Tax havens: Is the tide turning?

- Published

- comments

The Cayman Islands offer a wide range of financial services

Around the world, grassroots opposition to tax avoidance is on the rise. But a survey shows that all but two of the UK's biggest 100 companies have subsidiaries in tax havens, from the Cayman Islands to Singapore. So is big business out of step with public opinion?

Occupy Wall Street protesters demand corporations "pay their fair share" of tax. U2 comes under fire from protesters at the Glastonbury festival who accuse the band of taking advantage of low tax rates in the Netherlands. A global day of action against tax secrecy is marked in dozens of countries from Ghana to Brazil.

Protesters stage sit-ins in shops and banks around the UK in the hope of getting tax avoidance by massive corporations on to the political agenda.

U2 have been criticised for moving their tax affairs to the Netherlands

In recent months, a loose coalition on "tax fairness" has emerged, uniting angry taxpayers, business ethics pressure groups and development NGOs. The focus is now on tax avoidance - legal arrangements to pay less tax, sometimes using complicated financial structures - rather than just illegal tax evasion.

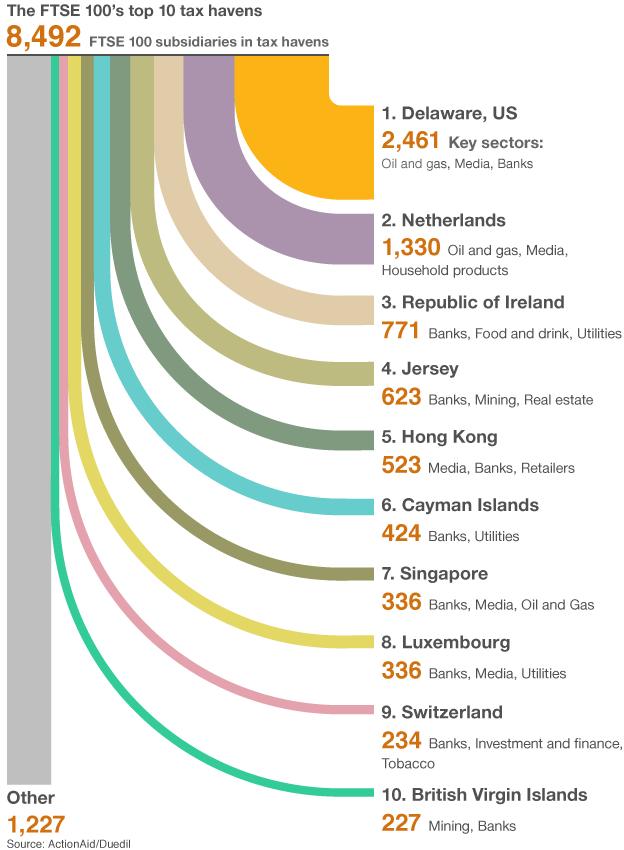

One of the campaigning groups, charity ActionAid, has just released data, external that shows, it says, the "addiction" of the FTSE 100 - the UK's most valuable companies - to tax havens.

The data should have been publicly available, ActionAid says, but in many cases wasn't - the charity obtained it by filing complaints to Companies House. Then it counted how many subsidiaries each of the 100 companies has, and the proportion of them that are located in a tax haven.

The headline results are:

Of the FTSE 100's 34,216 subsidiaries, about a quarter - 8,492 - are in tax havens

Only two companies - financial advisers Hargreave Lansdowne and Mexican mining company Fresnillo plc - have no subsidiaries in tax havens

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) says four factors are used to determine whether a jurisdiction is a tax haven. A place can be considered a tax haven if it imposes no or only nominal taxes, if there's a lack of transparency, if there are laws that prevent the effective exchange of information with other governments and if it is trying to attract investment and transactions that are purely tax driven.

But there is no generally agreed definition of "tax haven".

For its survey, ActionAid took a list used by the US Congress and added two further jurisdictions - the US state of Delaware and the Netherlands. Some consider countries to be tax havens if - like the Republic of Ireland and the Netherlands - the way they tax cross-border income allows companies to shift profits to genuine tax havens, Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, for example, where they avoid tax altogether.

Delaware doesn't make company accounts public, and allows owners of companies to hide their identities.

ActionAid is not accusing the companies of illegal tax evasion. It acknowledges that there is not even any proof of legal tax avoidance, just a strong whiff of it.

"In most cases the huge number of subsidiaries in a given location does not reflect the actual level of business carried out. This suggests another motive for their choice," the charity says. But a whiff may be enough, in the current climate, to harm a company's reputation.

The phrase "tax haven" itself has become a dirty word, says Peter Truesdale, associate director of business advisory firm, Corporate Citizenship.

"And that is because there is a clean word, that people understand - 'transparency'. If your affairs are not transparent, why should I trust you? People think someone has something to hide."

A recent report by Mr Truesdale and two other Corporate Citizenship staff, external notes: "The distinction between evasion (illegal) and avoidance (lawful) has dissolved in the eyes of governments, NGOs and citizens."

Increasingly, people are demanding not just that a company's tax affairs are legal, but that they are "fair".

This is a very difficult thing to define, notes a London tax specialist at a large financial services firm, who asked to remain anonymous.

"There is a debate to be had about what proper amount of tax to pay to a particular jurisdiction. One person's perception may be very different from another's."

When directors take such decisions, he goes on, they have to bear in mind their duty to increase profits and increase value for shareholders.

But while "tax efficiency" is important, it is now rare to find companies that do not also consider how their actions will be judged in the increasingly harsh court of public opinion.

A company could look to a low-tax country to avoid extra bills when moving money around the world

"The public debate tends to be black and white, emotive and headline-grabbing," he says. "In reality it's a much more complicated problem.

From the business perspective, it can sometimes seem it is the public debate about tax that is unfair.

A company like Vodafone might point out it has businesses in 30 countries, and paid £2.6bn in corporate tax worldwide in the last financial year. Vodafone says the UK is only a small bit of the overall group, and that it effectively gives £700m to the Exchequer every year in VAT, employee taxes and national insurance.

Richard Baron, head of taxation at the UK-based Institute of Directors, says there is no doubt that there are some very complicated avoidance schemes that use tax havens but people should not always impute a "dodgy reason".

For example, a firm may have a number of businesses in Africa but it wants to group all of them under a single holding company.

"You want to make sure you don't get an extra layer of tax when the profits flow up. For that reason you may put a holding company in a low tax country and you may choose that country because it has strong corporate governance and you want to know your money is safe."

Companies also do it when they need to create a "group treasury operation" so money can flow between their different parts all around the world.

"That operation does not belong to any particular country so you put it in a low tax country as you don't want to suffer an extra bill as you move money around."

Advertising giant WPP topped ActionAid's table with 611 subsidiaries registered in places widely regarded as tax havens. But a spokesman says WPP is a holding company for 150 brands which operate in 107 countries, some of which have a lower tax rate than the UK.

"We have come top of the table because of the international spread of our business and multi-brand business model and not because of any tax initiative," he added.

David McNair, senior economic justice adviser at the charity Christian Aid, says tax havens are used in a variety of ways, but the general principle - for a business active in a number of countries - is to maximise the amount of profit made by subsidiaries based where taxes are low, at the expense of those based where taxes are high.

This can be done by inflating or deflating prices, when the different parts of the business trade between themselves. Alternatively, one part can lend to another at a high interest rate (and profit from tax deductions on the interest payments at the same time).

There are rules - known as transfer pricing rules - which govern the prices that can be charged between companies in the same group but McNair says they are notoriously hard to apply, particularly for developing countries.

"Transfer pricing rules enshrine the 'arm's length principle'. The problem is determination of what is an arm's length price for, say, intellectual property, management services, or interest rates on an intra-company loan - where there is no open market and no comparable price to determine if the arm's length principle has been applied."

Christian Aid's concern, like ActionAid's, is that the biggest losers are developing countries, which often lack the expertise and the capacity to prevent companies exploiting tax loopholes, and when tax havens are involved their secrecy means they lack the most basic information.

ActionAid cites an estimate mentioned by the secretary general of the OECD, Angel Gurria, that developing countries lost almost three times as much to tax havens each year as they receive in aid.

Christian Aid was one of the organisers of the global day of action, on Friday, aimed at persuading the G20 to put tax secrecy on the agenda for its summit in Cannes next month.

The G20 summit in April 2009 ended with leaders declaring their intention to take action against tax havens but campaigners argue that the efforts since then to increase transparency have in practice had little effect.

According to McNair, public concerns about tax secrecy and tax fairness can be traced partly back to this summit. The recession has done the rest.

"We are facing austerity, governments are cutting basic services," he says. "If companies are getting away with escaping tax, this may be legal but it's unfair."