Meeting the king of simmering Bahrain

- Published

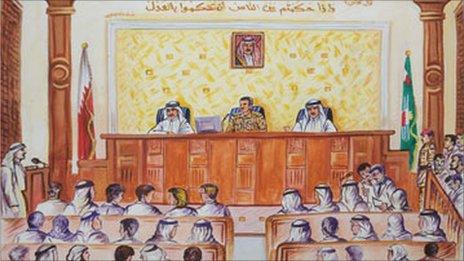

Dr Hajji is one of 20 medics convicted of incitement - she denies the charges

For a while earlier this year, protesters tried to bring the Arab Spring to Bahrain. They failed. The police cleared the streets, making many arrests, and reports of torture in custody have been rife.

In a white-walled village where the sun made me squint, I went to see a doctor.

Fatima Hajji is petite and elegant, her headscarf framing her face, her eyes shining beneath plucked eyebrows.

"Please," she gestured, "have a chocolate, while I just put my son to sleep."

Like several others in her profession, she stands accused of abandoning her ethics and joining the uprising earlier this year.

She said she did not, the prosecutors say she did, but I was more concerned with her treatment in custody.

Looking me in the eye while choking back tears, she described how a female interrogator had beaten her with a hose, electrocuted her then threatened to have her son abducted if she did not confess her crimes. She signed the papers.

This, and thousands of other alleged human rights abuses, are dragging Bahrain's name back into the Middle Ages.

A country fostered by the British, with supposedly the most advanced judicial and educational system in the Gulf, has gained a toxic reputation.

The king, a genial Anglophile who went to Sandhurst, is appalled and slightly baffled by events.

But he does not necessarily hold all the reins of power. A hard-core clique within the government wants little or no concessions to the protesters.

They, in turn, are having to fend off an even harder Sunni faction that wants maximum penalties for troublesome Shia demonstrators. They label them "khaa'in" - traitors - accusing them of having more loyalty to Iran than to Bahrain.

So when the invitation came to watch the state opening of parliament last week, it seemed a good opportunity to go and meet the people who run this island kingdom.

At the entrance gate I witnessed a tiny power struggle, a microcosm of bigger things afoot.

An army captain was refusing to allow our vehicle in.

A man from the king's court waved our gilt-edged invitation in his face, insisting we could come in.

While the stand-off continued I watched a policeman standing in the shade of a date palm, fidgeting with his sub-machinegun.

He studied the trigger mechanism as if seeing it for the first time, waving the weapon around disconcertingly, pointing it at trees, at cars, at us, then eventually at his own feet. It was rather a relief to drive past him.

Through a metal detector and into a large hall, I took in the scene.

Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifah has ruled Bahrain since 2002

Robed sheikhs with trimmed beards and cloaks edged with gold thread were giving each other elaborate greetings, the men touching their noses to each other in the tribal tradition.

There were clerics in white turbans, Western ambassadors in suits, police and army generals in full ceremonial dress, soldiers with berets and florid, Saddam-style moustaches, and women both veiled and unveiled.

Suddenly a courtier was at my elbow: "Mr Frank, his majesty would like to greet you."

After my last report on Bahrain's troubles which was less than flattering, this came as a surprise - but I rolled up with the rest of them, shorter than the King now that I am in a wheelchair.

The monarch smiled and held my hand, recalling when I had lived in his country in happier times.

I passed down the line to the prime minister, a man who has held that job uninterrupted for 40 years, coming to power when Britain still used shillings and pennies.

I looked at his tired features, remembering that this was the man whose removal the protesters had demanded unsuccessfully, back in March.

"We met before," I began.

"I know," he cut me short, "it was in the hotel lobby three years ago."

That sort of memory, I thought, is scary.

Cat and mouse

The next night I got my wish, to ride with the riot police and see how this controversial force does its job.

The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights says about 40 people have died since the unrest began in February

While they are not the ones accused of the sort of abuses alleged by Dr Fatima, there are countless stories from earlier in the year - some exaggerated, some true - of them smashing their way into houses, beating and dragging activists off to undisclosed police cells.

Tonight they were at pains to point out their respect for human rights.

"We give them warnings with loudspeakers to disperse," says a police captain.

"Then we use tear gas, rubber bullets and sound bombs. But they have weapons too: gas canisters, slingshots and steel spikes," he says.

As we drew up at a back street in a restive Shia village I could see the rubble of hurled rocks in the road while the tang of tear gas hung in the air.

Down the road a gaggle of young protesters waved a Bahraini flag and shouted slogans.

"They will go home soon," says the captain. "It's a school night and they have homework."

Sure enough, the youths dispersed, the police went back to their barracks.

It seemed almost like a game of cat and mouse but it left me with the disturbing feeling that Bahrain's simmering rebellion, by no means shared by all the country, is marking time, waiting for the moment when it will boil over once again.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 1130.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 1100 (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.

- Published5 October 2011

- Published29 September 2011

- Published21 August 2023