A Point of View: Prisons don't work

- Published

- comments

Prison does not work for the majority of inmates either as punishment or rehabilitation, writes Will Self.

If you stand on a main road in a British city and wait for long enough several kinds of vehicle will pass you by.

Naturally, there will be the relentless snort and grumble of cars and lorries, the snarl of motorcycles and the hiss of buses. But also with unflagging regularity nowadays there comes the demented wail of police cars, ambulances and fire engines weaving through the stalled traffic.

However, there's another kind of vehicle that may well escape your attention: boxy, four-square vans of the sort used by security companies to transport cash and other valuables, but painted white and with anything from two to eight opaque windows ranged along their hard riveted hides.

Next time you see one of these distinctive vans stopped by a traffic light, why not go up close to the windows, wave, and mouth the words of a silent greeting because inside, unseen yet able to view a tinted world, will be sitting a human being just like you, but in all probability shackled.

In prison slang these vans are known as "sweat-boxes" because the tiny individual cells they house, which are furnished with unpadded plastic seats, can grow intolerably hot.

The occupants of the sweat-boxes may be being transferred from prisons to courts, or taken on some other more or less rational journey mandated by their confinement.

However, often they will simply be being "ghosted", another apt slang term that perfectly captures the condition of inmates shifted from one prison to another, without warning, on a senseless go-round seemingly designed to disorientate and pacify.

It was Dostoevsky who said: "The degree of civilisation in a society is revealed by entering its prisons." But in contemporary Britain you don't even need to do this, you can simply stand on a street corner and wait for the ghosts to come flitting past in order to appreciate its parlous condition.

We now have the highest prison population in Europe by a considerable measure, and following the recent riots there is no likelihood of it decreasing.

Of course, we aren't quite at the levels enjoyed by our closest allies, those prime exponents of the civilising mission the United States, whose extensive gulag now houses, it is estimated, more African American men than were enslaved immediately prior to their Civil War - but we're getting there.

Powder keg

Then again, should you have cause to actually enter one of Her Majesty's prisons - as I have on many occasions as a prison visitor - you'll be in a position to appreciate the extent to which it is a decoction of modern urban Britain, what with its high numbers of ethnic minorities, alcoholics, drug addicts and the mentally ill.

Like society at large, I've discovered that prisons are beset by endless rules administered by petty-minded, management-speak-spouting bureaucrats - rules, programmes and so-called initiatives that result in the wastage of taxpayers' money.

Also in common with the wider world, prisons are benighted by an almost breathtaking hypocrisy. In their case this is summed up by the stentorian signs by the barred gates warning visitors about to be searched that the penalties for attempting to smuggle in contraband items such as drugs, weapons, mobile phones take the form of yet more custodial sentences.

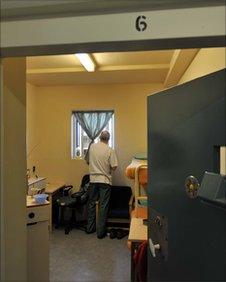

Prisoners can spend a lot of time confined to their cell

It's breathtaking hypocrisy because the very prison officers who frisk you just might be trafficking the drugs with which the system is awash. Time and again addict inmates I've spoken to have told me that it's easier to obtain heroin in jail than out.

Contrary to the view of prison as a deterrent and a way of keeping criminals off the streets, almost all enlightened opinion now concurs in the following.

Not only does prison, for the vast majority of those who endure it, not work, either as punishment or as rehabilitation, but there is no escaping the conclusion that it functions as a stimulant to crime, rather than its bromide.

The current chief inspector of prisons for England and Wales recently warned that the latest pupils to enrol in these £30,000 per-annum malefaction academies are being recruited by criminal gangs, and will almost certainly reoffend upon their release - if not before.

And yet what political will there is to deal with the problem when in opposition, and it's often considerable, drains away once the reins of power are taken up. The current government is only the latest whose stated determination to sluice down the Augean stables of Wandsworth, Strangeways and Parkhurst has resulted in an ineffectual piddle. The question is, who's treading on the hose?

Certainly there is the dead weight of the prison bureaucracy, a Kafkaesque interleaving of public service boondoggling and private sector lobbying, whose raison d'etre is not the reduction of the prison population but its increase.

Then there are the ministers who, by definition strangers to the seamier side of life, find themselves on inspection visits, face-to-face with scary inmates either hopped-up on illegal drugs, or zombified by prescribed ones. And who are told by heavy-set, authoritative men and women that this is a powder keg only prevented from going off by the sheer weight of their boots.

Class layer-cake

But a far more important choke on reform is that a significant portion of the great British public, already infuriated by the sums spent on prisoners, bitterly resent the notion of spending still more.

They are right. Much more spending would be required to effectively separate sheep capable of being herded in the right direction from goats that simply have to be confined.

Much more money would also be needed to put in place comprehensive drug and alcohol treatment programmes that actually work. And still more cash would be necessary to treat mentally ill prisoners, teach illiterate prisoners and make unskilled prisoners employable.

Whatever cost-benefit analyses are presented to them, the public, or at least that vocal section of it whose cries for law and order make penal reform electoral suicide, resent this expenditure.

But anyway, it appears they don't really want prisoners rehabilitated, they want them punished. They want them locked down, maltreated and if it were possible beaten on a regular basis.

The public have different perceptions of what prison is like

They require convicted prisoners to be scapegoats for all that is wrong with society, while paradoxically desiring them to pay their debt to it, as if spending 23-hours a day in a cell watching television could possibly equate with turning up for work, paying taxes and otherwise doing your bit. These people erroneously believe that punishment works and point to the happily virtuous past to prove it.

Certainly, if we go back a hundred years we find remarkably law-abiding citizenry and only 15,000 or so in prison as against today's ninety-odd, but perhaps this was because society for the lower orders, as they were then dubbed, was already a form of imprisonment?

There was little opportunity or energy to commit crimes when you were already doing hard labour for six-and-a-half days a week, nor was there any need for additional confinement when so much of the workforce was already banged-up below stairs.

The sort of nostalgia that attaches itself to the serialised class layer-cake that is Downton Abbey is of a piece with the refusal to recognise that grotesque inherited privilege is something people have struggled hard to do away with. Not without accident are our prison cess-pits nominally possessed by the Queen.

I'm not such a bleeding-heart liberal that I don't recognise the need for imprisonment when someone has been convicted of a violent crime, but unless an individual represents a credible physical threat I'd far rather he was set to work in the community to pay back what he has taken.

In those cases where redistributive justice is impossible because the offender is already so socially inutile, their rehabilitation must consist precisely in assisting them to be the responsible citizen they have heretofore failed to become.

The raw meting out of punishment solves nothing. And although there are some psychopaths who may have to be confined indefinitely, the Manichaean belief in the unbridgeable rift between sanctity and evil that shadows so much of our thinking about prison should play no part in its actual administration, any more than should a belief in ghosts.