A decade on for the 'American Taliban'

- Published

John Lindh's father wants presidential clemency for his son

The television images of the bedraggled and bewildered young American detained in Afghanistan months after 9/11 were beamed across the world. They were seared into the consciousness of the country which quickly came to know him as the "American Taliban".

On a quiet suburban street in Mill Valley, a prosperous town a few miles north of San Francisco, the Islamic Centre is slowly emptying after holding Friday prayers.

Once the crowds have gone, Abdullah Nana recounts how over a decade ago a white teenager turned up, confused and looking for answers.

"He was at a crossroads at that time. He was unsure of his direction in this world. It seemed that Islam and religion was a way for him to spiritually fulfil himself."

Mr Nana says he quickly became friends with the 16-year-old, who converted to Islam and soon set himself the daunting task of learning Arabic and memorising the Koran.

That boy was John Lindh, also known as John Walker Lindh, who grew up in a middle-class Catholic family, and is now a prisoner in the "special communications unit" in Terre Haute, Indiana, halfway through a 20-year sentence.

His family argue that it is time to look again at the case of "Detainee 001", the first terror suspect picked up in the "war on terror" which President Bush declared 10 years ago.

According to his father Frank, he is housed in a special wing at the west end of the building which had originally been used as death row.

It is here that Lindh, who is enrolled on a correspondence course with Indiana University, has completed the task of memorising the Koran.

Adventure

At the age of 17 he had got his parents' permission to travel to Yemen to study Arabic. He briefly returned to California but couldn't settle so he headed back to Yemen from where he wrote to ask his father if he could go to Pakistan to continue his studies.

Frank Lindh replied: "I trust your judgment and hope you have a wonderful adventure."

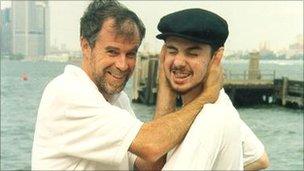

Father and son on family holiday in New York

Once there, Lindh enrolled at a religious school in the village of Bannu in the North West Frontier Province where it seems his views hardened.

Without his parents knowing, in June 2001 he slipped over the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan.

Once there, with the assistance of a militant group, he received two months of military training at the al-Farouq training camp which was financed by Osama Bin Laden.

Twice that summer he met the al-Qaeda leader but Frank Lindh denies his son had anything to do with terrorism, claiming he "was one of thousands of young Muslims who over the years volunteered their services in Afghanistan against the Russian-backed warlords" of the Northern Alliance.

But Michael Chertoff, who was assistant attorney general at the time, says Lindh "went to fight for a regime that was hostile to the United States and that supported the 9/11 attacks.

So in my book, that's pretty serious.

It's not quite treason but it's what I would call a kissing cousin to treason".

Pivotal moment

The original indictment against him shows that Lindh was approached by al-Qaeda to carry out an attack in the United States or Israel but he refused.

Marilyn Walker, Lindh's mother, fears for the future her son might endure when released

By early September he was serving in a corps of 75 non-Afghan soldiers in the Takhar region of north-eastern Afghanistan.

It was then that everything changed, according to Frank Lindh.

"There was a pivotal moment in history. 9/11 occurred and then the American government made a decision to change our policy very abruptly and invade Afghanistan and topple the Taliban government."

Shortly after the aerial bombardment of the country began, Lindh's unit was forced to retreat, walking through the desert to Kunduz where they surrendered to the Northern Alliance.

They were transported to the Qala-i-Jangi fortress on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif which was under the control of the warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum.

When a battle erupted within the fortress, a CIA officer and hundreds of prisoners were killed. Lindh was shot in the leg.

For the following week, he and other survivors huddled in a basement.

He claims that Dostum's forces lobbed grenades down air ducts, killing more prisoners, and then pumped in freezing water to try to drown them.

With shrapnel wounds and hypothermia, Lindh managed to get above ground and on 1 December 2001 was handed over to US custody.

Anger

It was then, after hearing nothing for seven months and growing increasingly frantic, that Lindh's parents discovered what had happened to him.

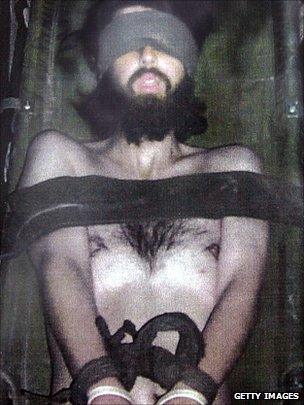

They saw an online news article which contained a grainy photograph of what they immediately recognised was their son.

Lindh, after his capture, photographed by a US soldier

Frank Lindh is angry about what happened next. His son was flown to a marine base at Camp Rhino where he claims they "left him in an unheated metal shipping container completely naked for two days and two nights in the desert in Afghanistan" with his "wounds untreated".

There then began what Lindh's mother, Marilyn Walker, describes as an unstoppable "tidal wave" of negative media coverage.

Attorney General John Ashcroft announced that Lindh was "an al-Qaeda-trained terrorist who conspired with the Taliban to kill his fellow citizens".

"That image was sealed in the minds of people when they were emotionally distraught and in grief after 9/11," says Frank Lindh.

It was into this atmosphere in January 2002 that Lindh was flown back to the United States, but in a last-minute plea bargain the authorities dropped the terrorism and al-Qaeda charges in return for Lindh pleading guilty to supporting the Taliban and dropping his claims of mistreatment.

Appearing in court, John Lindh acknowledged: "I made a mistake by joining the Taliban… I want the American people to know that had I realised then what I know now about the Taliban, I would never have joined them."

Wrong place

The 20-year sentence was, according to his father, the best he could hope for since "the well was poisoned against my son in the United States".

Michael Chertoff defends the outcome. "He pleaded guilty, the judge imposed what seemed an appropriate sentence and I assume he'll serve it out."

Reacting to the claim that Lindh was in the wrong place at the wrong time, Mr Chertoff says: "The prisons are full of people who say they were in the wrong place at the wrong time."

So the visits continue to Terre Haute where, separated by glass, Lindh speaks to his family over a telephone which is monitored.

Lindh never shows a sign of self-pity, his father says, and never complains, but had once told him that this was a deliberate tactic.

"He feels that complaining would yield something to the authorities who are imprisoning him," says Frank Lindh.

Lindh's parents try to chip away at what they see as a false public image of the "American Taliban".

Marilyn Walker says: "It's critical for John's life at whatever point he gets out of prison that he is able to live without having to look over his shoulder for someone that wants to do him harm".

Though his parents hope the president will one day grant clemency to allow an early release, they recognise the prospect is unlikely.