Aboriginal Stonehenge: Stargazing in ancient Australia

- Published

An egg-shaped ring of standing stones in Australia could prove to be older than Britain's Stonehenge - and it may show that ancient Aboriginal cultures had a deep understanding of the movements of the stars.

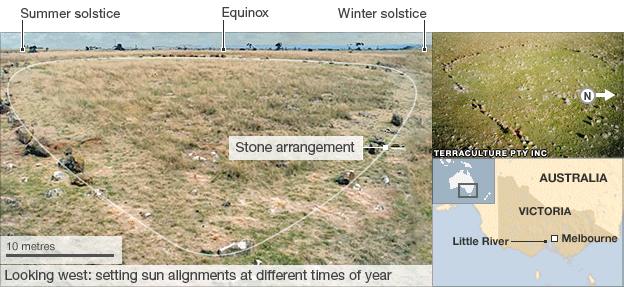

Fifty metres wide and containing more than 100 basalt boulders, the site of Wurdi Youang in Victoria was noted by European settlers two centuries ago, and charted by archaeologists in 1977, but only now is its purpose being rediscovered.

It is thought the site was built by the Wadda Wurrung people - the traditional inhabitants of the area. All understanding of the rocks' significance was lost, however, when traditional language and practices were banned at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Now a team of archaeologists, astronomers and Aboriginal advisers is reclaiming that knowledge.

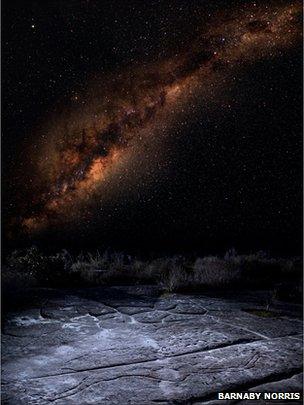

This photo of the emu in the sky, above an aboriginal rock carving, was sent to every school in Australia

They have discovered that waist-high boulders at the tip of the egg-shaped point along the ring to the position on the horizon where the sun sets at the summer and winter solstice - the longest and shortest day of the year.

The axis from top to bottom points towards the equinox - when the length of day equals night.

At Stonehenge, the sun aligns instead with gaps in the stones on these key dates in the solar calendar.

The probability that the layout of Wurdi Youang is a coincidence is minuscule, argues Ray Norris, a British astrophysicist at Australia's national science agency, who is leading the investigation.

Prof Norris and his Aboriginal partners used Nasa technology to measure the position of each rock in relation to the sun, and to demonstrate the connection with the solstices and equinox.

"It's truly special because a lot of people don't take account of Aboriginal science," says Reg Abrahams, an Aboriginal adviser working with Prof Norris.

As happened with Stonehenge, the discovery could change the way people view early societies. It is only recently that it has been demonstrated that Aboriginal societies could count beyond five or six.

Songs and stories

"This is the first time we have been able to show that, as well as being interested in the position of the sun, they were making astronomical measurements," says Prof Norris, who is also a faculty member at the School of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Other studies by Prof Norris, of Aboriginal songs and stories, have also indicated a clear understanding of the movements of the sun, moon and stars.

Indigenous customs vary among groups across Australia, but one story that appears in many local traditions is the tale of a great emu that sits in the sky.

The emu, which can be seen in the southern hemisphere during April and May, is a shape made by the dark patches of the Milky Way.

Its appearance coincides with the laying season of the wild emu and for the storytellers it is a sign to start collecting eggs.

Prompted by historian Hugh Cairns, Prof Norris examined and photographed an emu-shaped rock carving in Kuring-Gai Chase National Park, near Sydney, which cleverly mirrors the celestial animal-like shape.

During the southern autumn, the constellation is positioned above the rock with the bird shape almost perfectly reflected by the engraving.

Intellectual leap

Other stories show more complex, intellectual understanding of the universe.

In the case of the solar eclipse, the Walpiri people in the Northern Territory tell the story of a sun-woman who pursues a moon-man. When she catches him the two become husband and wife together causing a solar eclipse.

The idea that the solar eclipse is caused by the moon moving in front of the sun is something only widely accepted by western scientists in the 16th Century.

"This is not about balls of flames going out, it's about one body moving in front of the other," says Prof Norris. "That is a giant intellectual leap."

Since solar eclipses are rare, the survival of this story, passed down through generations, also shows a remarkable continuity of learning.

These discoveries play a crucial role in helping Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians understand just how intellectually advanced their ancient society was.

"This discovery has huge significance for understanding the amazing ability of this culture that is maligned," says Janet Mooney, head of Indigenous Australian Studies at Sydney University.

"It makes not only me, as an Aboriginal person, but a lot of Aboriginal people around Australia very proud."

She hopes to be able to tell her students of an aboriginal site more ancient than Stonehenge.

Until it is dated however, Wurdi Youang could be anywhere from 200 to 20,000 years old.

Aboriginal stone structures in the region have a vast age range and are very difficult to date. Many of the smaller rock sites that have been found, such as shelters and cooking areas, have been moved over time by natural and human forces.

But given the size of the stones at Wurdi Youang and how deeply they are entrenched in the ground it is more likely they have been there for thousands of years, archaeologists say.

Dating requires archaeologists to test the soil under the rocks to see when it was last exposed to sunlight and the team hope to be able to do this in the next few months.

But Prof Norris believes he has already proven the real value of the stone circle.

"It is interesting to know how far back people were doing astronomy, if it is 5,000 years old it would predate Stonehenge," he says.

"But it is not quite as interesting to my mind as whether the Aboriginal people were doing real astronomy before British contact. That really tells us a lot about what kind of culture it is."

Reach for the Stars - Aboriginal Astronomy was produced by Robert Cockburn and broadcast by Discovery for BBC World Service. Listen to the radio documentary via iplayer or download, external the podcast.