Growing up a foreigner during Mao's Cultural Revolution

- Published

Paul Crook - back - was in school when the revolution began

Paul Crook's Communist parents met in China in 1940 and brought up their three sons in Beijing. In the 1960s, Paul was caught up in the Cultural Revolution, a chaotic attempt to root out elements seen as hostile to Communist rule.

"We were encouraged to write posters criticising our teachers and the school leaders for anything seen as being 'Revisionist'.

My classmates and I would get big sheets of paper, poster size, and write all sorts of things and put them up in the classrooms and hallways.

If sometimes the teachers were not very nice to you, then this would be a chance to get back at them.

At the beginning there wasn't really much violence in my school, on the whole it was civilised, supposedly fighting against wrong ideas, but no doubt very demeaning, even horrific for many teachers.

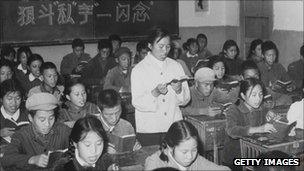

Red Guard high school students read from Mao's Little Red Book

I do remember one of the more unruly students picked on an art teacher who was said to come from quite a bourgeois background.

He was one of the best teachers, I really liked him.

We were in a room with him and one of the other students had a baseball bat and was about to hit him and one of my friends said, 'Hey you can't do this'.

On that particular occasion we avoided any violence.

But elsewhere, there was much violence, as the Cultural Revolution went on.

'Bourgeois authorities'

Mobilised by Chairman Mao, millions of young people became Red Guards.

They hounded anyone who they thought was sabotaging the Communist Revolution, many of them highly placed members of the Communist Party.

If you were noticed, a celebrity of any sort, you were fair game.

Academics, Party officials and others who were seen as being 'bourgeois authorities' were dragged off to meetings to be 'struggled against' in front of large crowds.

Many people were locked up - sometimes even killed or driven to suicide.

There was huge upheaval at the university where my parents, David and Isabel, worked.

At that time school students from the cities were regularly sent to work in the countryside during harvest season, and upon graduation many were sent to settle in the country, to share the life of the farmers.

In those days everyone in the countryside was a member of a 'People's Commune', working together, and sharing the proceeds.

In the autumn of 1967, I joined a bunch of foreign kids and went to a commune just outside Beijing, where we harvested sweet potatoes and pears.

It was a very happy time, but then when I came home three weeks later my brothers said, 'You'll never guess what has happened, they've arrested a spy at the university among the foreigners, can you guess who it is?'

I thought of a few relatively dodgy characters. But it turned out to be my father.

'Spy'

It was a bit of a joke because we thought, he believes in all this, supports the revolution, how could he be a spy?

We thought my father would be released within a few days, in a few weeks.

We had all been educated to think that things were getting better all the time, but sometimes there would be mistakes.

One of the slogans at that time was: 'You should trust the Masses, and trust the Party!'

As I recall, I don't think I seriously thought that my father would ever not be released and I did not think he would be abused physically, so we just went on living.

We were constantly going to different government departments to find out where he was locked up, so we could deliver reading material to him or food that he liked.

My mother was repeatedly summoned for questioning and eventually she too disappeared.

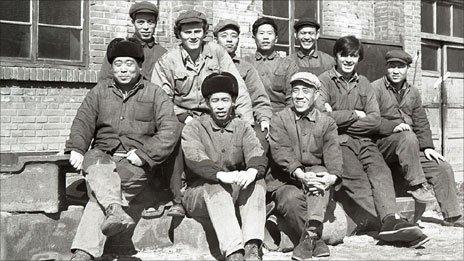

Paul Crook with fellow workers at farm implements factory

By then the university was run by a Revolutionary Committee supervised by the Workers' Propaganda Team, and by army representatives sent to take control of universities by Mao.

But my brothers and I continued to receive our parents' wages, and we were getting older, and were pretty well able to look after ourselves.

After I left school, I worked in a farm implements factory, and later an automobile repair plant.

We were anxious about what had happened to our parents, but we weren't eaten up by anger or worry, as we were brought up to believe that if you were innocent then this would be proved in due course.

Meanwhile my parents' friends gave us care and encouragement, and the official position towards young people whose parents were in trouble was that they could still be educated 'to take the right path'.

'The right path'

For a long time we thought it would just be a few months and we kept hearing things, rumours about the latest political twists and turns, and we thought - hoped - our parents would be coming out quite soon.

In the end my mother was freed after just over three years of lock-up on the university campus.

My father was released from prison after five years, much of it spent in solitary confinement.

He and my mother were later exonerated of any wrongdoing, and received an official apology.

My parents were never physically abused in all the time they were locked up, but it was a trying time, to say the least.

They were sustained by their belief that all this upheaval was part of an attempt to create a better society.

Although the time of my parents' incarceration was a period of turmoil in China, and we were concerned for our parents, it also was a time of independence for me and my brothers.

We had opportunities to travel around the country, and there was plenty of time for teenage fun, going out hiking in the hills, and parties and dancing in the Friendship Hotel, where foreign residents in Beijing lived a somewhat sheltered life.

Inevitably, what happened then shaped the way I saw the world.

Like many of my friends I grew to be rather sceptical, to be critical of what people's stated intentions were, and what their grand visions entailed.

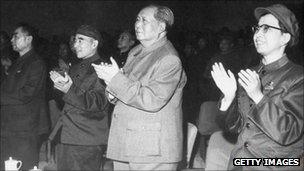

Chairman Mao actively courted the young

My father said when he was locked up, he did think it was a mistake and wondered how he could clear his name.

When he came out he found that many of his Chinese colleagues had gone through very similar experiences.

And he was reconciled to the fact that the leadership was making an earnest effort to get rid of these abuses.

He had lost five years of his life in prison but he didn't see why he should change his ideals.

He and my mother continued to work at the university for many years before retiring, teaching and writing about what was going on in China.

My father also worked on a Chinese-English dictionary, which is still in use today.

That is what they wanted to do, to give meaning to their life.

My father died in China, while my mother still lives there, leading an active life."

Paul Crook left China and came to the UK, where he worked at the BBC World Service for nearly 30 years. He told his story to the BBC World Service history programme, Witness.