Is 'genius' a dirty word?

- Published

Extraordinary individuals: Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Ludwig van Beethoven

The annual awarding of MacArthur Foundation grants means that another 22 people are going to find themselves called "genius". But is the title a blessing or a curse?

According to the MacArthur Foundation, external, annual fellowships are awarded to outstanding individuals who show talent, originality, and dedication in all fields. They must also be citizens of, or resident in, the United States.

But due to a popular nickname, the fellows are known by a much grander moniker - genius.

The winners of the genius grants, as they're often called in the media, reflect the Foundation's broader goals. While some fellows fit the traditional idea of a genius - philosophers, physicists, composers - the grants have also gone to community organisers, journalists, and educators.

For those awarded the fellowship, the $500,000, no-strings -attached prize money is much more valuable than the honorific, a mantle most winners shrug off.

"It's a joke. Do you think if you met Plato, you would have called him a genius? If you met Socrates, would you have called him a genius?" says Ved Metha, a writer who won the award in 1982.

The disdain some winners have for the title "genius" is both a mix of humility and a sense that the true geniuses are far ahead of their time.

"When people are doing something that's really innovative, it's not recognised for a long time," says former fellow Richard A Muller, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley laboratory and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. "Most people think you're just wasting your time."

Unfathomable insight

To call oneself a genius seems like a boast. It invites unflattering comparisons to other canonic geniuses and endless opportunities for people to point out your failings.

"It's the irony between someone getting a grant for being a genius in the popular mind and the fact that any human being is likely to have done a number of stupid things," says Dirk Obbink, a professor at the University of Oxford and 2001 fellow.

Regardless of how uncomfortable it may make people, "genius" is still an often-used term.

"When people use the word 'genius,' it comes out of a mostly good place," says David Shenk, author of The Genius In All Of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ.

"They're really just admiring the tremendous and almost unfathomable insight or ability or aesthetic, or whatever other skill that someone else has that seems so far removed from their own ability."

The word does, however, have a slightly dangerous connotation.

"A lot of people use the word genius as a way to say these people were born geniuses, they have this amazing stuff inside and aren't they lucky," he says. "That's really far from where greatness comes from."

Director Julie Taymor received a "genius" grant in 1991

This tendency to conflate "genius" with "gifted" can be especially dangerous for children, who have yet to learn lessons about failure and resilience.

Calling child prodigies "geniuses" may be very damaging. "These people end up not taking risks any more, they end up sticking to what they're good at and what people are praising them for," says Mr Shenk.

"The real path to being extraordinary is risk taking and a willingness to fail. A lot of kids who are labelled prodigies early on end up being mediocre or worse," he says.

The freedom factor

For successful adults, being called a genius doesn't have the same dangerous effect - in part because they know that hard work, not lofty titles, are the key to greatness.

"In my family, it became sort of a family joke, because I don't exactly pass for a genius in my family and life," says Robert Darnton, history professor, director of the Harvard University library, and former MacArthur fellow. "I don't think my colleagues took it too seriously."

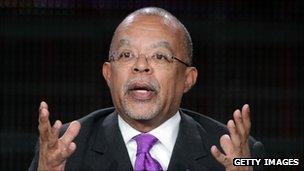

Historian Henry Louis Gates was one of the first recipients of a MacArthur fellowship

More important than the mantle of "genius", he says, was the ability to turn down teaching work to focus on his research.

"The idea of taking people of promise and allowing them to take risks is a rather good idea," he says. "In my life, it made a tremendous difference."

Giving people the freedom and security to try new things, rather than declaring them brilliant, is one of the best ways to incubate genius-like ideas and execution, says Mr Shenk.

Still, calling these men and women geniuses may have some positive effects.

"Society at large doesn't really understand the intricacies of whale echo-location or French medieval history," says Charles Bigelow, a type historian, professor, and designer who received the award in 1982.

Labelling such work the output of geniuses, however, gives the public a reason to take note. "It gives our society a way to label it, to graph it and understand it," he says. "It's a useful term - maybe not for the fellows, but for society."

Plus, as far as name-calling goes, you could do a lot worse.

"It enhances one's credibility," says Billie Jean Young, the artist in residence at Judson college and a 1991 recipient.

"You probably already thought you were pretty smart, but it's nice to have it affirmed."