What would Britain look like without a green belt?

- Published

- comments

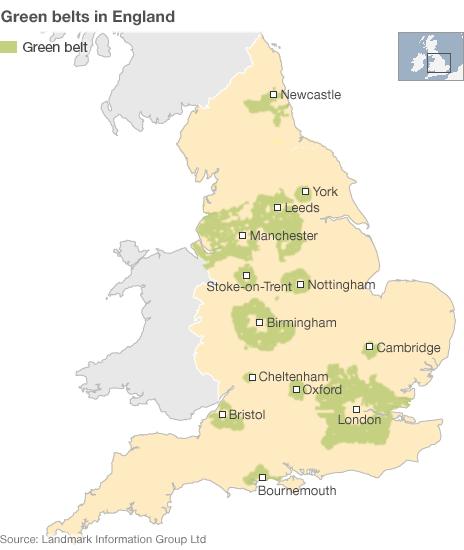

Plans to speed up England's planning process put the green belt at risk, campaigners warn. But what would the country look like without such a system?

It is, according to its supporters, the ultimate guarantee that the land is kept green and pleasant.

Encircling British cities and towns, it is more than just a set of controls and regulations - it reaffirms the British self-image as a country of rural, pastoral idylls that, in reality, the majority of Britons no longer live in.

The green belt may be a product of the 1940s, but a row over the government's proposed planning bill shows that it carries an emotive resonance that is very much alive today.

Though often misapplied to refer to the countryside in general, the term green belt refers to a specific areas of rural land where development is restricted.

For its supporters it has preserved cherished landscapes and the British way of life. Its critics claim it has hindered development, stifled growth and fuelled house price inflation.

Few, however, ask the most radical question of all - what would the nation look like if it had never been created?

Rarely, after all, has a government policy left such a visible and long-lasting mark.

"If you fly over the British countryside, you can see it," says Terry Marsden, professor of environmental policy and planning at Cardiff University and author of Constructing the Countryside.

"You're passing over settlements that are very visibly ringfenced."

Its advocates say that, without the protection it has afforded, cities like London would expand ever-outwards, subsuming smaller settlements beyond its boundaries such as Hertford and Guildford. Opponents say other European countries have managed to prevent this kind of urban creep without green belt policies.

Its spirit has been repeatedly been invoked in the debate over a proposed bill to streamline the planning system in England by creating a "presumption in favour of sustainable development", making it harder for councils to reject projects.

The government insists the green belt would be protected under the reforms. Planning Minister Greg Clark says they would strengthen rules around building on such land and give more say to local people.

But groups like the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) say the bill's proposed targets for housing would undermine the special status long afforded to 13% of English soil.

The sensitivities invoked are particularly British. All sides have been keen to stress the need to act as custodians of the countryside, protecting the landscape from US-style low-rise sprawl.

Politicians have long been aware that the notion chimes deeply with the British sense of self, and is meddled with at one's peril. During Labour's time in office, then-Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott faced regular complaints that his housing plans were a threat to the green belt.

And now ministers' fiercest critics, including the National Trust, the Daily Telegraph and a number of backbench Tory MPs, are scarcely typical of the kind of antagonists to a Conservative-led administration.

But they are reminiscent of the very movement that brought about the green belt in the first place, with groups like the CPRE lobbying during the 1920s and 1930s for safeguards against urban sprawl and so-called "ribbon" development.

In 1935 London's regional planners proposed the Metropolitan Green Belt and the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act encouraged local authorities to protect the land around towns and cities from building.

Few would question the long-lasting impact of the policy. But conservationists on one hand and advocates of development on the other disagree over its extent and whether it has been positive or negative.

The question of what the UK countryside would look like without it may be answered in the years ahead by Northern Ireland, which in 2010 replaced its green belt with a new set of planning instruments.

According to Jack Neill-Hall of CPRE, the UK's traditional communities and landscape would have been subsumed under an ever-encroaching spread of low-level development during the post-war reconstruction had there been no green belt.

"Without it, you might have ended up with an entirely urbanised south-east of England," he says.

"Our cities could have sprawled out like Los Angeles, and because there would have been no incentive to develop brownfield land the inner cities might have decayed like in Detroit."

Indeed, such campaigners say the government is not doing enough to exploit disused industrial land for new housing. According to the National Land Use Database there are 63,750 acres of brownfield sites in England, up 2.6% on the previous year and enough for more than a million new homes.

Are proposed changes to England's planning regulations a threat to the countryside?

Others are less convinced. Critics of the system point out that 9.8% of land in England is developed compared with 13.2% in Germany, a country without a green belt equivalent.

For this reason, Dr Oliver Hartwich, an economist with the Centre for Independent Studies, who has studied the British system, believes that without the postwar planning system, the UK would only "look slightly different, but not much".

Instead, he suggests the real impact of the green belt has been to fuel house price inflation and push development further into the "real" countryside beyond the green belt, leading to more commuting, fuel use and stress.

"No-one wants to concrete over the countryside," he adds. But British cities are overcrowded.

"What this sort of planning does is encourage a system where bubbles are likely. The idea that you need to get into the property market in your early 20s is very harmful but it's something that this planning system promotes."

Whichever side is correct, the debate highlights a potential disconnect among Britons who shudder at the notion of the green belt's integrity being threatened yet aspire to live in detached homes within spacious, executive-style edge-of-town developments.

But as the government is discovering, the UK's pastoral self-image is one that politicians meddle with at their peril.

Additional reporting by Virginia Brown.