"If I lose both legs and both arms to an IED," announces a sergeant, shortly after the platoon evacuates a triple-amputee, "if one of you bastards doesn't finish me off, then I'm going to get on my electric wheelchair back home and, using a Stars and Stripes pennant with my chin to control the joystick, drive myself out onto a freeway and finish the job."

It's so real they have to make fun of it.

The next morning 3rd Platoon make its way through thick brush to occupy a new observation post, the branches slapping at their faces, boots slipping in the mud.

The Taliban has flooded the fields to make movement more difficult, and the canals that channel water to the crops are deep and sheer sided. The engineers enter the compound first, sweeping for IEDs and booby-traps.

It's a big, solid building, high walls with room for everyone. There's a vineyard loaded with sour, unripe grapes and two fresh-water wells - an ideal platoon base.

Marines scale the walls and locate look-out points. An Afghan interpreter is helping move sandbags when a high-velocity shot cracks through the air.

"Medic!"

Not 20 minutes into a new base and already the place is zeroed by a sniper. The bullet has entered the Afghan's left shoulder and exited straight out through his back with little tissue damage, the vivid purple entry wound clearly visible below his collarbone.

The squad return fire towards the location of the shooter, firing rockets into the position and a patrol quickly pushes out to look for a body or evidence they scored a hit.

Nothing is found, no trace of the sniper, and radio chatter is heard that the Taliban have eyes on the patrol and are preparing to attack again. The war in Helmand isn't supposed to be like this, not now.

But it is.

All photographs taken by John Cantlie, who spent most of July with the US Marines in Upper Gereshk