Last meal: What's the point of this death row ritual?

- Published

The state of Texas has ended the practice of offering death row inmates their choice of last meal before their deaths. What does a killer's choice of food say about his state of mind?

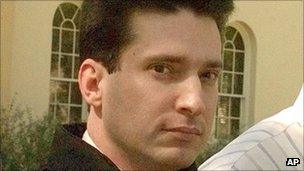

Lawrence Brewer's last request was so extravagant it seemed a mockery.

Just before the acknowledged white supremacist was put to death by lethal injection on Wednesday, he ordered two steaks, a triple-meat cheeseburger, a cheese omelette, a large bowl of fried okra, three fajitas, a pint of ice cream and a pound (0.45kg) of barbecue meat.

It's not clear how much of that he was actually served, or whether his nerves affected his appetite, but he ate none of it.

The following day, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice heeded the request from an outraged Texas state senator to end the tradition of the generous last meal.

From now on, condemned men in Texas will be offered the same cafeteria chow as other prisoners.

What men and women request for their last meal reflects how they lived their lives and how they choose to face their deaths, and offers Americans a poignant human connection to the people they have decided should die for their crimes, scholars and legal analysts say.

And as a ritual, the last meal is intended not to comfort the condemned but to soften for society the harsh fact that a human is about to be killed with the law's full sanction, says Jon Sheldon, a Virginia death penalty lawyer.

He has sat with three condemned men in the hours before their executions, including infamous Washington sniper John Allen Muhammad.

"I don't know anybody who has eaten the last meal," Mr Sheldon says.

"In my experience, it is unlikely that someone is going to be hungry and is going to want a meal. It's either not ordered, or it's ordered and it's not eaten."

Florida, which has executed 69 convicts since 1976, budgets $40 (£26) per inmate, and the last meal must be purchased locally.

Take-away meals

Oklahoma - 176 men and three women executed since 1915 - is more miserly, giving prisoners only $15 to spend on a last meal, subject to the warden's approval.

Brewer was executed for the murder of an African-American man dragged to death behind a truck

The meal has to be purchased from a restaurant within the town of McAlester, home to the death chamber, says Jerry Massie, a spokesman for the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

"The staff doesn't prepare it," he said.

The last man executed there ordered a deep dish meat lover's pizza from Pizza Hut, and deep fried shrimp with cocktail sauce and hushpuppies - fried cornmeal balls - from fast food outlet Long John Silver's, Mr Massie says.

The man before him had a large pepperoni and Italian sausage pizza and a large Dr Pepper soda.

A review of last meal requests in Texas between 1982 and 2003 shows the most popular requests were grilled or fried foods like burgers, fried chicken or steaks.

This suggests the condemned had sought a last sensual reminder of home before they died, says Phoebe Ellsworth, a professor of law and psychology at the University of Michigan.

"Most of the offenders come from fairly poor backgrounds," says Prof Ellsworth, who has researched capital punishment extensively.

"It's a memory of something about life on the outside. 'When we went out to have a good time, what did we have?'"

A significant number of inmates forgo the last meal, whether in defiance of the ritual or for lack of appetite. Or for spiritual reasons: David Clark, executed in Texas in 1992 at age 32 for a double murder, told prison officials he wanted to fast.

"They have other things on their minds," Mr Sheldon says. "Inmates have gotten tired of co-operating with these rituals of death."

Alcohol is prohibited, and requests for cigarettes and bubble gum have been turned down.

'Christian connotation'

The ritual of the last meal captures the public imagination because the activity of sitting down for dinner is one Americans with no experience of prison life can relate to, says Deborah Denno, a professor at Fordham University School of Law in New York and an expert on capital punishment law.

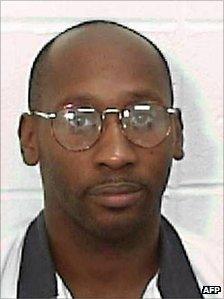

Troy Davis, executed on Wednesday in Georgia, declined a last meal

"It brings us back to the fact that this is a human being who will not be having any more dinners like we do," she says.

"There's a drama associated with it. This is the Last Supper. Maybe it has that Christian connotation."

In Texas, the state that has executed the most people in the country since modern capital punishment resumed in 1976, with 475, State Senator John Whitmire says his push to end the last meal tradition was made of moral concerns, not financial ones.

And he vehemently disagrees with critics who say it is petty and mean-spirited to withhold from the condemned one last creature comfort.

"If you're fixing to execute someone under the laws of the state because of the hideous crime that someone has committed, I'm not looking to comfort him," he says.

"He didn't give his victim any comfort or a choice of last meal," he says of Brewer.

Rather than reform the last meal, Texas officials should worry about the justice, efficacy and constitutionality of capital punishment there, says Richard Dieter, executive director of research organisation Death Penalty Information Center.

"They take it away, hopefully they're looking to what they should be providing. A last lawyer rather than a last meal is much more important."