Troy Davis' execution and the limits of Twitter

- Published

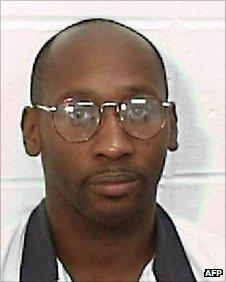

Troy Davis had been issued a stay of execution two years earlier

Georgia death row inmate Troy Davis was executed amid a massive outcry by Twitter users, who documented every minute of his final hours. Will social media change the way people view the death penalty, or will the Davis case change the way social media users view politics?

On the night Troy Davis was executed for the death of officer Mark MacPhail, thousands of outraged Americans flocked to social media to register their disgust.

Celebrities like Martha Plimpton, external and Alec Baldwin, external tweeted about the case, and Outkast artist Big Boi posted photos, external from outside the jail to his TwitPic account.

"Troy Davis", "Letter to Georgia" and NO EVIDENCE were all trending topics in the US throughout the night.

But all the angry tweets and online petitions did nothing to prevent Davis being executed at 23:08 local time in an Atlanta, Georgia prison.

Digital outrage

Public anger over death row cases has a mixed record when it comes to winning stays of execution.

In 1998, protests and extensive media coverage weren't enough to keep then-Governor George W Bush from executing Karla Faye Tucker, a confessed but converted killer.

Following a long and vocal campaign, Mumia Abu-Jamal, convicted of murdering a police officer, was ordered to receive a new hearing that could commute his sentence to life in prison. He's still on death row while that ruling is appealed.

The inability to turn the digital outrage over Davis into real-life action served as a stark contrast to the new realities of much of the digital world.

"We are living in a 21st Century communications infrastructure, but we are still governed by a 20th Century political system," says Andrew Rasiej, founder of Personal Democracy Media, which focuses on the intersection of politics and internet culture.

In an age when movies and music can be accessed instantly and a customer service issue can be resolved with a quick tweet, social media has already been cited in the success of the Arab Spring revolutions.

But the case of Troy Davis showed its limits.

"I'm not sure that 1,000 tweets or Facebook posts have the same power as one phone call," says Brian Southwell, a professor at the University of North Carolina.

He says: "We've lowered the bar for activism. Now it's a click away."

That's a bad thing, according to some on Twitter, who saw the last-minute pleas on Davis' behalf as too little, too late.

"To the people yelling injustice for Troy Davis, where were you last month, six months, years ago & not just the week prior to his execution?" asked one such tweet, external.

'Elite' power

In fact, the changes that have come to America's execution rates - which have dropped by 50% since 1999 - don't always come about due to the force of public will, registered online or otherwise.

"Some of that is reduced worry about crime and lower levels [of] homicide, and some of that is fiscal austerity," since death penalty cases are more expensive to prosecute, says Franklin Zimring, law professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Davis' death sentence generated protests both online and off

Also important is the opinion of "elites" who make a lot of decisions about how the death penalty is enacted - judges, prosecutors, and the American Legal Institute, who initially wrote the guidelines for death penalty legislation, only to publicly denounce them in 2010.

Thanks to the concerns of this group, "the death penalty is in trouble," says Zimring, despite the fact that overall public opinion for the death penalty remains strong.

A 2010 Gallup poll shows that 64% of Americans support the death penalty for someone convicted of murder, down from 65% in 2006 and 68% in 2001.

Cynicism or confidence?

To some, the realities of how the system works may be jarring. "If this is your first introduction to politics, and having grown up with [social media] as a way to express yourself, there is going to be a wake-up call," says Prof Southwell.

That could lead to cynicism, or it could lead to an evolution of younger Americans working towards a more sophisticated bridge between online activism and real-life change.

For now, the impact of social media in the Troy Davis case shouldn't be entirely discounted.

"With social media, a lot more people heard about the Troy Davis case than they would have before this existed," says John Blume, professor of history and director of the Cornell University death penalty centre.

"Maybe they didn't know about the case and weren't involved in the efforts, but a lot more people now know what happened, and perhaps the increased awareness will have a corrosive effect on support for the death penalty down the road."

Meaning this: by the rules of instant communication, social media failed. People tweeted, posted, and forwarded, but Troy Davis was still executed.

But in the much less satisfying long-term, the burst of internet activity served as a tiny push in the glacial slog of evolving public policy.