Why do we still buy calendars?

- Published

The calendar sales season has begun, with 2012 editions going on sale in time for Christmas. But in the digital age, why is the paper calendar so popular?

Perhaps it hangs above your telephone, or on the fridge, or beside the front door.

It might feature your football team, or a pop star, or even a favourite breed of dog.

Your calendar might be the most low-tech timekeeping device you own. But its ubiquity within the home appears remarkably impervious to the digital age.

September marks the beginning of the calendar industry's year as manufacturers bring out their New Year editions ahead of the Christmas market.

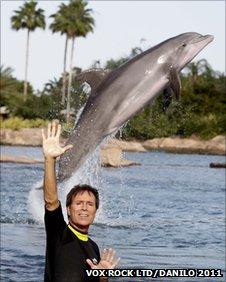

A flurry of newspaper publicity recently surrounded the launch of 2012's edition of the previous year's biggest-selling title in the UK - the official Sir Cliff Richard calendar.

Readers were treated to the latest instalment's most striking images, such as the 70-year-old playing basketball, posing in a wetsuit beneath a leaping dolphin and embracing a horse while clad in leather chaps.

The continued level of interest in this most analogue of devices is all the more remarkable given that it has, at least in theory, been superseded by technology now smartphones come equipped with personal diary planners and online calendars are available to all.

But wander through any shopping centre and it quickly becomes apparent that the traditional version remains popular.

Many of those on display feature pop stars, football teams and celebrities. Others feature household pets in a variety of heart-tugging and anthropomorphic poses.

Others rejoice in such titles as Goats In Trees, Yoga Cats and The Romance of Steam - the latter celebrating that ever-popular calendar theme, the railway engine of yesteryear.

The genre continues to evolve. Since the ladies of Rylstone Women's Institute posed naked to raise money for leukaemia research - a venture immortalised in the 2003 film Calendar Girls - the charity sector has witnessed an explosion of similar nude collaborations.

Sir Cliff Richard's calendar was a hit in the UK

Not everywhere has technology failed to dent the format's popularity. In the US, wall calendar sales were down 28% from 2005 to 2009.

But, in the UK, the product remains big business. One retailer alone, Calendar Club,, external expects to sell four million units within the UK this year.

The breakdown of its sales figures offers a fascinating insight into the shopper's psyche.

Of its customers' purchases, approximately 25% are of pets and animals, with meerkats, cats, border collies, horses and West Highland terriers among the top sellers.

Around 7% are football-related, while 27% fall loosely under the entertainment category. According to Amazon.co.uk, the current top-selling celebrity calendar is of X Factor-spawned boy band One Direction. Last year's number one, Sir Cliff, is in second place, followed by Cheryl Cole, Peter Andre and JLS.

In the US, by contrast, the 2012 title currently most in demand is a collection of inspirational slogans with the title The Power of Now.

Though the official celebrity calendar may now be ubiquitous, the notion was all but unheard of prior to 1977 when Laurence Prince, an east London printer and market trader, approached Elvis Presley's management for permission to sell the recently deceased singer's likeness above each month of the year.

The venture was a success and Prince's company, Danilo,, external grew into Europe's largest suppliers of officially licensed calendars bearing images of luminaries from the entertainment world.

Running such a business requires a great deal of forward planning, he says, with his staff having to anticipate 12 months in advance which showbusiness figures will be the biggest sellers come the Christmas peak.

However, sometimes he does not have the luxury of time. A calendar featuring Chelsea FC had to be hurriedly retrieved from the printers after Jose Mourinho's unexpected exit. And when the England rugby squad won the 2003 World Cup, a Jonny Wilkinson edition was rushed into the shops.

Despite the difficult economic climate, Prince says, sales have held solid. The proximity of Christmas to New Year means they will always make ideal gifts, he believes, and affordable ones at that.

"It think it's immortal," he says. "When e-cards came out, everyone said they were going to be the death of the greetings card business. But people prefer something physical."

Of course, many of those who continue to rely on calendars will be the elderly and the technologically averse.

But far from all of them. Technology journalist and IT consultant Adrian Mars organises his diary online. But on his wall still hangs a calendar, adorned with family photos - a gift from his sister and brother-in-law.

Even among the most digitally-up-to-date, he says, the appeal of a cardboard agenda hanging in one's home is unlikely to fade any time soon - not least because it offers a decorative function, expressing one's interests, personality and identity, that the alternative lacks.

"It's cheaper than hanging a monitor on the wall," Mars adds.

Animal calendars consistently top favourites lists

"Plus, there are practical reasons as well as social reasons that you might stick with paper. Often it's a useful way of organising a family when not everyone's on Google Calendar."

Indeed, while the ornamental and practical uses of calendars may go some way to explaining their enduring popularity, there is evidence to suggest that they are, on some level, a millennia-old expression of human instinct.

Among the earliest relics of human civilisation are believed by some scholars to be primitive calendars etched on to bone, according to Dr Paul Glennie, senior lecturer in geography at the University of Bristol and co-author of Shaping the Day: A History of Time-keeping In England.

Sumerian, Mayan, Greek and Roman societies all had their own calendars, expressions of their work patterns, holy days and culture. The invention of the printing press allowed the almanacs, which contained information about tides, likely weather forecasts and church festivals, to gain widespread popularity, Dr Glennie says.

Fundamentally, he believes, the calendar has a social function, bringing people together around a common focal point.

"It's a very flexible way of personalising something quite standard," he says. "It sounds trite, but the bit of wall above the phone would look empty without it.

"From a household point of view or a work point of view, it works on a more obviously collective level than everybody looking down at their own apps."

Millions of Britons clearly agree. Particularly, it would appear, those with a fondness for Sir Cliff.

Additional reporting by Virginia Brown