Mallory and Irvine: Should we solve Everest's mystery?

- Published

- comments

The mystery of whether two British adventurers were the first to reach Everest's summit has long intrigued the public. But do we really want to know the truth?

As a tale of doomed, romantic endeavour, it has endured for decades.

It is also Everest's most persistent mystery - did George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine make it to the top in 1924, almost 30 years before it was officially conquered?

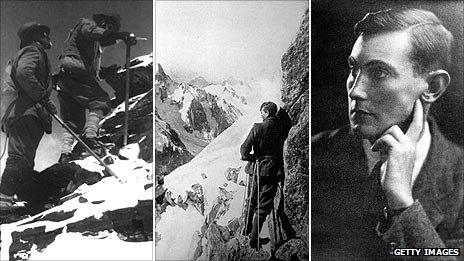

The pair, equipped with primitive climbing gear, were last sighted a few hundred metres away from the summit before bad weather closed in around them.

Wearing Burberry gabardine jackets and hobnail boots, and carrying a rudimentary oxygen supply, their gear was a far cry from the hi-tech protective clothing worn by modern mountaineers.

Everest gripped the imagination in the 1920s

And historians have long argued whether or not they made it to the peak before succumbing to the freezing conditions.

A forthcoming expedition to Everest aiming to establish what exactly happened is just the latest in a series of attempts to solve the puzzle. But despite the continued speculation, many of those with a stake in the mystery hope it will never be resolved, fearing the prosaic truth could never match the legend.

Successive expeditions have been staged to try to piece together their movements. The discovery of Mallory's body in 1999 fuelled interest in the mystery but failed to resolve it.

Those who believe the duo did reach the summit believe a camera carried by them could finally settle the controversy. If the two men did reach the top, it is reasoned, they would have taken a photograph.

When Mallory's remains were found, no camera was recovered. Now the new US-led hunt in December will seek Irvine's body and the missing film.

Julie Summers, Irvine's great-niece and biographer, who is undertaking a lecture tour about him, is one of those who hopes the mountain will retain its secret.

"I like the idea of it being one of our great enduring mysteries," she says.

"There's something about the romance of it - there's an otherworldliness to the story."

Certainly, few would doubt that the tale of Mallory and Irvine has come to represent more than just a single, doomed climb.

The persistence of the story has much to do with its protagonists' contemporary fame. The attempt to conquer Everest was closely followed by the public and the subject of regular breathless dispatches in the Times prior to their disappearance.

But the historical context ensured their disappearance symbolised more than simply the tragic deaths of two young men. The recent memory of World War I - in which most of the expeditionists, with the notable exception of 22-year-old Irvine, had served - added an additional dimension of poignancy to their loss.

Subsequently, too, the noble failure of this ill-equipped, Boys' Own-like adventure has come to be seen as a symbolic portent of the British empire's demise.

The personal dynamic of the pair has added much to their continued mystique.

Mallory was an aesthete and Cambridge lecturer who had consorted with members of the avant-garde Bloomsbury Group. In one of the most famous statements ever made about mountaineering, when asked why he wanted to climb Everest, Mallory replied: "Because it's there."

Irvine, 15 years his junior, was a taciturn engineering student whose physical strength and uncomplaining hard work meant he was chosen by Mallory to be his companion during the ascent, despite the younger man being the least experienced climber in the 13-strong expedition team.

The tragedy of two individuals - one consumed by a desire to overcome the summit, the other bolstered by youthful fearlessness - driving themselves on towards their fate is what makes the story compelling, believes Rebecca Stephens, the first British woman to climb Everest.

"If you have that burning desire inside to do something like that, it's very difficult to let go," she says.

"With Mallory, there's no question that climbing Everest was everything to him. Irvine was so young, I think he just got carried along."

Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay are recorded as the first to make it

And while this compelling personal narrative leads some to protect the myth, it also inspires among others a drive to attempt to find out exactly what happened to them.

Film-maker Graham Hoyland was part of the 1999 expedition which found Mallory's body and has written a book which, he says, will settle the mystery.

Hoyland says he recognises the saga's allure. But he believes that uncovering the men's fate is the only way to truly appreciate their achievements.

"I think we should historicise it rather than mythologise it," he says.

"I do understand the appeal of the myth - as a boy I was besotted by the story. But I do think there's more value in getting the truth out. That's the only way we can really assess the circumstances."

Whether these two remarkable men reached the summit may never be resolved. But whatever the outcome of the next expedition, the fascination their story inspires is unlikely to fade.