A Point of View: Churchill, chance and the 'black dog'

- Published

- comments

The wartime prime minister's dark moods, plus a series of lucky encounters, may have transformed the course of human history, writes John Gray.

Towards the end of his long life, when he was staying in a house lent to him by friends in the south of France, Winston Churchill sent for a young man who was helping him write one of the books with which he occupied his retirement.

Churchill needed the young man as a researcher. But he also valued him as a companion, particularly in the evenings when he would otherwise feel lonely.

One cold night they were sitting before the fire, where pine logs were hissing and spitting as they were burnt away. Churchill watched the blaze in silence. Then he growled: "I know why logs spit. I know what it is to be consumed."

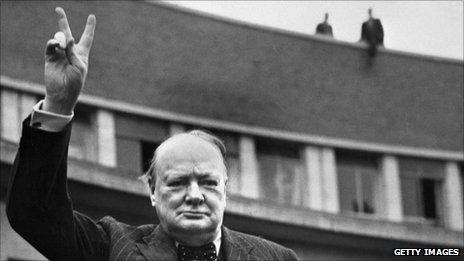

Churchill had not one life but several. Each was full of challenge and excitement, and in one of them he changed the history of the world.

Yet there were times when he felt his life had been futile, and the mood of despondency that had sometimes come upon him in his most active years - which, following Samuel Johnson, Churchill called the "black dog" - seems to have been with him in much of his later life.

But in a strange conjunction of events, it may have been this same black dog - together with the intervention of a loyal friend during a few fateful days in early May 1940 - that enabled Churchill to achieve the position from which he could alter the course of history.

There have always been those who think Churchill's recurring melancholy could have been a symptom of mental illness. Some have suggested he may have suffered from bipolar disorder, experiencing frequent mood shifts from intense bursts of impulsive activity to paralysing depression.

Nowadays we tend to interpret any type of character or behaviour that departs from our standards of tepid normality as a symptom of some underlying disorder. Churchill was certainly not tepid. He was passionate, volatile and intensely emotional in much of his life. That did not make him unbalanced.

Churchill's exceptional openness to intense emotion may help explain how he was able to sense danger that more conventional minds failed to perceive.

For most of the politicians and opinion-makers who wanted to appease Hitler, the Nazis were not much more than a raucous expression of German nationalism. It needed an unusual type of mind to see that Nazism was something new in the world, a radically modern movement with a potential for destruction that had no precedent in history.

A recent study by an American psychologist maintains that Churchill's insight was related to his episodes of mental ill-health. We needn't accept the diagnosis, but it's hard to resist the thought that the dark view of the world that came on Churchill in his moods of desolation enabled him to see what others could not. He owed his foresight of the horror that was to come to the visits of the black dog.

But Churchill's foresight would have counted for nothing if he hadn't become prime minister in May 1940. For Churchill himself, this may have been a matter of fate. Though not a religious believer, he seems to have felt that his life was ruled by a kind of destiny in which he was being prepared for a supreme trial.

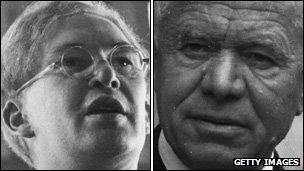

Bracken (left) and Beaverbrook were, arguably, instrumental in securing Churchill's rise to power

So it proved to be, and yet from another point of view his becoming prime minister when he did was the work of chance. Churchill became Britain's leader through the intervention of someone who is now practically forgotten.

Brendan Bracken was a strange, self-invented personality, who achieved success as the publisher of the Financial Times and the Economist and served as Churchill's minister of information during the war. Born in Ireland, Bracken grew up in Australia - where his father was a builder - before migrating to England, where he effaced his modest past and became Churchill's confidant during the inter-war wilderness years.

Bracken hero-worshipped Churchill, and supported him when the world had written him off. But the greatest service Bracken performed was in making it possible for Churchill to take power.

We tend to view the past as if it could not have been otherwise, but for Churchill to replace Neville Chamberlain in 1940 was a highly improbable turn of events. Almost no-one who counted wanted Churchill as leader. The press baron Lord Beaverbrook, who also played a role in securing Churchill the premiership, wrote: "Chamberlain wanted Halifax. Labour wanted Halifax... The Lords wanted Halifax. The King wanted Halifax. And Halifax wanted Halifax."

Beaverbrook was exaggerating. Chamberlain took a long time before deciding to resign, and it's not clear that Halifax did want to become prime minister. What is undoubtedly true is that a great many influential people wanted Halifax to take over, and it is highly likely that he could have been persuaded to do so.

Crucially, Churchill seems to have shared the view that Halifax (then foreign secretary) would be Chamberlain's successor. Churchill took for granted that he would serve under Halifax as minister of defence, and made it clear he felt it was his duty to serve in this way.

We may never know the exact pattern of events over the days of 9 and 10 May 1940. Beaverbrook liked to dramatise his role, and the accounts left by others conflict in some of their details.

But according to Bracken's biographers, he anticipated that when Chamberlain decided to resign he would arrange a meeting in Downing Street from which Halifax would emerge as next prime minister.

Loyal to Churchill and an enemy of appeasement, Bracken was determined to prevent this outcome. So at about 01:00 on the morning of 9 May, he and Beaverbrook set out to talk to Churchill, eventually finding him brooding alone in one of his clubs.

They warned Churchill of the coming meeting, with Bracken urging Churchill to say nothing if asked whether he would serve under Halifax. In the end, Churchill was persuaded to remain silent.

As Bracken anticipated, a meeting was held at Downing Street later that day, and when the issue of the succession came up Churchill did what he had promised - he said nothing.

After a long pause, Halifax said that his position in the Lords would make it difficult for him to be prime minister. Next morning, news arrived that Hitler had invaded Belgium and Holland, and in the afternoon Churchill went to the palace to tell the King he was forming a government.

Some historians have suggested that Churchill's silence may not have been decisive. If Halifax had become prime minister, they argue, Churchill would still have been in charge of the war.

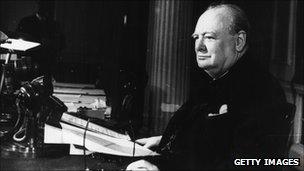

The "black dog" may have prepared Churchill for the desperate struggle against Hitler

But Halifax would have sued for peace - that was the reason so many in Britain's ruling elites supported him - and this would have changed everything. With unchallenged command of Europe, Hitler would have been able to implement the full force of Nazi ideology.

Some historians have also argued that if the war had not continued, the Holocaust might not have happened. But genocide was the logic of Nazism. In the eyes of Nazis, racism was a science, claiming to show that some parts of humanity were inferior and fit only for extermination. There's no reason to think Hitler wouldn't have followed that logic to its terrible conclusion, and it's entirely realistic to think that the hideous world that Hitler aimed to create would have come fully into being and still exist today.

As Churchill said in a speech in the House of Commons in June 1940: "If we fail, then the whole world will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age, made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science."

Even if we don't think past events were bound to happen as they did, we tend to believe that the larger course of history is shaped by vast, impersonal forces. But for a couple of days in May 1940, the fate of the world turned on the fall of a leaf.

If Bracken hadn't left Australia to reinvent himself as an Englishman and appointed himself as Churchill's faithful protector; if Beaverbrook and Bracken hadn't found Churchill brooding in his club; if Bracken hadn't succeeded in persuading Churchill to remain silent; and if Churchill hadn't been prepared for the desperate struggle that followed by the visits of the black dog, history would have been very different and the world darker than anything we can easily imagine.